This year marks the 20-year anniversary of HRC’s Corporate Equality Index (CEI), a national benchmarking tool for corporate LGBTQIA+ inclusion in the US. But Latin American countries are fast catching up with their neighbour in the drive for recognition of inclusive professional environments for LGBTQIA+ employees and, in 2016, a Mexican version was launched.

Run by LGBTQIA+ inclusion consultancy ADIL, the HRC Equidad MX: Global Workplace Equality Program promotes LGBTQIA+ equality and inclusion in the Mexican corporate landscape through an annual workplace survey, like its US counterpart. Each year, participating businesses in Mexico offer up their policies and practices for scrutiny, hoping for recognition on a list of ‘Mejores Lugares Para Trabajar LGBTQIA+’ or ‘Best Places to Work for LGBTQIA+ Equality’.

Mexico has a suite of laws prohibiting discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people in areas such as marriage, adoption and more, although these are often state-based and coverage across the country is incomplete. The Out Leadership Business Climate Score gives the country a rating of 7.5 out of 10, marking it ‘low risk’ in three out of four risk categories. However, according to that same index, ‘Pervasive anti-LGBTQIA+ violence and homophobia in Mexico and the patchwork landscape of legislation may create challenges for companies seeking to relocate LGBTQIA+ personnel to Mexico.’

Francisco Robledo Sánchez is a Mexican consultant and strategist in LGBTQIA+ labor inclusion, and founder of ADIL. He explains that culture, practices and the law do not always match, and that it remains important to campaign on LGBTQIA+ rights in the Mexican corporate space.

‘Mexico is a very conservative and Catholic country, where a lot of companies are family companies that have grown into large corporations, or companies that come from different countries with offices here, that don’t have D&I on their radar at all,’ he says.

‘Mexico, is very, very behind on sexual education and diversity and inclusiveness – basic information that’s not taught anywhere in our curriculum and at any stage of public or private education. So, the corporate world has been a great place for re-educating adults in the workplace, so they can positively impact their families and their social circles.’

But the tide is turning, according to Robledo: ‘The interest is genuine, the social pressure is big, there are a lot of ingredients in this conversation, and I can see that people are more comfortable to talk.’

Capitalising on that increased appetite for conversation about LGBTQIA+ inclusion, Equidad MX is on a mission to build workplaces where anyone can be themselves at work, and to celebrate where companies are doing this well.

Eight years ago, Robledo first met with Deena Fidas, director of HRC’s US Workplace Equality Program at that time (the current US director is Keisha Williams, a lawyer, law professor and former in-house counsel). Fidas wanted to help US-headquartered companies expand LGBTQIA+ inclusion in their Mexican operations to provide the same experience for staff working internationally, while also supporting Mexican companies to comply with the supply chain DE&I requirements of US entities. ADIL was selected to run the program, which launched in 2016 and released its first report in 2018.

By 2016, the CEI had been running for 14 years, making it an excellent template for Equidad MX.

‘We reviewed it question by question, and we asked ourselves: “what is a good fit for Mexico right now to ask for as minimum requirements?” We had a couple of roundtables discussing what we should be asking locally. We thought that, for the first five years, we should ask for the very basics,’ Robledo explains.

The team settled on three criteria, or core pillars, of LGBTQIA+ inclusion, which companies seeking to appear in the Equidad MX list need to demonstrate. The first of these is adoption of non-discrimination policies, necessitating a written commitment to encourage eventual standardisation among companies – and nuance is a must. For example, the Mexican constitution bans discrimination due to ‘sexual preferences’, Robledo explains.

‘We knew that companies would only put what the constitution says. But more involved companies would actually know that we should abide by these three big dimensions of sexual diversity and gender and diversity. So first, it was: “let’s ask them to put these terms in writing, particularly sexual orientation and gender identity, and then gender expression as an option for more involved companies.” That’s a basic commitment and we can grow from there,’ Robledo explains.

Alejandra Bogantes, legal manager for Costa Rica and El Salvador, and Bob López, deputy director of culture, diversity and inclusion, Walmart México and Central America

Bob López (BL): This is the fifth year that we have received the certification, certifying that we are a company committed to the LGBTQIA+ community, we respect the LGBTQIA+ community, that we have in place those policies, procedures with regards to talent acquisition, talent development, non-discrimination policies and so on.

Last year, for example, we rolled out our trans associates guidelines, so that here in Walmart we can be ourselves at any time, and we can explore the potential that we may have within the company.

To give an example, at Walmart, you can choose a name on your badge – you either define yourself as a female or male associate. Regardless of your birth certificate, you can choose that name on your email address or on your badge, and we respect that. Here in the region, it’s very complicated for the trans community to officially change official government documentation. But in Walmart, we are not requesting that. If you want to change your name or your email address, we can do it for you, and we respect that.

