Reforming data privacy laws may not sound like a move destined to leave an enduring political legacy, but in policy-making circles the tropic casts a surprisingly long shadow.

‘One of the major hang ups of US leadership role has been the absence of a federal commercial privacy law in the country’, says Caitlin Fennessy, research director at the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP).

For many, the most puzzling question of all is why there is still a debate about the issue. In a world where data, and the power to regulate its use, is becoming a central part of statecraft, the United States is conspicuous in lacking a national data privacy law.

A decade ago, when the Obama administration started discussions on strengthening privacy regulations in the US, the business community considered the initiative as an unwanted and unneeded interference. Since then, it has become clear that the alternative may be far less palatable.

‘We are pretty quickly going down the path toward fifty plus privacy laws, which is the same place we have found ourselves with data breach notification law’ says Liz Benegas, general counsel of enterprise management software provider Totango.

Bob Jett, head of global privacy and risk at Crawford & Company, says the case for a federal law has never been stronger. ‘As citizens and consumers, we are only going to increase the number of things we do online. We can also see that some of the largest tech companies are stepping up and saying they want to be accountable for what they are doing in terms of privacy. They have realised that if they don’t self-regulate, the government might come up with stricter regulations than anticipated.’

Privacy, protection and pragmatism

New ways of working and the technology that enable them are creating all-new challenges for businesses – both legal and otherwise – with data privacy a headline concern for corporates of all shapes and sizes. GC speaks to leading professionals from across the WSG network to find out how they are advising clients navigating an increasingly complex corporate environment.

‘Technology has reshaped every aspect of legal life from the way research is completed, to how documents are filed, and, with the pandemic, how we appear in court via remote video platform,’ says Robert McFarlane, a partner at Hanson Bridgett and leader of the firm’s technology and intellectual property practices.

‘With remote applications come increased risks. All businesses, including law firms, must employ electronic and cloud security measures that minimise the chances of data leakage and the compromise of confidential client materials. We invest heavily in security measures and training and advise our clients to do the same.’

Critical to effectively evaluating current measures and implementing training – particularly from the perspective of corporate counsel – is a thorough understanding of the contemporary rules and regulations applicable across all relevant jurisdictions.

‘The keys to mitigating privacy incidents are actions taken prior to the incident itself,’ explains John Babione, a partner at Dinsmore & Shohl LLP. ‘For organisations operating across state lines in the US or internationally, the work done before an incident to know and understand what laws apply to the data flowing through the organisation will reap tremendous benefits for mitigating the harm.’

But in an area that is evolving as quickly as data privacy and protection, staying abreast of the rules of engagement – particularly when extraterritorial considerations are now also frequently at play – and managing the varying expectations and requirements represents an ongoing challenge for general counsel.

To manage this, Batya Forsyth, a partner at Hanson Bridgett and co-leader of the firm’s privacy, cybersecurity and information governance practice, advocates for maintaining the highest possible standards across the organisation.

‘We typically recommend clients comply with the strictest state privacy laws that could apply to their businesses,’ she says.

‘In recent times, this would be California state law—namely, the CCPA and upcoming CPRA, which goes into effect in 2023 and is very often compared to the GDPR, the EU’s well-known, highly-restrictive privacy scheme.’

Managing the challenges of data in the modern corporate environment can’t be limited to just in-house considerations though, with Forsyth advising that external suppliers and contractors be held to the same high standard as internal stakeholders.

‘GCs must have confidence that the vendors critical to the functioning of their business are committed to and are, in fact, protecting themselves as well,’ she says.

Public demand for new privacy laws has tended to be weaker in the US than other developed countries, though the disruptions of the last year and a half – pandemic-related issues like vaccine certificates, digital contact tracing and mobile health apps – have helped put privacy and data security at the forefront of public debate.

A recent poll by data intelligence organisation Morning Consult shows that 83% of voters wanted Congress to prioritise privacy legislation. Surprisingly, those who identified as Republicans were just as likely to hold this view as those who identified as Democrats.

For Cameron Kerry, a visiting fellow at the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution, visiting scholar at the MIT Media Lab, and former general counsel of the US Department of Commerce, the significance of strong data privacy laws goes beyond the short-term benefits it would bring to consumers and businesses.

