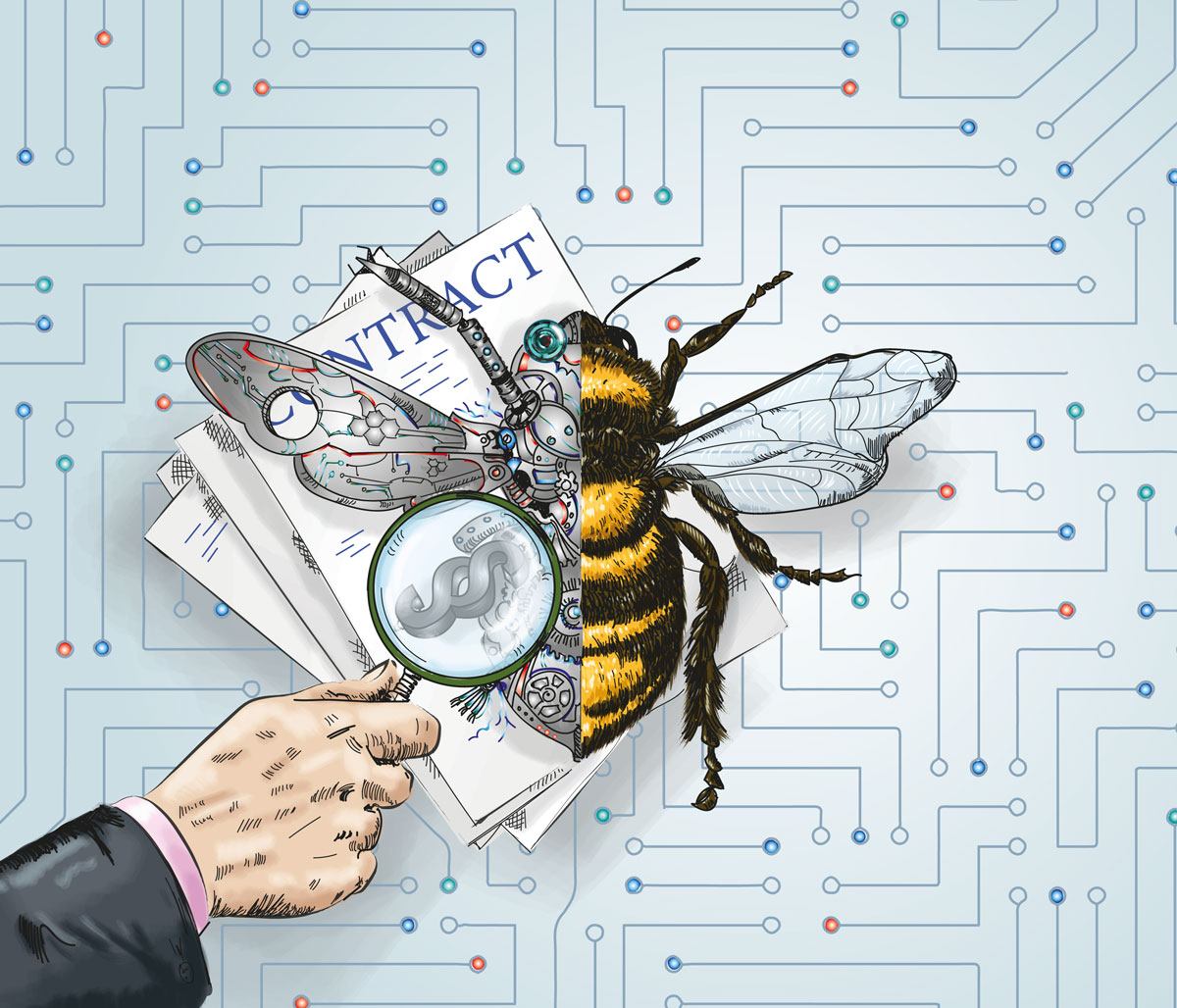

With such a buzz around ‘legal tech’ these last few years, I’ve found myself questioning what people actually mean by the term. Today every firm I meet wants to talk about it, but the definition and understanding of legal tech appears to vary widely and not surprisingly so, as it can encompass a whole host of different technologies, processes, and ideas. So, I decided to speak to four firms – a large international firm, an independent German firm with strong roots in media and technology, a full-service German firm, and an employment law boutique – about how they define legal tech.

To Nicolai Behr, who co-heads Baker McKenzie’s innovation team in Germany, ‘legal tech describes the use of modern, computer-based, digital technologies to automate, simplify, and improve legal discovery, application, access, and manage through innovation’.

