At a time of increasing regulatory scrutiny in virtually all corners of business, and with the stakes having never been higher, now is the time for companies to get their house in order in terms of their compliance and investigatory response regimes. Our survey of top in-house counsel from across the globe revealed great disparities between organisations, not just in terms of how they plan for a potential investigation or prosecution, but also in terms of how high a priority such an endeavour is, and who within the business is best placed to take ownership of it.

But while most businesses – and certainly nearly every lawyer – would recognise the risk of inadequate preparation in this area, whether this recognition had translated into action is another story. Just 57% of respondents in our White Collar Investigations Survey reported that their organisation had implemented a response plan for regulatory investigations or white collar prosecutions. 39% reported that their organisation has no such plan.

49% of respondents felt that their company had robust and effective investigative protocols in the event of an external investigation; 29% said that they did not believe that they had such protocols and 22% were unsure.

While it might first seem reasonable to assume larger companies are more well-resourced and thus more likely to be in a position to create an investigatory response plan, this does not appear to be the case. In looking at whether respondents’ organisations had implemented a response plan, those from larger companies (with over 100 employees) were less likely to report their organisations as having implemented a response plan, at a rate of just 57%, compared to almost 80% of those from smaller (less than 100 employees) companies.

‘There can often be too many distinct business units that would be involved in an organisation-wide plan. What you end up finding is in those cases, it’s much harder to get a far-reaching plan together as in-house counsel,’ says one legal director in the Australian telecommunications sector.

‘It is very important in our view to avoid a culture where the operating commercial organisation believe that no written guidelines from the top of the organisation means “green light”,’ says Kjell Clement Ludvigsen, general counsel at Norway’s Nortura.

‘It should be very clear to all that they are responsible themselves for what they do, but they should ask for assistance from legal or compliance if they are in doubt.’

Preparedness

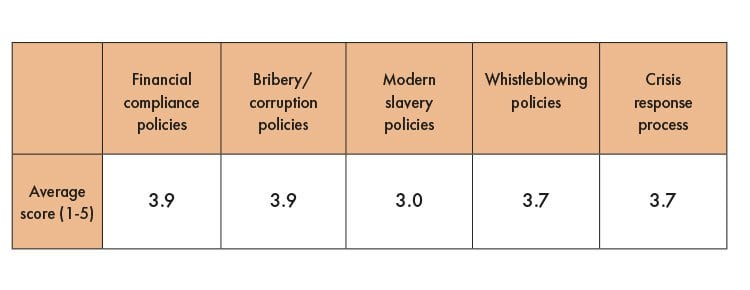

Another problem with trying to get a clear view of where businesses are in their white collar investigations risk is that areas of concern will differ from company to company, and sector to sector. Our survey asked respondents to rate their level of preparedness in a variety of key areas on a scale of 1 to 5, with one meaning ‘not prepared at all’ and five ‘very prepared’. On average, respondents reported that their business was most prepared in terms of their financial compliance policies, scoring an average of 3.9. Companies were least prepared in terms of their modern slavery policies, which came in at an average of 3.0.

Those who said that their organisation had implemented a response plan for regulatory investigations or white collar prosecutions reported being more prepared almost across the board than those who did not. In particular, respondents whose organisations had such a plan rated their preparedness, on average, up to a full point higher than those who did not. In particular, both bribery/corruption policy and modern slavery policy preparedness increased by almost a point (0.97 and 0.92, respectively) from companies without a plan compared to those with one.

‘Aramco has zero tolerance in relation to any anti-bribery and corruption activities,’ says Ahmad Ismail, general legal counsel at Saudi Aramco Shell Refinery Company.

‘Therefore, I align my plan backwards from there. At each board meeting, I will align this with my president – I will check if there are changes, or any fine tuning for the plan. We need to be agile yet able to optimise.

‘Particularly now, as we have seen Saudi Aramco has been listed on the stock exchange, that represents a higher level of responsibility, citizenship and corporate compliance for the organisation, including at the subsidiary level.’

Whose problem?

One reason why organisations appear to be behind the curve on investigatory planning is that it isn’t an area that uniquely lends itself to the legal team. Efforts in this area are likely to require active input from all corners of the business, as well as an ambient level of support from the leadership team.

Indeed, when asked who within their organisation was responsible for designing and maintaining the response plan, answers were split. While the legal team was the most commonly cited department, it ultimately accounted for just 35% of the responses – and just as many reported not having a response plan at all. 13% – the second most common response – said it was currently a multi-departmental effort, and 10% said it was the domain of a dedicated crisis management team.

‘Day by day, the executive team is more conscious of the importance and necessity of the identification, mitigation and follow-up of risks,’ explains Diana Daza, legal director at SGS in Colombia.

‘As a legal team, we are highly involved in daily risk management operations in order to prevent these sort of risks.’

