Global trends in fintech

The digitalisation of finance and the opportunities for fintech

The Covid-19 pandemic disruption has brought a sea of change to the global financial services industry. Firms have had to keep pace with rapid developments in modern digital technologies, as well as grapple with ever-changing consumer expectations and preferences. As we head into 2022, it is expected that the continued rise of the Digital Economy will further reshape the financial services landscape.

The ongoing pandemic has proven to be an extreme stress test for the finance industry which has responded with a wave of innovation. A key driver behind this has been “the great unbundling of financial services”, and its rebundling around a digital infrastructure, to foster the development of an inclusive digital economy and encourage seamless cross-border transactions around the world. This has placed fintech at the heart of the industry. Fuelled by the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties, the prioritisation of sustainability and transition to net zero has further generated new opportunities for fintech solutions to the climate change challenge.

As financial services are unbundled and repackaged around a digital infrastructure, market competition has intensified, with a marked power shift from service providers to consumers. The line between tradfi and fintech has also blurred given that traditional financial services are now embedded on non-financial platforms and financial institutions are becoming digital ecosystem players.

Record levels of fintech investment and funding

The digital shift has also precipitated record levels of investment – including venture capital – into digital assets, payments and fintech generally. By the end of Q3 2021, global fintech funding reached US$94.7billion, almost double the 2020 year total.

Asia is a particular hot spot for fintech deals which reached a record high of 307 deals totaling US$5.9B in Q3 2021. The region has seen consecutive quarterly deal growth since Q2 2020, and funding growth since Q3 2020. Fintech has also been credited with the birth of 200 new unicorns in the first three quarters of 2021.

We expect these trends to continue to accelerate into 2022 and to drive more transformational deals in the fintech space. That said, it remains to be seen if the heat in the market can be sustained as the impact of regulatory efforts, such as the suppression of so-called “killer acquisitions” in tech, antitrust attention on control of data, and new or enhanced foreign investment regimes focused on investments in tech, start to bite.

The global regulatory reset – and its impact on investment

China has implemented a major regulatory reset across financial services, antitrust and data – focusing on some big tech business models and crypto. The China clampdown is impacting domestic investment but also creating opportunities in India and South East Asia particularly Singapore, for growth as a fintech ‘hub’.

The US is also experiencing a reset – regulating by enforcement, with more anti-tech Biden regulatory appointees and changing tides of sentiment against US tech giants. The EU and the UK post Brexit are keen to catch up with their large rivals: focusing on fostering safe and trustworthy innovation, building on more established frameworks and putting out bold new proposals with more to come in 2022.

Blurring lines between crypto and mainstream financial markets

The range and complexity of digital assets continue to expand, with the rapid growth of the DeFi and NFT markets and broadening development of digital assets pegged to traditional assets (so called “stablecoins”). Institutional exposure to digital assets as a distinct asset class is expected to increase significantly while deployment of novel technologies in traditional financial markets gain momentum.

The crossover between decentralised and traditional markets and related contagion risks is becoming a particular concern for policymakers. A key challenge is to determine how policies should evolve to address both novel and traditional market activities deploying novel technology in a manner that fosters innovation while managing risks effectively.

Payments and the future of money

Cross-border payments are also a hot topic, as Asian regulators explore central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) and cross-jurisdictional linkages of real-time payment systems as a means of faster, cheaper, and more inclusive cross-border payments.

The payments industry has boomed during the pandemic but still rests on a patchwork of products and regulatory frameworks globally. Greater harmonisation is needed both in the approach to products and services and in respect of regulation of the industry. One big question is how CBDCs will change the payment markets, both in terms of providing a digital solution to the future of money – where it will be battling it out with stablecoins – and reducing friction in cross-border payments. Regulators are also taking interest in the proliferation of Buy Now Pay Later schemes as part of their central focus on consumer protection.

Data governance, AI and cybersecurity – an increasingly complex matrix

Regulators in major markets are adopting divergent approaches as they seek to strike the right balance between incentivising effective risk management and encouraging innovation. The EU’s first mover proposals for an AI specific regulation have provided a benchmark for a comprehensive, risk-based approach, while the UK is considering deviations from EU standards for both data protection and AI. China has responded to GDPR with a similar, but sometimes more stringent, data protection regime, as well as making its own proposals on global standards for AI. Data protection and cyber rules are proliferating in the US, as well as increasing enforcement against digital platforms.

Several markets are also following the lead of the UK and EU in issuing wide-ranging operational resilience requirements. This broad range of unharmonised international requirements will place increasing pressure on financial institutions to focus resources on the increasingly complex interactions between technology, risk, compliance and procurement functions.