Dr Michael Kliemt, founding partner of boutique KLIEMT.Arbeitsrecht, suggests legal tech can be divided into three main categories: first, tech enablers, including network and security solutions and platforms; second, process management, such as case, cost and document management; and third, Legal Tech 2.0, which encompasses document and decision automation.

This certainly cuts to the core of the subject. But SKW Schwarz managing partner Stefan Schicker and partner Dr Stephan Morsch think even one step further: legal tech for them is ‘an approach to support lawyers in providing innovative legal advice to their clients’. This ‘also relates to a certain mindset: lawyers have to learn that their profession is changing and that they have to be more open-minded towards technical solutions if they do not want to lose the connection to the future of legal business’.

Kliemt agrees that ‘any content related to legal tech is to be seen as a moving target with constantly changing market players, solutions and challenges’. Legal Tech 3.0 and 4.0 – revolving around AI and blockchain, which are currently still limited – may be just around the corner in a few years’ time.

Even if others, such as Dr Axel von Walter, member of Beiten Burkhardt’s IP, IT, and media group, speak out against using the term ‘for a vague future vision of AI automatisation in the legal service sector’, there is no denying that legal tech is not just about technology but very much about a mindset or an attitude correlating to a changing nature of the legal profession.

Varying approaches

How then do firms position themselves to keep up with this change? Does it cause fear or do firms see an opportunity? By now it is clear to most that nobody can rest on their laurels; avoiding legal tech is simply not an option. Firms need to keep an eye on developments and be involved one way or another to remain competitive. Yet while some take big leaps seeking to be at the forefront of technological innovation, others adopt a more cautious wait-and-see attitude or try to make use of new technology without big investments.

Skw Schwarz is an example of a frontrunner. ‘We have been observing developments in the area right from the beginning,’ say Schicker and Morsch. The initiation of so-called legal tech meet-ups, a series of events actively promoting the exchange between lawyers, tech companies, publishers, corporations, and financial investors on various topics, has led to the firm establishing its own legal tech company: SKW Schwarz @ Tech GmbH ‘specialises in developing, adapting, marketing, and distributing legal tech products and applications, and it will also provide consulting services in connection with the digitisation of legal services’.

Other firms make the strategic decision not to become a technology company. Beiten Burkhardt follows ‘an unagitated approach’. ‘For us, legal tech is not about becoming a software company but about a positive attitude to use tech tools or tech-based processes to add value for our clients,’ says von Walter.

Indeed, many firms simply try to leverage outside technology solutions to meet business needs for clients. Baker McKenzie has a strong engagement with start-up companies and has partnered with various initiatives, including Barclay Eagle Labs and LitiGate, a Tel Aviv-based venture developing a litigation platform that uses AI to automate legal research and argument assessment in relation to High Court applications.

More recently the firm has also partnered with the Accord Project to assist in the development of industry-wide standards for smart legal contracts, and with ContraxSuite by LexPredict, an open-source contract analytics and legal document platform.

According to Behr, the firm aims ‘for early sight of innovative new technology that enables us to (a) optimise service; (b) better deliver our services; and/or (c) improve how we run our business’. The firm is also the founding sponsor of ReInvent Law, a legal innovation hub in continental Europe, and houses the Whitespace Legal Collab in its offices in Canada, which aims to address changing client needs, new industry dynamics, and the broader role of digitisation across the economy.

Kliemt similarly notes the importance of staying ‘curious, open-minded, and improvement-driven’. KLIEMT.Arbeitsrecht develops tailor-made software products, has launched services like its Arbeitsrecht.Weltweit blog on global employment law issues and has run hackathons. Its dedicated team of ten lawyers is constantly testing legal tech solutions, including document automation, no-code solutions, and early AI solutions. Some tests result in pilot phases and roll-outs. The firm also intends to soon launch its KLIEMT.HR-Tools service for potential clients.

There is no doubt about the rapidly growing amount of legal tech conferences, as well as newly founded associations, hubs, and innovation centres. Critics may point towards the leveraging of legal tech as a marketing tool. Yet the number of serious providers is growing and technical development is constantly progressing.

In terms of its current implementation, the trend seems to point towards a mixed approach: firms both buy off-the-shelf tech and build their own in-house solutions; not wanting to be left behind in the technological race, they opt to purchase various solutions but customise the application to the firm’s or project’s needs.

