Most of you can shut your eyes and easily visualise the moon. You’d be able to ‘see’ the ‘face’, the distinctive features that make our moon so recognisable to us. We all know what the moon looks like. But how often have you looked at the other side of the moon, the ‘dark side’?

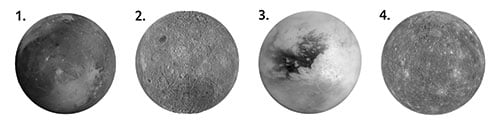

Which of the following images for example is the dark side of our moon?

Exploring the dark side of the moon

Let me share an anecdote with you from a GC I know which illustrates why this may be of importance to you. She and her team were presenting to their CEO during a challenging period in the organisation, and opened with the following line: ‘There is nothing you know about this business that we don’t. Please be assured we understand everything as much as you!’ Expecting praise and a round of applause, they were instead met with silence, then fury. ‘What is the use in telling me what I ALREADY know about this business? I KNOW my own business! What I was hoping to hear from you clowns was what I don’t know about this business!’ Silence fell over the room. ‘Now move along until you can do that!’ The CEO glared at them as they gathered their belongings and left the boardroom.

This was a perfect example of the business looking to learn about what their ‘dark side of the moon’ looked like and what was happening there, only to be let down. It was a lost opportunity where value could have been generated.

I’ve used the dark side of the moon analogy when working with in-house counsel for some time. What part of the business are you always seeing? What parts are others always seeing? What is going on that is part of your business that you just don’t understand? And how valuable, in fact how vital is it, to be shown what you’re not seeing?

The in-house counsel I have met in conversations, meetings or during research fall into two camps: those who have a drive to know what is on the dark side of both their own moon, and the dark side of the organisation’s moon, and those that don’t. With few exceptions, it is the former who are regularly perceived to be delivering more value in their organisations, and can empirically demonstrate how they do so.

This drive, motivation, habit, interest, or whatever you want to call it, which makes some in-house seek to build this insight while others just accept the light side of the moon, comes, in my experience, from the individuals and not the organisation. Barriers to in-house finding out what they don’t know do exist but most of these are inside the heads of in-house. I’ve yet to meet a non-legal stakeholder who tells me that they wish their own in-house team spent less time really getting under the skin of our business. I have met countless who have said the opposite: ‘It’s not me. It’s you.’

But does this really matter? Massively. Because if you want to be taken as someone who has valuable understanding you can either offer insight on matters where you have subject expertise, ie the law, or you can offer that and insight into the organisation. It’s no surprise that those with the greatest influence and impact do both.

Greater impact and insight

Why does this lead to greater impact? As the CEO in the original anecdote knew, someone who can help you see what you are missing is rather valuable; they are a strategic asset. But it goes beyond this ‘consiglieri’ role. An in-house lawyer who has that level of awareness can naturally appreciate how what they are doing connects to the organisation. That understanding can affect what they do and how they do it in fundamentally important ways.

We’ve found repeatedly that in-house lawyers effectively deliver value in a few ways, each offering increased value to the organisation.

The provision of legal services at a lower cost than paying an external lawyer is the least effective way of adding value and really is little more than ‘the price of entry’. It’s what is called a ‘race to the bottom’. And it’s dangerous.

Protecting the margins and adding to the top line

The next value-add activity is connecting the in-house legal enterprise to reductions in organisational loss. In other words, protecting the organisation’s margin. To use an analogy, petrol is only ever a ‘distress’ purchase. We buy it because we have to; without it our cars would not run. The in-house legal team in the first two examples is like that: we buy it because we have to, so let’s find the lowest cost. But what if it added value by making the journey somehow ‘better’? Well, that’s a different proposition altogether.

A more practical and less abstract example? I know an in-house lawyer who needed someone in their team because employee legal matters were a problem. Growing contract disputes, tribunals, and hiring and firing problems had led to a spike in legal costs. Someone was needed to cover this workload and ‘insource’ the work. But carefully hiring someone who would fit in with, and sit with, the HR team for three days a week didn’t just lead to a lower cost for servicing the business activity overhead. By working with the HR team closely, patterns of managerial behaviour emerged and the company was able to implement revisions in performance management processes that didn’t just cut down legal costs, but staffing costs too. That’s adding value.

The final activity we have found is where the legal team can add to the organisation’s ‘top line’ or gross revenue. Via insight into the organisation’s ecosphere, what is happening on the ‘dark side of the moon’ is used by the in-house legal team to support activities that fundamentally affect the business’s growth. Examples could include using a legal compliance position to help create leverage in complex negotiations, so a better price is achieved. Or by guiding contract negotiations in such a way that commercial aims are achieved and supported by the skilful crafting of contract provisions, based on detailed insight into the business model as well as the legal models in play. For example, the default legal model might be a buyer/supplier position when in fact what could be sought is a partnership. The legal team can help the commercial negotiators to see this error of judgement. These are the positives.

The negatives can result from failing to intervene and allowing damaging headlines to appear. When the CEO goes to the press and says: ‘But it is legal’ then my question is: ‘So what?’ followed swiftly by: ‘How did your GC allow you to get into this mess?’ What value to the ‘top line’ sales and the share price could have been saved by a GC who took steps to prevent this scandal? The person who could have made the difference here was the GC. Understanding the dark side of the moon is a vital start to adding more value. You’ll know more, you’ll discuss more and you’ll immediately impact more.

But it is only a start, since you need to equally fully grasp how your services do or don’t add value. What’s your dark side of the moon? How much of your in-house service is like petrol – only ever a distress purchase? And how much is supporting margin reduction or the top line? If you can’t immediately quantify that, how can anyone else?

Finally, who is the person driving all of this activity? At the end, this comes down to you, the general counsel. Not your organisation. So as a final word I’d suggest you be the one to aim for the moon. Sure you might clip the trees, but if you aim for the trees you might never get off the ground. Set your own goals and leave it to others to set your boundaries. Just make sure you don’t always go for the light side: don’t be afraid of the dark.

Discovering the dark side of the moon

- Find out what you and others don’t know about the business. This means being more like Columbo. You will need to be a detective, constantly finding what everyone (including you) has missed.

- Make sure you know which of your services is helping add value or reduce costs. Would you and others automatically know those that are adding value through margin improvement or adding to the ‘top line?’ How could you address this?

- Are the barriers stopping you from adding more value coming from the organisation, or are they coming from you?

- Above, our moon is shown alongside three other celestial bodies. Our moon is number 2, and the others are; Pluto (1), Titan (3) and Mercury (4).