Innovation leading to increasing enforcement and litigation risk

Novel products and services don’t always fit easily into legal frameworks and may pose greater inherent risks (such as volatility, vulnerability to market manipulation and data breach, scams/financial crime). The increase in their uptake has focused regulators even further on mitigating consumer harm. Where provided by start-ups/scale-ups with relatively immature compliance frameworks, there is a recipe for future investigations and litigation.

Regulators’ expectations have heightened in relation to the prevention of financial crime, transparency, and fair processing of personal data. Now, more than ever, there is urgent pressure on firms to act in the interests of the consumer and to be accountable for ESG as well as diversity and inclusion agendas. The risk of civil claims – including class actions – is also increasing due to the availability of litigation funding in many jurisdictions.

Singapore and financial technologies

What do societies do when change is inevitably imposed upon them? What are the ways in which they choose to adapt – or not adapt, as the case may be – to their surroundings? There are endless examples of adaptation behaviours throughout history: mass migrations, change in lifestyle, diet, among others (Dutch land reclamation efforts are an often-used example). For those that choose not to adapt though, all that is left is stagnation or decline. This is not the path that Singapore has resolved to go down.

Singapore’s financial sector now bears witness to the transformative powers of innovation, and shines as a beacon of financial forward-thinking. The bustling island city-state’s fintech story highlights, among other things, how big a role government, and other traditional institutions such as banks, can play even when a tidal wave of technological change is coming to challenge the ways of old. At heart, it is a story of change: of maintaining momentum when others are standing rigidly still, of embracing technology when others remain reticent or sceptical towards innovative solutions. At a time

when most countries cannot seem to decide on how to regulate financial technologies, or, worse still, when countries impose restrictions on new trends and seem to turn inwards, Singapore on the other hand treats their emergence as an opportunity. An opportunity to cement its status as a leading financial hub not only in the wider region, but the world.

Singapore is Southeast Asia’s leading fintech hub. Approximately 40% of fintech companies in Asia are based in Singapore, with the full gamut of fintech products represented in this already established and rapidly growing sector. This is no

accident, and the development of fintech is one of the key pillars the Singapore government has targeted as necessary to achieve the ambitious goal of becoming a “Smart Nation” over the next few years. This programme, launched by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in 2014, envisages the Singapore of the near future as a city-state that is interconnected by technology at every level of daily life, with financial technology playing one of the major roles in this. A key stage of the Smart Nation strategy came in 2016, when the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) published the Singapore Payments Roadmap. An integral pledge as part of this was to create a Smart Financial Centre, where, in the MAS’s own words, ‘innovation is pervasive, and fintech is used widely’. This has been achieved successfully, borne out by the fact that the flagship digital payments service, PayNow, has achieved almost total uptake from its intended audience. The platform, which allows users to make payments effortlessly to businesses or individuals using a mobile number, Singapore NRIC/FIN, or Virtual Payment Address rather than full bank details, is now used by around 90% of active businesses and adult Singapore residents.

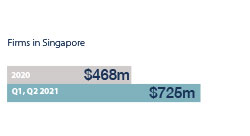

Sensing the opportunities, venture capitalists both overseas and domestic have been ramping up their funding of Singapore-based fintech companies. This dynamic proved remarkably resilient during the Covid-19 pandemic; while funding fell during those opening chaotic weeks, it soon rebounded. Fintech firms in Singapore received US$725m funding in the first half of 2021, significantly more than the US$468m they received throughout the whole of 2020; many companies found increased demand for their products thanks to remote working and a corresponding increased reliance on technology that the pandemic heralded. Clearly investors have confidence in Singapore and its fintech sector and expect it to play a crucial role in the future transformation of the financial landscape.

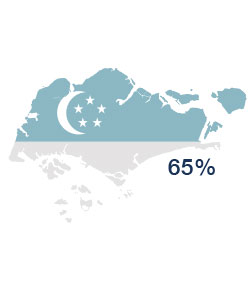

Figures show that this has been the case for some time, and while the pandemic may have caused some panic, it was a matter of when investments returned to Singapore’s fintech community, rather than if. The period between 2015 to 2019 saw around 65% of fintech across the entirety of Southeast Asia land in Singapore.

But it is not just the money that makes Singapore so attractive for start-ups. As a jurisdiction, it is also widely lauded by those who have chosen to operate there, with start-ups and established companies alike praising the city-state for, among other things, its welcoming business culture, a spirit of innovation and ‘East-meets-West’ location and environment. Interviewees who spoke with us during this research project attested to the positive atmosphere in the fintech sector and high morale of those working in it, boosted by regular industry events including November’s Singapore Fintech Festival, the largest of its kind in the world.

