Future finance

Cryptocurrencies and the blockchain technology underpinning them have seen exponential adoption over the past ten years. Perceived failures of the status quo and a desire from innovators for improvement has meant that today, cryptocurrencies are now widely accepted in many corners, from retailers to charities to governments. The underlying technology is finding wide application, being used to reinforce supply chains and preserve evidence.

The explosion of digital assets has been enabled by blockchain technology. A blockchain is a series of mathematical structures, inside which individual transactions are recorded. The record of each transaction – each ‘block’ – is dependent on the block that came before it, and becomes a permanent part of the history of the blockchain. This means that the record cannot be tampered with: once it is added to the blockchain, all subsequent transactions are recorded in relation to that block and all of the blocks that came before it. Following each transaction, the updated blockchain is distributed to each participant. Any attempt to change a record in the blockchain will put it at odds with the version held by every other participant in the blockchain, as well as all of the subsequent transactions that have been recorded.

‘Blockchains are basically networks – a series of computers – that rely on a process system of interconnected computers who validate transactions,’ explains John Roth, chief compliance and ethics officer at Bittrex.com. Bittrex is a US-based cryptocurrency exchange with a large clientele of institutional investors. He is also a former US Department of Homeland Security Inspector General and Department of Justice prosecutor.

‘In plain English, there are computer operators who are ensuring that the networks are healthy and that as you engage in transactions, these are actually valid transactions. Most folks aren’t doing it for free, they’re doing it because they’re incentivised by crypto currency. So, blockchain is more than just value transfer.’

‘Crypto is getting less and less risky because there are more and more providers of services which have been in the business for multiple years which educate the people,’ describes Lars Hodel, Head of Legal and Compliance Bitcoin Suisse AG, which was established in 2013 and is the first Swiss-regulated financial intermediary specialising in crypto-financial services.

‘If you want to buy Bitcoin or get crypto asset exposure today, you don’t need to log into some shady-looking site, you can just Google and find your providers to see that it’s real people. Access to crypto assets is getting easier.’

Dangerous money

Some sceptics of the digital asset revolution point to the difficulty of protecting against criminal misuse: after all, regular currency has financial institutions mediating each transaction and leaves a supposedly identifiable paper trail. The anti-money laundering battle is big enough with traditional forms of currency, so how can digital currencies avoid criminal misuse?

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that US$800bn to $2tn is laundered every year – most of this being in cash. According to the Chainalysis 2019 Crypto Crime Report, US$2.8bn in Bitcoin was laundered by criminal entities in crypto exchanges.

‘One of the key benefits from blockchain is user autonomy in that users are able to control how they spend their money without dealing with an intermediary authority like a bank or government,’ says Swadesh Gupta, Director of Legal and Strategy at Wallet Circle, a hyper-local customer engagement platform.

Roth expands: ‘There’s a fallacy out there that somehow these digital currency transactions are secret – actually, nothing could be further from the truth. These are very transparent transactions, you can identify transactions by date, time, amount and blockchain location.’

‘It resolves the trust issues in a transaction, and the transactions on blockchain are totally transparent,’ adds Gilbert Ng, legal counsel at Huobi Group. Huobi Group is a world-leading company in blockchain and digital asset industry with a mission to making breakthroughs in core blockchain technology and the integration of blockchain with other industries. It has over US $1bn trades occurring daily on their cryptocurrency exchange.

Washing dirty cash

Criminals are able to use crypto money laundering to disguise the criminal source of their cash assets employing a combination of different approaches. The most simple method of money laundering banks on the fact that undertakings made with cryptocurrencies are pseudonymous.

‘The reason that criminal activities increasingly involve digital assets is because of the anonymity features of these digital assets,’ says Ng. ‘But, looking at the recent trends, there are actually fewer criminal activities using digital assets for laundering.’

The usual approaches that apply to conventional cash money laundering also apply to crypto-laundering. There are three key phases of (crypto) money laundering: placement, hiding and integration.

Placement is moving the dirty cash from its original source into a legitimate cryptocurrency system.

‘The first crypto placement stage is super important to focus on,’ explains Roth. ‘Any time that there is a bridge between fiat currency and digital currency, you really want to pay attention to it.’

