Before becoming a lawyer I assumed that arbitration was a lesser man’s litigation, an academic exercise kept behind the curtains. I was wrong. After a decade practising international arbitration, I’ve learned that no two arbitrations are the same; each requires its own thorough and creative approach to the intellectual aspects of the case, balanced with a cultural perspective that accounts for differences in legal backgrounds, business norms, and language barriers. If you’re looking to blend trial advocacy skills with the ability to navigate cross-border sensitivities, the practice of international arbitration can be highly rewarding.

Many of the same skills required of good commercial litigators are essential in arbitration. Advocates must exude confidence without it spilling into cockiness, and demonstrate a deep understanding of complex legal and factual issues that include knowledge of the client’s business and the opponent’s perspective. They must be able to reason, write, and speak with precision and spontaneity. They should also have composure, and communicate well with the client, opposing counsel, and the court/arbitration panel, tailoring the message to the audience and occasion.

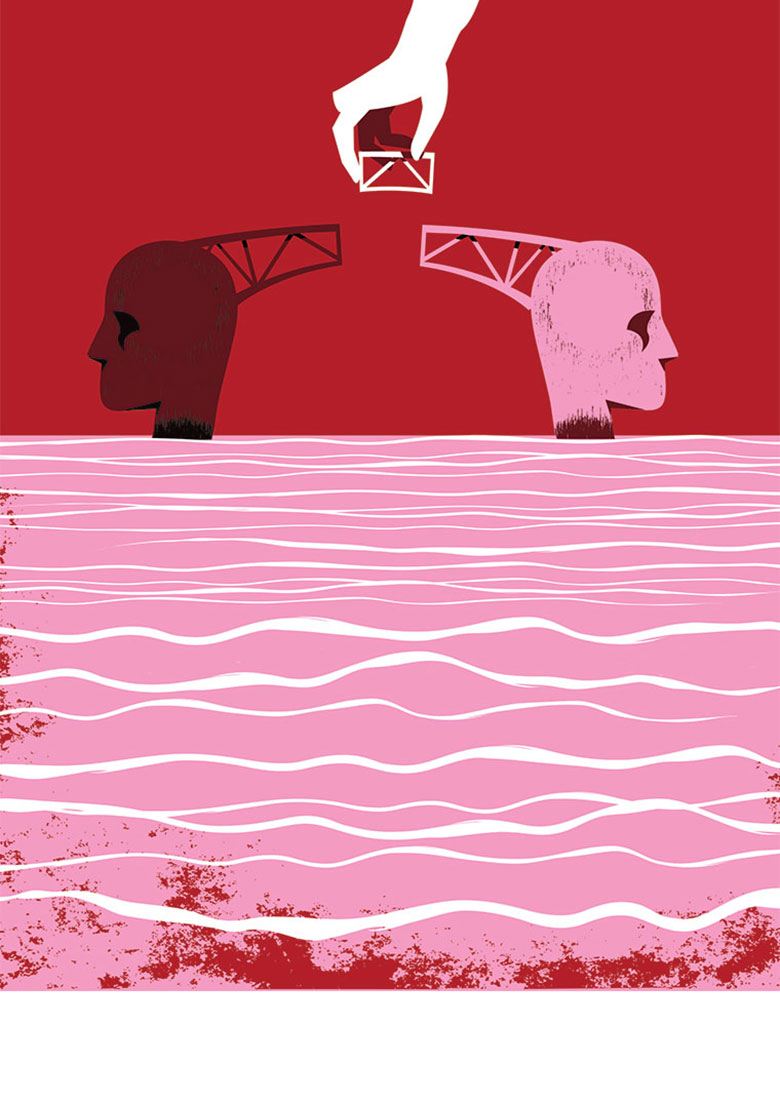

Good advocacy in international arbitration does not stop with hard skills, however. Cross-border sensitivity and respect for the cultures of the client, arbitrators, and opposing counsel plays a key role. An arbitration panel will often consist of jurists who do not hail from one’s home jurisdiction, do not share the same legal training or mother tongue, and may not share the same national background, business perspective, or worldview. Also, arbitrators, clients, and opposing counsel may be scattered across time zones.

All of this must be managed over the life of an arbitration. In particular, counsel must manage the presentation of evidence in light of the composition of an arbitral panel. Civil law arbitrators, for instance, may be less open than their common law counterparts to any cross-examination that borders on hostile. So not only the type of questions asked at a hearing, but also the tone and delivery, can make a material difference in the presentation of evidence.

Seemingly insignificant details can matter too. Familiarity with a national holiday can affect when to agree to an important conference call or other date with the arbitrators, or when to have draft witness statements for the client’s review. As another example, some business cultures hold an especially deferential view of the client decision-maker (such as a CEO). From the advocate’s perspective, sometimes a case can get paralysed unless there is a workable communication line established with the decision-maker to agree on everything from when to consent to a proposed hearing date, to whether to settle the case. This makes cooperation with supportive local counsel, or local offices, essential in ensuring the right client strategy throughout the case. It is also important to identify an interpreter with familiarity not just with the client’s general language, but a distinct dialect – such as mainland Chinese Mandarin versus Mandarin spoken in Taiwan. This can be crucial to precision of client testimony, as well as the client’s comfort level in giving it. The related decision of whether the interpretation should be done simultaneously, or consecutively, also deserves careful thinking. Where the language of the arbitration is foreign to the client witnesses, as is often the case, the mode of interpretation should be addressed with the client as early as possible in the proceeding to minimise the risk of a pre-hearing debate between lawyers about who should interpret and how.

Practising international arbitration is not without difficulty or frustration. The process is not always efficient, and the arbitrators, even reputable ones, are not always as astute in handling a case as one would presume them to be. But drawbacks aside, there has always been a higher level of gratification – for me – in experiencing a dispute being resolved between parties from different countries by a neutral, informed, decision-maker based on the specific process chosen by the parties.

This gratification is also more than theoretical – it plays out on a practical, day-to-day level. Whereas US ‘civil’ litigation can be a misnomer, the opposite is often true in international arbitration cases, especially those in which each party has seasoned advocates who understand the dispute is between clients, not lawyers. International arbitrations are governed by their own self-contained schedule, and procedural rules, which give a case a clear path to a final resolution. This has a real benefit to a lawyer trying to manage a busy practice, including those – like me – who juggle the testing demands of life in the office with those at home.

For the avoidance of doubt: International arbitration is not simply a ‘soft form’ of litigation. It is not for everyone, litigators who yearn for the rough and tumble of the local courtroom are not necessarily the best fit for international arbitrations but it can be a rewarding practice for those who appreciate old-fashioned advocacy carried out with a global perspective.