An extremely broad-brush term, fintech is, at heart, any sort of digital innovation in the financial sector. While virtually every type of financial software and technology imaginable have found a home in Singapore, there is a definable split between fintech types and how these are represented in Singapore. Research shows that the most popular fintech segment over recent years has been the capital markets and wealth management space, followed by payments, credit, regtech and insurtech outfits. The large variety of more niche providers make up the rest of the pack. In 2021 specifically, digital payments received the highest amount of funding, indicating a shift towards this segment, while cryptocurrency companies made up the greatest number of those to receive funding. Clearly, while cryptocurrencies are of great interest to investors, they are hedging their bets. Matthew Lovatt, Executive Committee member at the Singapore Fintech Association and financial services tax partner at Deloitte Singapore, summed up the situation on the ground in the following terms: ‘The Singapore fintech community covers the full spectrum of stakeholders. There are, for example, software developers and enterprise blockchain developers headquartered locally, right through to digital asset fund managers, payment services providers, decentralised finance, and regtech, wealthtech, and insuretech. There’s a very strong ecosystem in Singapore, which creates an innovative environment and various synergies, and from engaging with the community, it’s clear that stakeholders are attracted to Singapore from all over the world, to establish locally and take up fintech sector jobs. Investors in particular look at Singapore as an enticing investment jurisdiction in the fintech space, given the range of opportunity and activities here’.

Despite the breadth of the sector, general trends that the fintech space is gravitating towards over recent months can be identified. The first is that of interoperability and connectedness in payments, both in terms of different payment services domestically, and interconnectedness with payment services across jurisdictions. For example, in a move that is the first of its kind globally, 2021 saw the linkage of Singapore’s PayNow and Thailand’s PromptPay, real-time retail payment systems. This will allow consumers to transfer funds of up to S$1,000 or THB25,000, daily, across the two countries.

The second trend is that of collaboration, in which state entities, industry bodies, major players in the financial world and fintech start-ups work together to share, test and eventually roll out promising ideas and concepts to the market proper. The 2017 establishment by the MAS of the Payments Council is a fine example of this, in which payment users and providers came together through the council to roll out the SGQR, PayNow and PayNow Corporate payments services.

The third general trend is one of innovation in the areas of embedded finance (the integration of financial services by non-financial companies) and blockchain-based decentralised finance (DeFi). Of the eventual culmination of the work around embedded finance, Jo Yeo, head of the payments development and data connectivity office at the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), explains that ‘Financial services will increasingly be provided invisibly at point of need through non-financial services channels, built on a dense network of APIs – the backbone of the digital economy. Users will place greater value on seamlessness and convenience. Data infrastructure to support data flows is important to support innovation and risk management’. Decentralised finance also has extremely exciting applications, as Yeo outlines: ‘Digitalisation may lead us to a scenario where finance is increasingly decentralised, built on open, resilient, and distributed networks, which accord greater transparency and efficiencies. DeFi has the potential to transform every financial transaction and reach individuals and businesses traditionally excluded from the financial system.’

Leading the pack

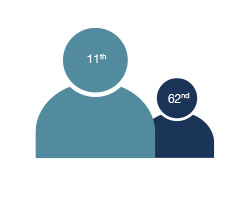

Why has Singapore got it so right? A cursory glance at Singapore compared to its competitors in Southeast Asia would suggest that this is simply due to its level of economic and human development. When excluding the microstate Brunei, Singapore dwarfs its nearest ASEAN competitor Malaysia in both nominal GDP per capita (approximately US$64,000 to US$11,000 as per 2021 IMF data) and by its human development index (Singapore ranks 11th as per the HDI’s 2020 report, while Malaysia comes in at number 62). The arithmetic appears irresistible: higher development and greater wealth means higher salaries, which means a superior calibre of talent will be drawn to the wealthy city-state. Case closed. But this is only a small part of the picture.

Hong Kong, for instance, has been making similar efforts to establish itself as a global centre of fintech innovation but has had notably less impressive results than Singapore. A 2016 report evaluating fintech markets around the world placed Singapore as the fourth best fintech jurisdiction globally based on the benchmarks of talent, capital, policy and demand; Hong Kong placed seventh in the list, despite almost identical funding levels at this point. The follow-up 2020 report indicates that Singapore has pulled away from its main Asian fintech competitor and Singapore is now listed as a ‘core’ global

fintech jurisdiction, alongside the likes of the United Kingdom and the United States, and boasts investment around 36% more than Hong Kong.

