Beginning in June 2019 with a series of uncontrolled blazes, Australia’s bushfire season – since dubbed the ‘Black Summer’ – has spiralled into one of the worst on record in the country, causing widespread devastation to communities and wildlife.

By the end of January 2020, the fires had claimed more than 30 lives, burned through millions of acres of bush, forest and parks, and led to the deaths of an estimated one billion animals – with fears that some endangered species have been driven to extinction by the disaster. Over 2,000 homes have been destroyed and countless communities evacuated by the unprecedented ferocity of the bushfires. Smoke from the flames has caused disruption to major metropolitan areas such as Canberra, Sydney and Melbourne, with the air quality in Australian cities sinking to among the lowest in the world at various points throughout the crisis.

The crisis has impacted all sectors, as businesses, government organisations and charities were called into action to battle the flames – either on the front lines, or behind the scenes. With the legal function playing an ever-increasing role in the management of crises of all kinds, in-house lawyers throughout Australia are diligently working to play their part in the management and mitigation of the unfolding disaster.

Feeling the heat

The scale of wreckage caused by the fast-moving Australian bushfires has been catastrophic, and has placed a lot of pressure upon organisations involved in the relief effort. But, for general counsel on the ground, their response to the tragedy has been similar to that of any crisis.

‘The bushfires are no different to any other crisis that in-house lawyers can face. I have worked in other industries throughout my career and this is no different. Crisis is something that is faced by all in-house lawyers at some point in their careers,’ says Tara Eaton, head of legal and policy at Australian Red Cross.

Australian Red Cross is a humanitarian and community services charity that has raised over AU$127m towards the bushfire disaster relief effort.

‘At the Red Cross, we do have an existing framework within the team and we build on that during times of crisis. For example, the team is set up to have a lawyer dedicated to a particular department – with that, we are able to build stronger relationships,’ says Eaton.

‘Therefore, in a crisis, different departments within our organisation immediately think of legal. They get you involved in the crisis management team from the beginning and, because of that, you are abreast of issues as they develop, you are part of the team that sits on daily, or even sometimes multiple times a day, update calls.’

The pressure to deliver timely, accurate and efficient legal advice is well-covered ground for in-house counsel, but in times of crisis, where life is at stake, this imperative only intensifies, explains Eaton.

‘One of the most challenging things in a crisis is being able to provide ad hoc legal advice. Not knowing all the information, but still having to make a call on things because the issues are moving so quickly, is difficult. One of the greatest skills for in-house counsel everywhere is the ability to trust your gut,’ she says.

‘This is a necessary skill in a crisis. Having knowledge of your industry, business and the requirements to make decisions is essential to providing the best guidance you can at any particular time. So we have been doing that as a team, as the bushfires have been developing. We have been issuing daily emails to support our colleagues, saying here is today’s legal guidance, and we build on that as the team faces additional questions.’

‘During a crisis, general counsel need to show compassion and understanding for members of their organisation, while maintaining a clear head and providing objective legal advice under pressure,’ agrees Katrina Bullock, general counsel at Greenpeace Australia.

‘This requires resilience, a strong support network and self-care.’

Also feeling the pressure to provide speedy legal advice during this crisis is Sarah Donald, general counsel of Sunshine Coast Council. The Sunshine Coast is just one of many local councils across the eastern seaboard of Australia that have felt the devastating effects of the bushfires.

‘The recent bushfires presented unprecedented challenge to our community, with the immediate evacuation and displacement of thousands of people,’ says Donald.

‘It is absolutely necessary to provide ad hoc legal advice in response to a crisis situation.’

Sow the seeds

With times of crisis adding more layers of pressure to lawyers already grappling with the demands of the in-house job, steps taken pre-crisis can go a long way to ensuring the response to disaster situations is efficient and as stress-free as possible. Having systems in place aimed at mitigating risk during times of crisis is essential to providing effective legal advice.