Alejandra Bogantes (AB): The legal department helps in all new initiatives, for example with the trans gender issue, because the company needs to make policies to make people feel good and so the legal department will help in terms of how we can comply with the law, working with HR.

BL: The HRC Equidad MX report is a real certification process. You need to submit a lot of information to confirm that you are making affirmative actions for the LGBT community, that you have in place policies, trainings and so on, to preserve and enforce a safe workplace for the LGBT community.

And at the end, they do an audit to confirm that you are doing this for your associates, and they give you back a report with feedback, with recommendations on how you can improve your current processes, and that way you can start working on your action plan for the next year. So, it’s adding value to the D&I strategy. It’s been a great journey, because we have been learning a lot from other companies, sharing our experiences in regard to the LGBT community.

The second pillar for candidate companies is the creation of employee resource groups (ERGs) or diversity and inclusion councils. In another example of Equidad MX’s desire to systematize LGBTQIA+ inclusion policies, the idea was to see companies build on and solidify the work done thus far by champions.

‘We found that very, very, very few companies have a diversity and inclusion area or a full-time person responsible for these matters. Some would have a diversity council. So, this part was more of a challenge because we were requesting companies to formalise their commitment by founding a council or building an ERG, or the basis of an affinity group. Because we had a lot of champions. So this was a way of saying, “ok, we have it in writing, now which group of people are going to make it real, are going to transform it into programs and procedures?” – we have to visualize that group of people,’ says Robledo.

The third pillar is engagement in public activities to support LGBTQIA+ inclusion, which means that companies must evidence at least three public activities – and these must take place throughout the year, not only during Pride.

The thread running through the criteria, and the ethos behind Equidad MX, is not just to reward the corporate ecosystem as it relates to workplace LGBTQIA+ equality and inclusion, but to move it forward. The pillars, Robledo explains, are designed to meet companies where they are now – but also to challenge them to move on.

‘It’s just a basis. One of the other missions is to empower companies to tell us where to grow, how to grow, and what’s needed locally, so we can set that as a standard and make this grow together.’

But in moving the conversation around inclusion forward, Robledo has, at times, found the legal profession to be less helpful than he believes it could be. He explains that although there is a federal law banning discrimination based on sexual orientation, it was Mexico City as a state that broke this down into sexual orientation, gender identity, sexual expression and sexual preferences, addressing the specifics of discrimination around characteristics like speech and dress for the first time. But while the federal constitution refers only to ‘sexual preferences’, many companies comply only to that degree.

‘Still today we find a lot of lawyers that still don’t want to make that change, because they say that if the law says “sexual preferences”, then that’s it. And then we say that if we don’t break it down in these terms then the company is not actually being that advanced or that forward. It takes a lot of lobbying for us to make them see how they should keep up with what society and what international laws are saying and not just local laws. It’s a tough group. Sometimes we just have to pull out the Mexico City Constitution (if they are based in Mexico City) and tell them: you’re not abiding by this law and just ignoring it and going to the other law which is incomplete,’ he explains.

‘We have to break down these terms so they can use them in a procedure of a lower scale within the company or just with internal communication. So, they may have still have just “sexual preferences” but then people in the D&I area or champions will find a way to put it in writing in a document of different rank within the company.’

Robledo argues that despite protection under legislation in Mexico, LGBTQIA+ people wishing to bring workplace discrimination claims often find themselves unprotected.

‘The federal law and the local Mexican law don’t have teeth. There’s lots that ends up only becoming recommendations,’ he says.

And, he adds, the lengthy, demanding and resource-intensive nature of the process for pursuing a claim is a disincentive for bringing proceedings in the first place.

‘People are not suing for discrimination in Mexico, so then many lawyers are very comfortable in their positions – “It’s not an issue because we are not losing money, on the reputational side there’s only very few companies that have been exposed to discrimination issues”, and so it’s not a priority for them. The global sense is: “Ok, prove to me you were discriminated against”. But the laws that we have are not that strong, so it can actually be a nicer process for me if I receive the discrimination.’

As long as the laws remain relatively toothless, Robledo believes, addressing workplace discrimination against LGBTQIA+ groups will not be a priority for in-house teams, and policies addressing the issue will remain recommendations. However, engagement among the legal profession is looking up: despite the 2021 Index featuring no law firms at all, the newly released 2022 report includes five.

Speaking with his consultant hat on, Robledo has found that, in many cases, the motivation behind improving LGBTQIA+ inclusion can be an obstacle towards achieving it.