So, what are some of the core advantages of Singapore that allow it to thrive at fostering an agile, advanced sector like fintech? Ironically, some of Singapore’s willingness to adapt and embrace technological change could stem from its own colonial past under British rule. But even as similarities between Singapore and Britain today in the context of financial technologies are relevant, Singapore has no doubt forged its own unique path since achieving independence, taking full advantage of its geography, its unique position both as a shipping and trading post, and as an open, welcoming society that embraces diversity. As David Lee Kuo Chuen, professor of finance at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) says, ‘Being a place that really understands both the Western and Eastern culture is a lot easier to do business in – and it’s not a bad place to live for food as well!’ In short, Singapore is a place that understands that combining Eastern and Western cultures can provide dividends in overall quality of life.

Lee believes that it is the groundwork that has been laid over several years, and the progressive outlook of those in charge of growing the business sector in fostering this, is a key factor in Singapore’s fintech success. ‘Digital infrastructure for trade, logistics and other areas has been key in establishing a sovereign digital identity. If a government looks to improve financial technology adoption without owning the digital infrastructure, it ceases to be relevant’, he explains. ‘Singapore’s priority is in building digital infrastructure’. This is just one example of the holistic approach to fintech innovation in Singapore which has characterised it, enabled by a motivated, practical and well-resourced state sector backed up by trusted and effective institutions. One extremely important example of this is the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), which is a uniquely powerful tool at the hands of the government. A complex and multi-faceted organisation, the MAS is both regulator and central bank; and this integration contributes to achieving Singapore’s financial sector strategy, as does the MAS’s function as financial sector promoter and champion. The MAS commonly interacts with industry bodies, including to help contribute and support grass roots-level development. Peiying Chua, a Singapore-based Partner and financial regulatory specialist at Linklaters, commends the MAS as a ‘collaborative and open-minded regulator, who has taken on industry feedback and adjusted their rules in response to their findings.’

In this, it regularly cooperates with other industry bodies to achieve its aims, regularly getting stuck in to building the grassroots of Singapore. ‘We’re very lucky in Singapore to have the MAS as a very proactive and engaged regulator’, says Matthew Lovatt when discussing the Singapore fintech Association’s interactions and collaboration with the MAS. ‘The SFA recently worked with the MAS to develop a payments-specific industry consultation group, to facilitate community engagement and regulatory consultation.’ When commenting on further initiatives, Lovatt noted that, ‘The MAS’s regulatory sandbox (modelled on a UK model) has provided for impactful, real-time interaction with stakeholders from relatively early stages in their development, to identify regulatory challenges and work through them collaboratively in a way that facilitates innovation and development.’ Lovatt believes that to be an excellent example of Singapore’s and the MAS’s desire and commitment to financial services innovation. ‘Traditionally, financial services regulation has been perceived to be paternalistic, and often a barrier to market entry. However, a more principles-based, real-time and proactive approach can not only facilitate financial services innovation and market access, but also equip regulators with what they need to respond to material developments and pervasive new operating models.’ Commenting on the MAS’s wider support and contributions to the sector, Lovatt noted initiatives like APIX, an open architecture API marketplace and sandbox platform to facilitate collaboration between fintechs and financial institutions, and its contribution to support measures, like the fintech Solidity Grant to help Covid-19 affected fintech stakeholders.

The Singapore Fintech Association (SFA) is an excellent example of a non-profit organisation that has had a tangible effect on the sector it looks to promote. Drawing from a cross-industry pool of partners in order to encourage collaboration between everyone holding a stake in the Singapore fintech ecosystem (and beyond, via memoranda of understanding with fintech associations around the world), the SFA has achieved an enviable level of penetration into Singapore’s fintech world. ‘The SFA currently has approximately 900 corporate members and over 1,000 individual members’, says Lovatt. ‘In terms of the spread, our membership spans the entire ecosystem. This has allowed the SFA to play an important role in community growth and development’. A recurring theme in our research was that of the effectiveness and business-centricity of regulation in Singapore, especially on the part of the MAS. Matthew Lovatt commented that under the leadership of its three respective Executive Committees, the Singapore fintech Association has sought to contribute to that. ‘I originally began interacting with stakeholders through the SFA as I found that, during my day-to-day practise in professional services, one of the practical issues frequently encountered was that laws and regulations affecting the fintech space had never been designed to apply to the new types of business models that we were seeing. As such, there can often be some legal and/or regulatory friction which affects operations, and I felt that being part of the SFA meant I could be more active in trying to help address this by working with key people and organisations more proactively’. One of the main ways in which the SFA has sought to do this has been through stakeholder engagement, educational initiatives and through promoting cross-sector collaboration.