‘Bushfires are not uncommon in Australia,’ says Donald.

‘As a result, significant systems are in place to manage these events. In Queensland, these are managed pursuant to the Queensland Disaster Management Act 2003. This Act outlines the principles of disaster management in Queensland.’

Provisions under the Act provide a legal framework for local councils during times of crisis, covering the disaster response capabilities required of local government and the training required of those involved in disaster management.

‘Local government is responsible for managing disaster events in our local areas, and this is done through our Local Disaster Management Group (LDMG). Our LDMG is coordinated by the Sunshine Coast Council, and membership is made up of liaisons from all emergency agencies (police, fire, ambulance, State Emergency Services), as well as community service providers (both government and non-government) and media representatives,’ outlines Donald.

‘The Council and in particular our disaster management team, works very hard to ensure we have excellent relationships with our emergency services partners, so we are able to have seamless operations when we are required to activate our disaster management plans and coordination centre in response to events affecting our region. These relationships were essential when we were managing the recent bushfires in our region.’

The importance of cultivating relationships extends to external counsel to whom the legal team can turn when crises demand specialised legal advice, fast.

‘You may be called on to give urgent advice on specialist areas that are not necessarily within your own expertise – then it is good to have good relationships with advisers that you can call on quickly,’ explains Astrid Heward, general counsel and general manager at the Bureau of Meteorology in Australia.

Bigger Picture

The crisis highlights the need for organisations and their in-house teams to be appropriately prepared pre-crisis, and efficient in the provision of advice mid-crisis. But, for some organisations, their work will stretch far into the future, beyond the crisis of the day.

‘We have a professional duty to ensure that our response is not just limited to the immediate effects of these fires, but rather focused on the root cause,’ explains Katrina Bullock, general counsel at Greenpeace Australia.

‘Climate change is driving catastrophic bushfires. This is a coal-fired crisis: coal is driving both the bushfire crisis, and the Australian federal government’s inaction on climate. We have ignited the shared social and economic power of Australians through our climate petition, which demands that the federal government respond to the bushfires by declaring a climate emergency and taking action to mitigate climate change. Over 81,000 people have signed to date. Across the organisation, we continue our multifaceted work to support renewable energy investments and dismantle the systems that support the climate crisis; to hold those responsible for contributing to climate change accountable – in the streets, at the ballot boxes, in financial markets and in the courts.’

She adds: ‘It is becoming increasingly important to embrace new, time-saving technologies and ways of working that empower our crew to make well-informed, timely decisions. I think we will also see increasing climate-related litigation against Australian directors who have acted negligently in ignoring climate risks, and a surge in activist investors who boycott fossil fuels. This will generate some interesting and complex legal work in the years ahead.’

‘For example, I’m no expert in industrial relations, so I have a couple of advisers I trust that I can call to bounce things off quickly.’

However, when time is of the essence, it is ultimately up to in-house legal teams to make initial assessments and provide preliminary legal advice in times of crisis.

‘Our external firms have been very supportive, but in a crisis you do not have a lot of time to go out to external counsel,’ says Eaton.

‘I have always described the role of in-house counsel as being a GP: we diagnose the head colds, the broken ankles, and then decide if we need to go out and see an ear, nose and throat surgeon. But we as in-house counsel are doing the first diagnosis of what is wrong.’

In the end, whether seeking guidance from external advisers or relying on internal resources, general counsel depend upon on the relationships they have developed.

‘To me, it boils down to relationships – we as lawyers work really closely with our colleagues to understand the issues that arise, and then work with them to find solutions,’ says Eaton.

‘It is important for in-house counsel to not become the department of “no” – of course we have to be that in this role sometimes – but particularly pointed in a crisis are the relationships you have built that enable you to have a seat at the table. Your practical guidance can be implemented very easily in a crisis; because you do not have a lot of time, you do not have the ability to come up with new policies and procedures – you just have time to give short, sharp guidance to help.’