‘In terms of the international picture, 2021 is a very important year for determining whether people can truly put their trust in American companies and technologies. Businesses want to see a consistent national standard rather than a variety of state standards that mean they have to re-engineer their systems each time they move to a new state.

‘American business has already had to adapt to GDPR, and many companies have internalised a lot of these practices and have acknowledged their advantages for themselves and their clients. There could not be much more fertile grounds for a federal law than we find today.’

Whether or not the US moves to pass a federal data privacy law, the number of states passing their own legislation has ramped up to the point that keeping track of developments can sometimes be a challenge even for the professionals. It also means that, whatever the next four years hold, the state of data privacy in the US is a question every GC will be following closely.

We spoke to those working at the sharp end of data privacy to find out what developments corporate counsel should be paying attention to.

A hill worth fighting for?

The drive to protect private citizens’ data in the US is arguably older than the country itself. Long before he worked to draft the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution, Benjamin Franklin used his position as Postmaster General to ensure the privacy of communications sent by mail (to this day, the Fourth Amendment protects letters from search and seizure).

Subsequent lawmakers followed in this tradition, and in the last 50 years alone the US has introduced several notable pieces of privacy legislation, from the US Privacy Act 1974, which contained important rights and restrictions on data held by US government agencies, to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, which laid down data privacy, security and confidentiality rules for health insurers.

In short, the US has never been inattentive to the importance of privacy. But for GCs struggling to navigate the patchwork of laws across governing data privacy across the country, the big hope is that the Biden administration will finally push for a comprehensive nationwide legislation.

In the run up to the presidential elections in November 2020, privacy specialists were convinced that, whatever the outcome at the ballot, federal legislation would soon follow. Draft bills from both sides of the aisle were circulating in Congress, and when Senators Roger Wicker (a Republican) and Maria Cantwell (a Democrat) introduced the Consumer Online Privacy Rights Act (COPRA) and the United States Consumer Data Privacy Act (USCDPA) in November 2019, it seemed like an often-polarised political system had at last found common ground. That the election ultimately swung in Biden’s favour only served to reinforce this confidence.

‘Parts of the Trump administration had an interest in weighing in on privacy legislation and trying to help move that forward, but there wasn’t any high-level interest in this issue’, says Cameron Kerry. ‘However, Biden, and certainly some of the people around him, have said explicitly that the US should adopt privacy legislation.’

Since then, there have been further signs that data privacy may come into sharper focus. On 12 May 2021, President Biden issued the Executive Order on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity. While cybersecurity and data protection are not the same thing, there is a close relationship between the two on a legislative level.

As Liz Benegas, general counsel of enterprise management software provider Totango comments, ‘you can have security without privacy, but you cannot have privacy without security. We all know the emphasis the US put on national security recently. Developing comprehensive framework for each is difficult and takes time, but now that our systems have been hardened, privacy should be added to the legislation list as well.’

On that list there is already the Information Transparency and Personal Data Control Act, introduced in March 2021 by Representative Suzan DelBene. While the proposed Act is not as wide-ranging as the European Union’s General Data Protection Act (GDPR) or existing Acts applying in certain US states such as the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) and Virginia Consumer Data Privacy Act (VCDPA) in particular – it does not contain the right to access personal information or the right to collect or delete information held by a controller – it does include a pre-emption provision, meaning that, if adopted, it would supersede state laws relating to data privacy.

This, believes Cameron Kerry, points toward a credible impetus for legislative change. ‘There is still the opportunity, interest and conditions to get it done [in the US]. A lot of good work has been done by Capitol Hill in both Houses to understand the issues. Key Republican and Democratic bills in the Senate are pretty close on these issues. A few points still need to be resolved, particularly pre-emption and private right of action, but there are some potential paths ahead.’

Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi has already stated that the House would oppose any federal law that does not include the same level of protection as COPRA, and it is likely that the question of the pre-emption is going to be a huge stumbling block.

However, comments Julia Reinhardt, Mozilla fellow in residence, privacy consultant, and a former German diplomat specialising in EU privacy policy, ‘the Biden administration realises how important this is for industry, for people, for consumers and for international data transfers, so I really hope that it will find ways push this project ahead.’

‘Privacy is a big horizontal topic that regulators have been working on for decades. GDPR may have a few gaps, but it was a big step ahead to have one regulation for a large, contiguous market. The EU member states each had their own privacy laws before GDPR harmonised a general law for the 27 countries.’