The SFA also has a key aim of helping attract talent to Singapore and putting it in touch with the right organisations. ‘Singapore has a relatively small population, which means that access to talent is absolutely key,’ explains Lovatt. ‘This in part means that continued development of Singapore’s fintech sector means attracting talent from across the region and also more widely’. The SFA also seeks to support promising companies’ access to capital as well. ‘We seek to facilitate networking between our members and regional venture capital and investment management associations, through hosting joint events, and also aim to facilitate our members’ access to platforms like the MAS’s Deal Fridays fundraising platform’.

It is by no means the case that the majority of heavy lifting required for the evolution of the Singapore fintech scene has come from non-profits, though. Governmental schemes aimed at assisting the fintech entrepreneurs to get set up in Singapore have been well-received by those on the ground. Founded in 2018, Merkle Science is a predictive cryptocurrency risk and intelligence platform that has found success in Singapore. Associate director and founding member Ian Lee spoke highly of his own firm’s experiences with state-sponsored schemes. As he explains, these can make Singapore a far more comfortable jurisdiction to get set up and start trading in than many others. ‘As you might guess, if you’re a start-up that wants to offer financial products, you have to pay a lot of money for all kinds of compliance services in order to operate in a given market. This is one of the main barriers to entry. And the wonderful thing is that the Singapore government has offered a lot of grants that go a long way in offsetting that. In the case I mentioned, where compliance costs are becoming expensive, you could take a digital acceleration grant, which allows you to claim up to $120,000 for any digital services subscribed to, including compliance software’.

Lee also commends the sheer variety of help available to up-and-coming tech entrepreneurs, especially of those which put them in touch with contemporaries and established financial operators. ‘There are a lot of government-led incubators and sandboxes in which established institutions, major banks, law firms and the like, will be involved and will network with the up-and-coming fintech firms. It’s a terrific way for companies to get started with relatively minimal risk. My company Merkle Science started out via one of these incubators, which are so valuable for the way in which they bring entrepreneurs together with potential funding sources’. For Lee, it is the range of options available for prospective fintechs that sets Singapore apart in the region, with so many options available that anyone with a promising idea can find the right fit for them. ‘All in all, it’s not just the government grants but the incubators, the sandboxes and other networking opportunities that have created space for founders to get their businesses off the ground at relatively low cost’.

And it is not just getting these firms off the ground that Singapore excels at; through the MAS, it looks after its fintech ecosystem as well. April 2020 saw a $125m support package launched to mitigate the most negative effects of the pandemic, and to place the sector in the best possible position to recover and return to growth. As we have seen, with the record funding levels achieved by Singapore’s fintech sector in the first half of 2021, this has paid dividends.

A regulator with a difference – The MAS in focus

The understanding and business-friendly nature of regulation in the fintech sector in Singapore is one of the most well-liked aspects of operating there. As sole regulator, the MAS can take much of the credit for this positive state of affairs, and is an institution that is mentioned time and again both by industry observers and those we spoke to in this report as being perhaps the major factor in Singapore’s fintech success. Mark Hwang, former head of legal and compliance at ARA Asset Management (since this interview, Hwang has now moved on to be group head of legal for ESR), for instance, credited the rapid expansion of Singapore’s fintech scene to ‘the very commercial minded and open environment that the MAS has created’. So, what makes it so special?

development and data connectivity office | Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS)

One answer is that, alongside its primary roles as regulator and central bank, the MAS also works closely with major players in the financial sector both at home and abroad, to champion Singapore as a financial sector, and looks to

up-skill the capabilities of those within the industry. Of course, fintech innovation features heavily within this demanding brief.

Jo Yeo speaks about the challenges the MAS faces in ensuring compliance with the 2019 Payment Services Act (PS Act) when it comes to fintech start-ups. ‘Licensees that transitioned from the old regime to the Payment Services Act generally have a good grasp of the MAS’s expectations, and can more quickly get up to speed since they are used to being regulated. But, we can see from applications that there is a varying level of understanding of the PS Act’. An example of this can be seen from the fact that 18% of prospective digital payment token service providers withdrew or had their application refused after engaging with the MAS. ‘MAS will only grant licences to those which are able to meet our regulatory requirements including ones concerning anti-money laundering and combating financial terrorism’, says Yeo.