Where there’s smoke there’s fire

Managing the legal efforts from the skies is Heward at the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM), an executive agency within the Australian government responsible for compiling weather forecasts, warnings and observations and delivering them to the Australian public.

‘The Bureau’s mission is “to provide trusted, reliable and responsive weather, water, climate, and ocean services for Australia – all day, every day”, and Bureau staff have a very strong sense of public service,’ explains Heward.

‘The majority of the work that my team does to support our operational groups during the extreme weather season in fact happens when Australia is not in its “severe weather season”.’

Australia’s severe weather season traditionally occurs in spring and summer, and features weather events such as drought, severe thunderstorms, flooding, tropical cyclones and bushfires.

‘A key factor in the success of the emergency service response to the bushfire crisis is the collaboration and co-ordination between the various agencies that are involved in the response effort. The legal team supports this with MoUs [Memorandum of Understanding]/agreements that facilitate the Bureau’s meteorologists to be embedded in the emergency services as required in extreme weather events.’

Nevertheless, as with many crises, planning can only take you so far. Severe weather is, by its nature, extremely volatile. Emergency situations are inevitable. When adversities such as the devastating Australian bushfires occur, general counsel are relied upon to provide fast, accurate and essential legal advice.

‘If I am called upon to give urgent advice, I try to keep an eye on the bigger picture, and the risk levels, to understand how the advice needs to be prepared and presented. It’s obviously important to give the right answer, but “right and done” is better than “perfect”,’ outlines Heward.

‘One of the most challenging issues that arose in my role over the last couple of months related to the Meteorological Authority Office. Under the Civil Aviation Regulations, the Bureau’s CEO is able to authorise equipment to be used to provide reports for use in forecasts for the purposes of civil aviation.’

Thick plumes of smoke that wafted into cities had an adverse effect on the visibility of crucial airport services. Providing visibility reports are essential. However, equipment used to provide such reports was not always regulatory compliant to measure smoke particles.

‘Existing runway visual range (RVR) equipment at certain airports in Australia was already authorised for the purposes of providing reports in relation to fog/mist, but not for other types of lithometeor particles (such as smoke),’ says Heward.

‘Due to the serious smoke haze experienced at these airports, the Met Authority team had to work urgently to manage the complex regulatory and technical matters that allowed for the RVR equipment to also be authorised for smoke.’

Paved with good intentions

On the ground, in-house counsel are supporting organisations dealing directly with the physical fallout caused by the bushfires. Life-or-death videos from inside the inferno have been viewed by millions of people across the globe, with the destruction sparking an outpouring of donations from those eager to help – both financially, and otherwise.

‘The images of the bushfires have been broadcast worldwide,’ explains Eaton.

‘The world is a much smaller place because of the speed in which news travels and just the outpouring of support from Australia has been phenomenal, as well as the outpouring from all parts of the world: Mongolia, Estonia, and the US – every corner of the world knows about the bushfires and wants to help. This is humanity in action.’

Greenpeace Australia has also drawn attention and support to the cause.

‘We raised over $74,000 on behalf of the Rural Fire Service to support their work in battling the fires on the ground,’ says Bullock.

‘Additionally, we have provided a platform for bushfire survivors to tell their stories to the world, and our creative team has been busy documenting the destruction of homes and nature to help people truly understand the effects of climate-related emergencies.’

The response of people wanting to donate to the cause has been overwhelming, and has been helped by social media. But, while undoubtedly positive, charity in the 21st century raises unique questions that must be addressed by legal teams such as Eaton’s.

‘A lot of the issues that we have been working through relate to the proliferation of social media and people sharing our fundraising links,’ she explains.

‘This is therefore raising questions: can we accept donations from overseas? What are our limitations with respect to the donations? How do I characterise those donations? Could we be considered fundraising in other jurisdictions? If so, what does that mean?’

‘Coming up with this guidance in the online space can be very difficult, because you might have one link in Australia which now can be shared globally. Nowadays, those issues are just tricky for all businesses to navigate.’