This is done through often loosely regulated crypto exchange platforms and initial coin offerings, right through to the use of cryptocurrency ATMs which have already proliferated throughout bars and grocery stores around the world. The complicity of crypto ATMs in the process highlights one of the reasons these novel digital assets are being used to launder criminal funds. What might initially be thought of as a necessary lowering of the barrier for widespread crypto adoption now represents an easy access point for moving dirty money into the digital financial system.

‘We know that in the placement stage, people transact with crypto ATMs,’ explains Rory Gordon, legal and compliance officer at Coinfloor, the UK’s longest established Bitcoin exchange.

‘We’ve had concerns from the police before because [crypto] ATMs have been particularly popular with drug dealers, seeking to convert large quantities of cash. A popular way to get rid of that cash is through [crypto] ATMs because you can deposit the cash, get the Bitcoin, and from there it’s much easier to make up a backstory as to where you got it all from.’

There are also the more conventional concerns at the placement stage, as Hodel explains:

‘It’s very easy to ask your friends to deposit money for you or ask a stranger if you can use his ID to open an account. These are the things that we see which are the most used cases in money laundering. These are very traditional, non-blockchain, non-crypto attack factors that you’ve had in the traditional banking world for years.’

The ‘layering’ phase

The second stage, hiding or ‘layering,’ conceals the origin of the dirty cash through a sequence of transactions and financial tricks, moving the cash through different accounts, currencies and exchanges to obscure its true origin. Just how effective a would-be launderer can be using digital assets will depend on the asset itself and the infrastructure used to deal with it. Some cryptocurrencies have specific focus on privacy, such as Monero. Others do not.

As Roth describes, all transactions are recorded on the blockchain, which provides a level of transparency which ultimately makes complete privacy difficult. Monero circumvents this. Monero transactions hide the sender by ‘signing’ each transaction with multiple signatures, only one of which is that of the actual sender. The amount being sent and the receiver are similarly private.

‘It depends largely on whether they’re using regulated exchanges. In the EU, US, Canada and Australia, the exchange networks are very heavily regulated and require verification procedures that make customer identification and law enforcement considerably easier. So, if a criminal uses one of those exchanges it’s almost a trivial exercise to be able to expose them. And because digital currency transactions are publicly indelible, all they need to do is cross-exchange once and it can be traced all the way back,’ explains Roth.

Hodel expands further, adding that: ‘Even if you use privacy coins where you can’t trace transactions, you need to explain why you used that coin. Any provider who sees a client using privacy coins on a large scale needs to question their client about why they’re using them. If a provider sees an unusual fund and analyses this on a professional level, then this will be flagged.’

‘When you look at currencies such as Monero, they use ring signature encryption which makes it incredibly difficult for any company to track the source of that asset,’ says Gordon.

‘However, some privacy coins do have keys to reveal the true owner of the assets which must be given over if there’s subpoenas or relevant court orders, but generally privacy coins allow virtual anonymity.’

‘Technically, criminals can stay anonymous under blockchain,’ says Ng.

‘But, practically, no. Most criminals will use crypto exchange platforms or over-the-counter (OTC) agents to convert digital assets into fiat currencies. In such cases, their identities would probably be revealed if proper KYC (know your client) procedures are in place.

‘It’s a fairly easy exercise to see through what’s really happening,’ says Roth.

‘With decentralised exchanges, it depends on what the exchange looks like and how it operates. It may make it more challenging, but no more challenging than tracing traditional money laundering through traditional banks.’

‘But, the risk that exists in cryptocurrency that doesn’t exist in typical currencies, is the idea that you can do a peer to peer transfer of value: I’m a bad person, you’re a bad person and we want to do some sort of financial exchange. We can do so with cryptocurrency without involving a bank or a credit card company because peer-to-peer transfers are with cash. This is a new paradigm for criminals to exchange value without somebody looking over their shoulder.’

The final stage, integration, involves the newly laundered money being returned to the launderer with an apparently legitimate – or at least, unknowable – legacy. If money reaches the integration stage, it becomes much more difficult to trace back to its criminal origins from that point.

Anti-moneylaundering solutions

Considering that blockchain technology administers a public log of each and every transaction – leaving behind a permanent trail – susceptibility to money laundering through cryptocurrencies is somewhat manageable.

‘Even if you are a weak provider or intermediary in the placement phase, who doesn’t take anti-money laundering (AML) seriously, I can still check that in the integration phase at a later stage on the blockchain, which is great because you can’t do that in the traditional banking world,’ says Hodel.