With that said, MAS is making significant efforts working with the financial industry to level up compliance and regulatory standards in the payments sector. ‘One example is the formation of the Payments Group in association with the Singapore fintech Association (SFA)’, Yeo explains. ‘This comprises payments institutions from across the value chain, and the objective is to create a community in payments in which they can share best practices with each other and feedback to MAS on common regulatory issues. The Payments Council is also another avenue where we build partnerships to address issues in the industry to safeguard e-payments. For instance, in this forum the MAS is working with the industry to establish a framework to provide greater clarity on the responsibilities and liabilities of financial institutions and customers in the case of fraudulent payment transactions’.

Another much-heralded initiative spearheaded by the MAS aimed at growing Singapore’s fintech scene culminated in December 2020 with the announcement that four institutions had been awarded Digital Banking Licences. This programme, launched in 2019, planned to allow non-financial players such as technology and e-commerce companies to offer banking services. Eligible applicants were assessed on the value proposition of their business models, their ability to manage a prudent and sustainable digital banking business, and their growth prospects and other contributions to Singapore’s financial centre.

Criteria were applied stringently. The MAS’s original announcement made provisions for two digital full bank (DFB) licences and three digital wholesale bank (DWB) licences; in the event only two DFBs and two DWBs were awarded. As for future plans for further digital banking licences, Yeo is clear that the books are closed for the moment, but this may change in the future: ‘In the immediate term, our focus is on the operations of the new digital banks. We are currently not reviewing any applications for additional digital bank licences. As the digital wholesale banks were introduced as a pilot, we will review whether to grant more DWB licences in the future, once we have reviewed the effects of the current batch, which are expected to begin operations in 2022’.

But the MAS is looking forward even further than this. It launched Project Ubin in 2016, a collaborative program in which Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) were examined for their potential use in clearing and settlement of payments and securities. This five-stage plan which concluded in 2020 saw the MAS partner with the largest banks and financial institutions in the country including BAML, Credit Suisse and HSBC, as well as the Bank of England and Bank of Canada.

Clearly, the project was a wide-ranging one, and the resources and expertise expended on it have further cemented Singapore’s status as one of the main fintech innovators worldwide. Describing Project Ubin as a ‘resounding success’ on its own terms, Yeo nevertheless sees Project Ubin as necessary for the establishment of truly game-changing payment systems: ‘After five

phases, including studying trade-offs, advantages and limitations, MAS has issued accompanying reports and source codes covering everything from design to use-cases, and has amassed a great deal of invaluable data and experience. The learnings from the experiment have allowed the industry to build upon the work of Ubin and advance towards production grade implementation’.

As a catalyst for change, Project Ubin is already bearing fruit. State investment firm Temasek has partnered with JP Morgan and DBS to build on the findings of the project and establish a company called Partior to provide better FX, multi-currency settlement processes across borders. ‘The experiment has provided a sound foundation to accelerate plans for this exciting endeavour’, says Yeo.

The MAS is a uniquely valuable tool in the creation and maintenance of Singapore’s first-class financial infrastructure. As combination central bank and regulator, it combines the two most important national financial functions under one roof, making it a dominant force in the Singapore financial scene. This, along with a steadfast desire to shape and build the finance sector – and cooperate with partners in doing so – makes it a crucial factor in Singapore’s success in nurturing fintech.

The regulator’s commitment to enabling new forms of business is not unlimited, however. January 2022 saw the MAS issues guidelines on cryptocurrencies (or Digital Payment Token (DPT) Services as they are known in the Payment Services Act 2019). The aim of the guidelines, in short, is to discourage cryptocurrency trading among the general public, in order to shield them from the perceived high risk that such activity entails.

Among other precepts, these new rules limit cryptocurrency trading service providers from promoting their services to the general public. In practice, this means that DPT Service Providers will be unable to advertise in public areas such as on public transport or on social media platforms, and will limit the behaviour of third parties such as social media influencers to promote DPT services. Cryptocurrency traders will only be able to market or advertise on their own corporate websites, mobile applications or official social media accounts.

At the very least, the MAS has taken the position that cryptocurrency trading is risky enough that the general public should be shielded from anything that might convince them to engage with it, which is a shock to DPT Service Providers that may previously have felt Singapore would be at the vanguard of the financial revolution. How much this will affect new startups from entering the Singapore fintech ecosystem remains to be seen.