‘This is not just relevant to us in this particular situation – talking about disasters – but I am sure many other legal counsels are faced with the issue of how do we make our laws, which are jurisdictionally based, relevant to a global online environment.’

Overcoming this challenge, Eaton focused on drawing legal similarities to other similar situations.

‘How I characterise this is similar to a financial services organisation,’ she says.

‘When they are running an IPO, you are getting money from the public to do something – namely, an IPO is aligned to accepting donations from the public – and with that comes great responsibility to make sure you are telling people accurately where that money is going, how that money is being spent, and where those funds are going to be allocated.’

‘So one of the more tricky issues we have been managing is around the social media response and global organisations wanting to fundraise on our behalf – what does that mean from a regulatory perspective?’

As in-house counsel operating on the front lines, crisis management should be viewed through multiple lenses, stresses Eaton.

‘Part of our role, I think, as legal is to not only approach things through a legal lens but, in times of emergencies, to also bring a different focus. By looking at it through the eyes of our donors – our very extraordinarily generous donors – as well as the community, we have to consider: what are their expectations? What are the needs of the community we are trying to serve? How are we balancing those needs? How are we trying to do the most good we can, and support people in this challenging time? All whilst making sure we have all the checks and balances in place.’

At your own risk

Whether battling the fallout of a financial meltdown, supply chain interruption or environmental disaster – such as the Australian bushfires – crisis management is a core skill for general counsel, irrespective of the industry they represent. Counsel will be relied upon to give efficient, fast and accurate legal advice during emergencies, and play a key role in navigating the business through complex regulatory challenges and obstacles in times of disaster.

Despite having to overcome major legal obstacles, the scope of legal work can be rewarding for those on the front lines, believes Eaton.

‘It has been fascinating, actually. One of the things I love about being in-house is the diversity of work that we are faced with on a daily basis, and when there is a disaster, such as the bush fires, it has really come to the fore.’