‘It’s wrong to say that cryptocurrencies can facilitate money laundering. Cryptocurrencies can be used for money laundering like any other asset, be that fiat, art or even physical precious metals. In the beginning, technology is usually used by people who want to take advantage of the fact that some technologies are not used very broadly.’

‘It was exactly the same with the internet, people used it to hack things and then today you still have online banking, despite the hacks. With crypto, it’s the same – it was used by people who wanted to try to find a new way across the banking system, to money launder.’

But while cryptocurrency is not the ultimate enabler of laundering that it is sometimes accused of being, stamping out money launderers requires supervision and a commitment to compliance on the part of companies within the ecosystem.

‘What helps is installing an in-house legal and compliance department and then training people – not only on the technicalities, but, also on what AML exactly is. Technical understanding is crucial. You need to know what you’re dealing with. If you take a retail compliance officer, you probably wouldn’t get the compliance challenges that you would expect from a tri finance bank and vice versa,’ adds Hodel.

Gordon echoes this sentiment: ‘Having a compliance and legal department and having the right policies and procedures in place, actually gives you the tools to tackle this. Of course, you need to obtain the necessary documentation on your customers. You need to know who they are but you also need to monitor their activity and have intelligent checkpoints in place.’

Though bad actors will continue endeavours to bypass and manipulate blockchain, money laundering can be prevented with devices that pair consumer data with their respective crypto transaction records. These tools can make it relatively easier for businesses to clamp down on crypto-laundering, stay AML compliant and isolate high-risk clients.

‘With crypto, there’s nothing new under the sun, this is simply a different sort of take on typical value transfer, but the measures for AML are largely the same,’ says Roth.

‘You have to KYC and understand your customer’s business, so you can understand what typical business transactions look like and have alerts generated for transactions or a series of transactions which deviate from the expectation of what that customer is doing. You must have good AML hygiene. It really isn’t all much different than what traditional financial institution programmes look like.’

Clean regulation

Globally, when it comes to cryptocurrency transactions and AML enforcement, the law drastically differs from jurisdiction to jurisdiction: from relatively strict regulations in the likes of UK, the US, and much of Europe to practically non-existent enforcement in many other countries.

‘Money laundering is an international crime and money launderers, just like other criminals, don’t respect international boundaries,’ argues Roth.

‘The ability to coordinate, harmonise and correlate these individuals to laws in a way that levels the playing field, among many different countries, with a uniform set of standards of laws that every country follows is super important. Otherwise, you get a regulatory arbitrage where money launderers will gravitate towards to weakest regulatory scheme.’

‘Like any nascent industry, one needs to be very aware of the risks that surround the crypto industry, especially when dealing with non-regulated entities,’ notes Jonathan Galea, CEO of BCA Solutions and a long-standing crypto-focused lawyer who wrote his 2015 Doctorate of Laws thesis on crypto and AML.

‘In fact, most companies would treat crypto as a high-risk industry. However, one needs to differentiate between the various service providers and stakeholders involved in the industry, versus the actual technology powering crypto as we know it. The latter, namely blockchain technology, has proven to be a far better tool for tracking and tracing movements of money than traditional technologies. This is precisely the reason why one shouldn’t go overboard, or essentially over-regulate, before a sufficient understanding of a new technology and its repercussions is obtained, and then proceed to assess the various stakeholders in a particular industry in order to regulate them properly.’

Arguably, the general lack of consistent global regulation is creating considerable risks in increasing the scope of potential manipulation of cryptocurrencies by criminals – therefore, the effectiveness of such protections against money-laundering is somewhat questionable and perhaps even discourages the broad scale adoption of cryptocurrencies.

‘One of the biggest challenges is that we’re not all speaking a common language across jurisdictions in terms of enforcement,’ adds Liat Shetret, Senior Advisor for Crypto Policy and Regulation at Elliptic, a blockchain analysis provider which specialises in crypto compliance and risk monitoring technology.

‘Without standardisation, the regulatory nuances between nations can be exploited. If there is a loophole, it will be found by bad actors, especially if there’s an assumption they won’t be caught because they assume their activity on the blockchain is anonymous. What many don’t realise is that all cryptocurrency transactions on the blockchain are immutable.’

‘There’s a vast disparity between the EU and the US on the one hand, and what I would call the under regulated countries, on the other hand,’ says Roth.