Cryptocurrencies: A brief overview

‘Singapore has been building its status as a cryptocurrency technology hub, which forms the backbone for a number of financial activities. And the MAS is of the view that, while there is a place for cryptocurrency in Singapore, it should be subject to appropriate regulation’, says Chua. One of the most high-profile developments in financial technology, and one that even excites laypeople for its truly transformative potential, cryptocurrencies are one of the fastest growing sectors of Singapore’s fintech scene, achieving large investments from a variety of sources. But how do they work, and what are some of the main ways they can disrupt the established financial order?

Simply put, cryptocurrencies are digital currencies that can be securely exchanged online for goods and services. There is a substantial number of cryptocurrencies today, and their number is growing as companies and individuals seek to develop their own. The most well-known examples of cryptocurrencies currently are Bitcoin and Ethereum, and these are by far the most established and the most valuable.

Generally speaking, the value of cryptocurrencies is volatile and fluctuates at a pace that leaves many investors uncomfortable. For example, in November 2021, the value of Bitcoin reached stratospheric levels, its highest ever, only to come crashing down a few days later as people sought to cash out straight away. However, as a general trend, the number of businesses worldwide that accept them as legitimate forms of payment keeps increasing. They are now accepted as legitimate payment not only in internet companies such as Wikipedia and Microsoft, but also brick-and-mortar outlets such as Burger King, Subway and KFC.

Since we are dealing with digital assets that hold no value in the analogue world, it is important to look into what gives cryptocurrencies their value and how they are generated. In order to do that, we have to look into what technologies make cryptocurrencies possible in the first place. For anyone wanting to learn more about cryptocurrencies today, one of the very first things they are bound to come across – besides of course stories from people who “made it big” by investing in cryptocurrencies early on – are terms such as DLT and blockchain. So what are DLTs, and what is blockchain?

Making cryptocurrencies possible: DLT technologies and blockchain

Invariably, cryptocurrencies rely on blockchain technology, which is a form of digital archiving that effectively keeps track of all transactions – a currency wouldn’t hold any value unless everyone can agree on how many coins there are around. A quick way to visualise a ledger might be something akin to a giant excel sheet, multiple identical copies of which exist in every single computer that deals with cryptocurrencies. We will examine how this works in more detail below, but one of the first things to note is that it makes fraud exceedingly difficult, or even near impossible. This is because computers communicate with each other in a way that is, for all intents and purposes, instantaneous. Discrepancies between a copy of the ledger in one computer and different copies in every other machine would make cases of fraud apparent. This decentralised database is referred to as Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) and is the first element in a structure that allows things like cryptocurrencies to emerge. Without DLTs, cryptocurrencies in their current form would not be possible.

Blockchain is one type of DLT – again, a distributed ledger that exists simultaneously in multiple computers running the same software – which updates data in “blocks” (a list of data, in this case transactions), and a string of “blocks” form a “chain” (a stack of blocks of data that is updated serially over time). Therefore, any information about a potential transaction gets implanted into the blockchain (this series of data) that is stored simultaneously on many different computers, so that it becomes exceedingly difficult for anyone to fabricate transactions that did not take place. The process plays out like this: each transaction is “packaged up” online as a block, then that block is communicated to the entirety of the network. Then, the network will either approve or decline the transaction (in case of anomalies). If approved, the block will get added to the tail end of the blockchain, and will become forever embedded in the history of transactions.

We have seen the underlying structures that allow cryptocurrencies to form. The important thing to note before we go into more detail is that blockchains have no central administrator. The ledger does not actually “belong” to any single user, nor can any single user make unwarranted changes to the blockchain on their own, since identical copies of the ledger exist in multiple computers. Once something has been “locked in” in the chain, it is almost impossible to change. This reliable form of decentralised structure is called a “peer-to-peer” (or P2P) network. As David Lee of SUSS says, ‘Cryptocurrency brings to the mind of governments, corporations, and the community that it is the peer-to-peer exchange of value that is important, as is peer-to-peer communication and messaging. The fourth industrial revolution is all about peer-to-peer communication and value exchange’.

It is only possible to develop these groundbreaking technologies, or “the fourth industrial revolution” as Lee calls them, at places where there is a free exchange of information and ideas. Where ideas are allowed to form and be communicated freely, invariably they will be refined and allowed to grow.

Benefits of cryptocurrencies and the role of Singapore

That explains the underlying structure of blockchains, but what is so special about cryptocurrencies in the first place? What are the benefits of cryptocurrencies over conventional currencies? In short, cryptocurrencies allow users to bypass traditional institutions, such as banks, that may be adding barriers to transactions. For example, the simple act of transferring £10 to an account belonging to someone overseas would involve two different banks and a clearing house, all of which is time-consuming and can potentially incur extra charges. Cryptocurrencies allow users to go around these barriers and transact with each other with no time delays or extra charges.