‘We have a few very large Mexican companies that have started to do the D&I work because they have international pressure from customers and clients in other countries, but not coming from a genuine interest. As a consultant, when I ask them why they want to start doing this, almost 80% come from a business perspective: my customers, the stock market in the US is asking us for some sort of documentation, some business or money-based perspective on why they want to do it,’ he says.

Across the global corporate community, the business case for DE&I is often a major argument made for increasing workplace inclusion. But Robledo contends that can be a weak basis, leading to an underestimation of how long it can take to achieve, for example, Equidad MX certification.

There are two types of companies, he says – those with an intrinsic commitment, and those whose commitment is driven by marketing opportunities. But, buoyed by the power of social media, the public is demanding to know what commitments lie behind the Pride flag. The Index itself, says Robledo, can perhaps help such companies develop a more authentic commitment, by serving as a toolkit as well as a commendation:

‘Pride was their only option to show that they were committed, but on the marketing side. Those marketing perspective companies actually now have a reason. Six years ago, we started working with them to get them to this point.’

Since its inception, Equidad MX has seen year-on-year growth. In 2018, 32 companies received the accolade. In 2019, the list had grown to 69, 120 in 2020, 212 in 2021, and the most recent 2022 edition saw 242 companies listed, out of 262 survey applications made. Robledo is pleased, despite having had a goal of 300 applications for the 2022 edition, which may have been stymied by the pandemic. But growth may be slowing, he fears.

‘It’s coming to a maturity point where we’re not growing that much anymore. We now have 262 [applicant] companies and maybe 60% of them were doing it well in another country and they just had to put it in place in Mexico. Maybe another 15% were forced by their global business partners, global customers or clients that were pressuring for them to grow LGBTQIA+ inclusion. And the last group really just want to do the right thing by working on it – maybe they started three or four years ago and finally now in our fifth year they are ready to jump into the report,’ he says.

‘For the rest of the companies, their starting point is lower than 80% of the companies we found five years ago. So the group is going to slow down in the next three, four or five years.’

The focus for the report now is to strengthen the tools that the team is trying to develop, moving the conversation on in Mexico, and lobbying to have impact beyond the corporate sphere and linking the results with legislative and policy changes. The next report will evolve the list of criteria to look at how LGBTQIA+ people are included in employee benefits, as well as training offered by organizations. In addition, the team is looking to branch out beyond Mexico City, where many participating companies are based.

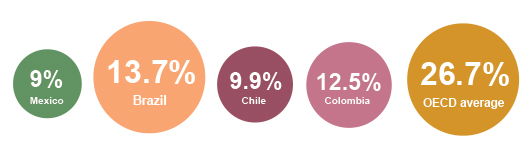

The HRC continues to broaden its reach across Latin America, having launched a similar initiative in Chile two years ago and, recently, in Brazil and Argentina. The team is also looking at Colombia and Costa Rica, where there has been interest.

‘I’ve been looking for partners in each country so they can implement and be the local focal point,’ says Robledo.

‘Maybe down the road we will have a LatAm version of the survey, where we can talk about some general requirements and some local requirements as well.’

Having a diverse team brings different points of view to the table where a specific solution or point is raised because of the unique perspective of an individual based on their life experience and identity. I have been in situations where someone raised a point that was within my blind spot, and without which the group would not have reached its ultimate decision. I also believe that diverse teams have the ability to be more creative and innovative in their way of thinking leading to better decision making overall.

Having a diverse team brings different points of view to the table where a specific solution or point is raised because of the unique perspective of an individual based on their life experience and identity. I have been in situations where someone raised a point that was within my blind spot, and without which the group would not have reached its ultimate decision. I also believe that diverse teams have the ability to be more creative and innovative in their way of thinking leading to better decision making overall.

First, we should make mindful decisions about who we hire and resist the urge to favor people who look like us, went to the same schools as us or grew up in the same towns as us. Then, once you have a diverse legal team, be mindful that everyone’s experiences are different, and just because something has worked well for you, does not mean it will work well for me. Unsolicited commentary about the way one person handled a situation could be received differently than may have been intended so we should be aware of the impact of our words. Allow lawyers to develop their own styles and manage their projects as they see fit as long as the common goal to fulfill a client’s needs is being met.

First, we should make mindful decisions about who we hire and resist the urge to favor people who look like us, went to the same schools as us or grew up in the same towns as us. Then, once you have a diverse legal team, be mindful that everyone’s experiences are different, and just because something has worked well for you, does not mean it will work well for me. Unsolicited commentary about the way one person handled a situation could be received differently than may have been intended so we should be aware of the impact of our words. Allow lawyers to develop their own styles and manage their projects as they see fit as long as the common goal to fulfill a client’s needs is being met.