‘There needs to be more global coordination, and less tolerance for countries that prevent core regulation, so we have the cryptocurrency exchange market which is not completely dominated by these large exchanges who are purportedly registered in the Seychelles, Malta, Hong Kong or Singapore, but are in fact, not regulated at all.’

However, Gordon argues that the possibility of exploitation by criminals is being eroded:

‘It’s definitely an issue, but it’s being mitigated this year by the 5th EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive – so that’s the reason for the Financial Conduct Authority taking crypto under its wing. We’re seeing a lot more global co-operation with crypto compliance now.’

‘Global regulations are developing and on the right track, but it takes time for regulators to acquire sufficient knowledge of this industry,’ adds Gilbert Ng.

One of the biggest challenges facing in-house legal teams is one of compliance with everchanging AML and crypto regulation through differing jurisdictions.

‘This is one of the risks that we face. We need to vet every country – literally – for what is allowed and what isn’t. It differs even if you’re EU member states. That we do not have a unified approach towards this is something that makes it extremely difficult,’ adds Hodel.

Roth agrees. ‘There’s a variety of legislation that we deal with. One issue we have here in the US, you probably don’t have as an issue in the UK or the EU is here, is that we’re also governed by state law. So, because we’re operating in all 50 States, we are required to be compliant with state law as well as federal law. So the biggest challenge that we have is scanning a variety of different laws that apply to us and ensuring that we are in compliance with that.’

However, Hodel argues that ‘if you’re working in the financial industry, you’re used to having different legal and regulatory frameworks apply to your product. It would be nice to have one law that is applicable to any situation worldwide but this is not how law works. Just because crypto is not part of the financial market regulation yet, we still have the very basic civil and penal codes which, for example, provide punishment for fraud. We have a common understanding of what should be okay and what is not okay, and this doesn’t change when we’re dealing with crypto.’

Crypto disruption

Despite the fact that cryptocurrencies can indeed be used to conduct illicit criminal activity, the principle impact of such currencies on illicit crimes, such as money laundering, when juxtaposed to cash transactions, is little to none. According to The Foundation for Defense of Democracies and Elliptic’s 2019 report, US$829m Bitcoin was spent on the dark web. To put these figures into context, that’s only 0.5% of all Bitcoin transactions, with 2 to 5% of global GDP, or up to US$2tn through the traditional financial institutions.

‘Money laundering is not as big of an issue in the crypto space as it is often reported to be or often perceived. It’s a misconception and it’s actually very easy to counter,’ maintains Gordon.

‘We’re still in the early adopter phase of cryptocurrency,’ says Roth.

‘In the grand scheme of things, it’s just a tiny fraction of the global financial world. But, I think cryptocurrencies will reach a tipping point where it’ll be common for you to have a Visa, Mastercard and a cryptocurrency backed debit card in your wallet to engage in transactions. We think that the next two to five years will be a mainstream adoption of cryptocurrencies in a way that will fundamentally change the volumes of crypto involved, as well as the risks.’

Gordon agrees: ‘In the coming years, we’re going to see mass adoption, with big traditional financial players eventually entering the crypto industry once the regulation comes in. Crypto will be used as a store of value for a lot of unbanked individuals. Last year around 1.7 billion people were without banking globally. The great thing about crypto is that you can easily set up a wallet by yourself on the phone or computer. I think it has enormous potential to transform economies and provide opportunities to people the world over.’

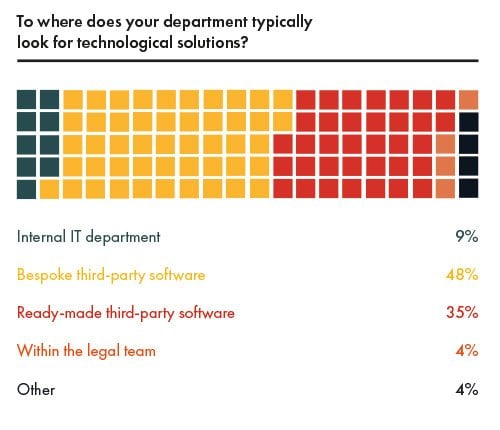

Carl Watson, general counsel for Asia at design and engineering consultancy Arcadis, underlines the value this brings to the legal team.

Carl Watson, general counsel for Asia at design and engineering consultancy Arcadis, underlines the value this brings to the legal team.