Hurry up and wait

While there are of course certain differences of context between the US and EU, the European experience shows that none of the problems facing federal data privacy legislation are insurmountable. Except perhaps one.

Bob Jett, head of global privacy and risk at Crawford & Company, the world’s largest independent provider of claims management to the risk management and insurance industry, believes North America is sufficiently culturally distinct to make any parallels problematic.

‘The unique difference between data privacy in North America and in Europe is that Americans and Canadians, for the most part, do not consider their personal information to be a fundamental right. Most of us are willing to give up our rights to privacy for convenience or speed.’

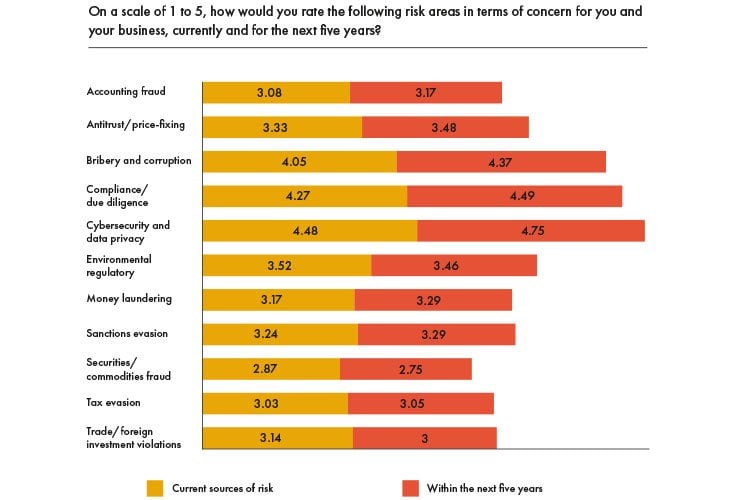

‘In the US, we are much more worried about cybersecurity, because of the potential impact that has on our infrastructure, our ability to use our credit cards, or to get gasoline and to travel.’

A difference in European and American cultures of litigation could also become an issue. While Europe has yet to witness a wave of GDPR-specific class actions, the long-tail of these types of cases makes its difficult to know whether that is because they do not exist or because they are currently working their way through the system. If it turns out to be the latter, it could be a big warning sign for US businesses.

‘Regulations can become litigation tools’, adds Jett. ‘This is one of the things I have been tracking, because in the US, there is a fear for class action lawsuits around this. And such lawsuits have actually started to be filed in California.’

Even supporters of a federal data privacy law concede there is more groundwork to be completed, particularly around the issue of private rights. ‘The question around the rights for individuals to bring lawsuits for privacy violations coming from companies is crucial’, notes Reinhardt.

‘The volume of cases and magnitude of fines tend to be significantly higher in the US compared to Europe, so it may be necessary to include some provision that only allows attorneys general at the state level to sue.’

While these debates play out among lawmakers, GCs will have to go about complying with an increasingly complex patchwork of laws on a state-by-state level. But deliberation among lawmakers does not mean that legal teams can or should take a patient approach to managing privacy.

‘Data protection – both the privacy and security aspects of it – is quickly becoming a risk management function rather than a technological challenge’, says Benegas. ‘Gone are the days when only the chief technology officer needed to know or care about the issues. Nowadays, all levels and functions within a company need to know and be prepared.’

‘GCs and corporate counsel will play a pivotal role in helping shape the response to this challenge, not only because risk management is part of the job description but because of the broad view legal teams have into company operations, from human resources to vendor management to customer contracts.’

Ann Cavoukian, former Information and Privacy Commissioner for the Canadian province of Ontario and originator of the concept of privacy by design, which was subsequently incorporated in GDPR, also advocates a proactive stance when it comes to data privacy in the c-suite.

‘In these times of legal limbo, I always encourage companies to get a certification. First, it builds trust and business relationships, which has been lacking for a long time. Second, it increases the quality of the information they collect.’

‘There is no inherent tension between granting privacy and exploiting economic value when it comes to data. You can capitalise on data but strip it of all personal identifiers. One of the seven foundational principles I established with my privacy by design approach is to abandon the zero-sum models, where it is either-or or win-lose. There should not be a conflict between business interest and privacy. We should be aiming to satisfy both.’