Kliemt and Schicker and Morsch are in agreement that legal tech is still at the beginning of its journey. It may offer great opportunities, but overall it remains a small market. Nevertheless, while recent talk about legal tech may constitute a bit of a hype, and may give a distorted picture of its current use, it is crucial to recognise and understand ongoing developments, the impact they have on business and client-relationships, and also their limitations.

In other words, digitalisation requires knowledge – and money. As von Walter points out, ‘the ongoing debate on legal tech helps firms to facilitate the process change that is necessary to constantly improve the service level for clients. That is the most impacting role of legal tech today’.

Firms need to consider where digital innovations actually make sense. One should not forget that legal tech is not an end in itself but to optimise legal services to be quicker, better, more cost-effective, and precise. In which areas is it useful and where does it offer added value?

The bigger innovation picture

An even bigger question is perhaps if a firm has to be involved in legal tech to be considered innovative or if innovation doesn’t necessarily have to relate to tech? Von Walter proposes that ‘innovation is not necessarily linked to tech. However, in an increasingly digital driven business environment most innovations will be at least supported by tech’.

Behr expands upon this idea: ‘Technology can be an important aspect in setting up a modern and future-oriented legal department or law firm, but it is only one of three steps, all part of the bigger innovation picture also involving various professions, people, and processes.’ He recognises that ‘technology itself is not sufficient; more efficient service delivery means improving our processes across the business. Collaboration among our lawyers, project managers, process engineers and others is driving this change’.

Indeed one must not forget people as an important factor in all these technological developments, not only as the ones coming up with innovative solutions, but also those to implement them. ‘Innovation is definitely not about technology in the first place,’ says Kliemt. ‘More important factors involve staff and a constant development of an innovative mind-set in the whole organisation.’

Kliemt recognises that the ‘human factor including acceptance within staff and clients plays a major role’ and hence one must ‘pay big attention to involve and encourage all lawyers, but also non-legal staff and clients, to be part of the technological journey’. In fact, the ‘biggest challenge in the long-run might be the training of young lawyers on the job if and when solutions for standard cases will be provided (partly) by technology’.

Schicker and Morsch believe ‘we will see a new generation of lawyers for whom legal tech will be a self-evident integral part of their daily work’. Getting more philosophical about the matter and bringing it to a full circle, they declare: ‘Innovation starts in the mind: if a law firm does not have the right mindset, and if it is still too much bound to old traditions no software will be able to turn it into an “innovative” firm. But at the same time, an innovative firm will not get around making use of legal tech.’

Will legal tech replace lawyers?

Nicolai Behr, German co-head of Baker McKenzie’s innovation and legal tech team and compliance practice

‘Legal Tech is not about replacing a lawyer’s judgement – it is about enabling it. By freeing up time and talent through the effective use of technology, we can make sure lawyers’ skills are used efficiently in solving the truly complex problems our clients face.

‘Nevertheless, legal tech is changing the job profile. In addition to technical understanding and thinking in IT processes, lawyers need to be empathetic, curious, and know a client’s business and their sector like it’s their own.

‘They need to bring industry and commercial insight and analysis to their client work that helps ensure legal solutions answer business questions. One key area for us is to team up with technology vendors in order to provide clients with world class legal advice in a digital setup.’

Dr Michael Kliemt, founding partner of KLIEMT.Arbeitsrecht

‘The core role of a lawyer as a trusted advisor will not be replaced by technology. However, we expect that areas with standardised legal service will be step by step replaced by technical solutions. To that extent, roles of lawyers may become redundant.

Regarding high-end-legal-services we expect a change of roles, role-requirements, skill-sets, and the organisation of law firms. Probably in about five years from now the daily use of technology and mixed tech-legal-teams will be a normal and integrated part of working life for lawyers. Because of this development we already now start to prepare our staff for the required adjustment of mind- and skill-set.’

Stefan Schicker, managing partner, and Dr Stephan Morsch, partner, at SKW Schwarz, both also general managers of SKW Schwarz @ Tech GmbH

‘The legal profession is a people’s business and legal tech won’t change this. We will always need lawyers to work on complex legal matters, and nothing can replace a trustful relationship between lawyer and client. But we will need less lawyers to work for instance on contracts and due diligences – computers will take the lead in all processes that can be easily automated.’

Dr Axel von Walter, member of Beiten Burkhardt’s IP, IT, and media practice

‘The machine will do what the machine can do. Lawyers working on legal commodities will certainly compete with AI and legal tech, and will lose. Our lawyers add more value to the clients than solving a specific legal problem. As trusted advisors they add a trusted client relation. In my view, it will be hard for a machine to become a go-to trusted advisor beyond AI-based legal assessments.’