Despite a current lack of ubiquity around which departments are given investigation planning responsibilities, there is a sentiment that this is changing. From interviews with participants in this survey, it seemed a common view that over time, the pre-investigatory planning job is landing more and more with the in-house team.

‘Based on conversations that I have had with peers, it has become quite common that legal teams, in particular the leadership team, are involved in assessing the risk of investigations and prosecutions,’ shares Oliver Jarberg, deputy chief legal and compliance officer and director of integrity & anti-doping at FIFA.

‘I personally believe that it is one of the key aspects – in particular at management level – for the legal and compliance function to be involved with. In particular, in-house legal teams should already be involved at an early stage by the business so as to flag critical operations, transactions, and provide advice and support on measures to be implemented to mitigate legal and compliance risks – including the risk of investigation and prosecution.’

Annual reviews

Another reason that uptake and confidence in organisations’ planning for white collar investigations is subdued might be because there needs to be an ongoing commitment to reviewing and modifying the plan in order for it to stay effective: external risks are changing constantly, while the risk profile of a business will likely change as it expands or contracts into or away from new business units.

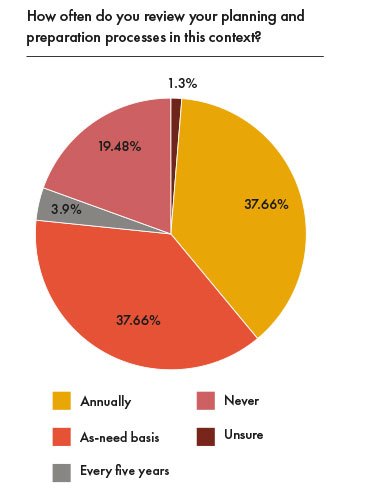

When it comes to reviewing their planning and preparation processes in the context of investigation and white collar prosecution risks, 38% said that they review their process annually, while another 38% reported only conducting such a review on an as-needed basis – another 19% said that they never review their plans in this area.

‘We undertake an annual review and it is critical to understand both the changes in the legal landscape as well as regulators’ approach,’ explains Kwong Wen Wan, group chief corporate officer and group general counsel for Mapletree in Singapore.

Ahmad Ismail is both a proactive participant in his organisation’s investigation preparation, and an avid proponent of conducting regular reviews of any plans or policies.

‘The way I align my plan – especially in relation to anti-bribery and corruption and also in relation to legal and compliance – is that I first understand the company legal risk appetite and then align that to the business cycle of the organisation,’ he says.

‘Clearly, all organisations have their own business planning cycles, and within that business plan cycle you decide on the capital expenditure of the organisation, in other words, what type of investments they are making for the year.’

‘That is normally also mapped against the company’s risk map. So based on that, I will determine what the plan would be for the year in relation to legal compliance. I would analyse that risk map, and get clarification from the auditor and the Chief Financial Officer and the controller. I’d then identify what would be the risk appetite for the organisation, and then I’d map the plan for legal compliance for the year.’

For Jaberg, ‘at FIFA, we have a working group composed of representatives of different professional functions within the organisation, including internal audits, finance, legal and compliance, and different business units.

‘They meet on a regular basis to map FIFA’s main risks and devise strategies and plans so as to mitigate the risks identified within this working group.’

‘I think it is important to establish a formalised risk management process to identify the different risks – including that of investigations and prosecutions – as well as ensuring the processes and measures designed to mitigate such risks are defined, evaluated and implemented. As risks evolve over time, I think it is important that they are reassessed and the processes to address such risks are then amended as required, based on the learnings related to each risk identified. So, in fact, this is a very dynamic task which also requires the legal and compliance function to thoroughly understand the business, the processes and operations of the company.’

‘It’s important to be agile and on top of things, and adapt to the changing circumstances as required to protect the interests at stake.’

Renewed interest from regulators

Give the importance of preparedness for regulatory investigations and white collar prosecutions, why do companies of all sizes and sectors report such vastly different levels of planning in this area?

While the subject may have been on in-house counsel’s radar for many years, many counsel interviewed for this report mentioned a ‘sea change’ in the wake of the global financial crisis, which saw a redoubling of efforts on the part of regulators to rein in inappropriate and illegal conduct, particularly in the financial sector. While a decade is a long time in some respects, in terms of cultural shifts within massive organisations it isn’t very at all, and businesses are still coming to terms with heightened sensitivity on the part of regulators and similar investigatory bodies.

‘It takes time – lots of time – to see real cultural change take hold in a company, or industry,’ says one long-time banking general counsel based in the United Kingdom.

‘There is an increased level of consciousness around white-collar crime which I would say began post-GFC and has continued since then. But unless an organisation has already been stung, it can be difficult to enact change quickly – something I suspect every in-house lawyer will be familiar with. It is on the in-house lawyer to keep their foot on the gas and make sure the company keeps momentum towards compliance.’