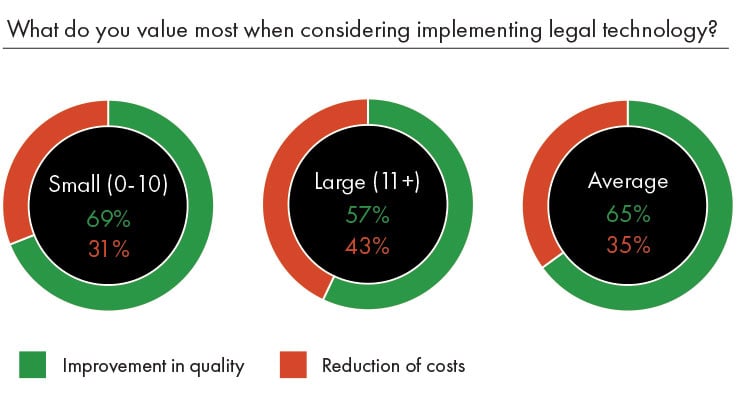

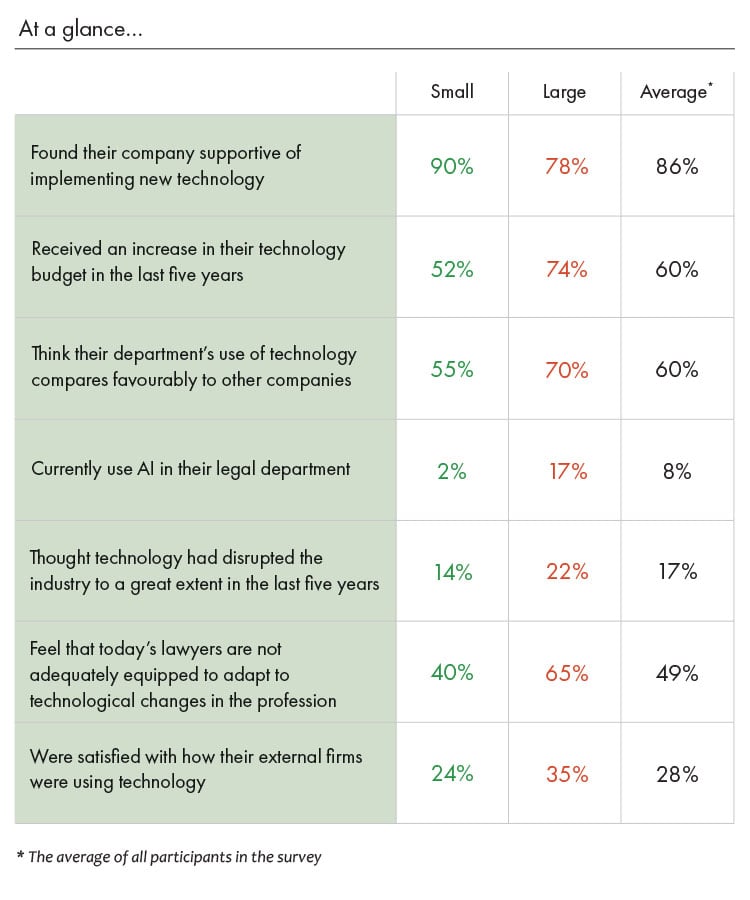

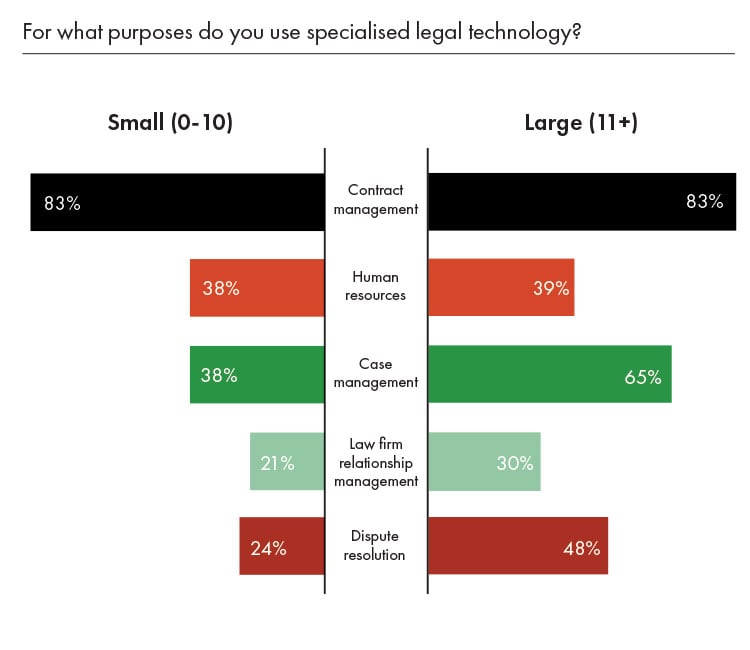

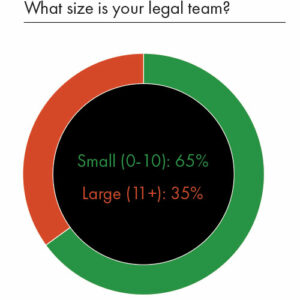

In-house legal teams come in all shapes and sizes: some companies will have small teams, preferring instead to outsource the bulk of their work to external firms, while others have internal legal departments that would outnumber many major law firms. For the purposes of the research that underpinned this report, a small legal team is classified as one with ten or fewer members, while a large legal team is one with more than ten members.

In-house legal teams come in all shapes and sizes: some companies will have small teams, preferring instead to outsource the bulk of their work to external firms, while others have internal legal departments that would outnumber many major law firms. For the purposes of the research that underpinned this report, a small legal team is classified as one with ten or fewer members, while a large legal team is one with more than ten members.