A common misconception around cryptocurrencies is that they are anonymous and untraceable. As Ian Lee of Merkle Science explains, this is not the case: ‘Crypto is not untraceable. While I do want to caveat that by saying that there are some privacy blockchains available that are designed to be

untraceable, most of the blockchains out there, like Bitcoin or Ethereum, are traceable. In fact, these are blockchains where every single transaction that a person does is publicly recorded and anybody can analyse. For many years, when people first heard about crypto, there was a misconception that crypto is not just untraceable but also anonymous. And, strictly speaking, that’s not true. Cryptocurrencies are not anonymous. In fact, it’s what we call pseudo-anonymous. Anonymous means that you have totally no idea who’s doing it and there’s no way for you to find any links to who is responsible. Pseudo-anonymous, means that, while you might not be able to tell which person an account belongs to initially, you can monitor that account and see multiple transactions which, along with external information, allows us to try and identify the individual behind the transactions’.

Not only that, but blockchain allows for much more in-depth analyses of public databases. In essence, all this information about transactions is, by its very definition, part of the blockchain, which can never be removed from public view. This readily available information can play a crucial role in many areas of public life, such as combating crime in the real world. Ian Lee expands on this: ‘When analysing public databases, we have teams that build a log of addresses which are linked to, let’s say, terrorist organizations, darknet addresses or scam exchanges. We leverage on this, so that whenever transactions are being conducted that appear to be malicious, we can go onto the blockchain and let them know that funds are coming from an address which we know is linked to a particular criminal organisation or entity’. In fact, blockchain-based currencies are a potential boon for security services trying to build a case against malicious actors. ‘In the traditional transaction monitoring space, where you might go into a bank and deposit funds from, for example, wallet

A to wallet B, the bank would only know that your funds in wallet B came from wallet A. Whereas with blockchain, when a deposit is being done, not only can we see that wallet A sent funds to B, we can see that B sent funds to C, C sent funds to D and so on. So, it’s really bringing transaction monitoring to the next level, where you’re not just limited to analysing direct counterparties, you can go as far back as you want. The example that I always give people is this: Bitcoin has been around for ten years, and because of that we can tell you every single Bitcoin in existence, where they are currently sitting, and who’s held them throughout those ten years. We can see your trail’.

The role of state-issued digital currencies and the Monetary Authority of Singapore

One of the defining characteristics of cryptocurrencies is that they rely on blockchain, which ensures an exceptionally reliable, almost completely hack-proof, way of operating. One of the other unique characteristics of cryptocurrencies is the decentralised nature of the blockchain on which they rely, which means that it is nigh-on impossible for individuals to change the balance sheets. That is because blockchain relies on a consensus of what the history of transactions is, and as we have seen, once a block of transactions becomes a part of the permanent record, it cannot be altered. This provides a lot of trust in the system, as people who invest in cryptocurrencies relying on blockchain have the necessary minimum level of assurance without which all currencies, digital or not, become worthless.

The security and level of trust of digital currencies have opened the window for traditional, centralised institutions to get in on the act. Central banks and monetary authorities around the world seem to be coming around to the simple reality that they risk being left behind or, worse still, slipping into irrelevancy. For those central banks and authorities interested in issuing digital currencies, and it should be noted that the number by no means includes all of them, the answer seems simple: use the existing blockchain technology to issue digital versions of fiat currencies already in circulation. Those digital versions are called Central Bank Digital Currencies, or CBDCs for short.

We have seen that digital currencies rely on DLTs which are decentralised. So how would a decentralised system like DLTs work with a central regulatory authority? The idea is that central banks would issue CBDCs using private blockchain technology so that they get the best of both worlds: the security that blockchain systems provide, but also the ability to control the overall supply of the CBDCs, similar to the way those institutions would control the supply of physical currencies as well.

This means that CBDCs would not only enjoy the benefits of other cryptocurrencies, such as easy, fast, secure international transactions, as well as provide vital information on transactions that would in turn limit or curb activities such as money-laundering (due to the information the database would be able to provide), but crucially would prevent some of the volatility that plagues many digital currencies, such as Bitcoin. This provides a real incentive to governments and monetary authorities worldwide, and some central banks have already issued their digital versions of physical currencies.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore is experimenting with a CBDC version of the Singapore Dollar, while other monetary authorities, such as the Bank of England, have yet to decide on whether to issue their own CBDCs. This gives the MAS a potentially pivotal head-start as an organisation that recognises the value of being a key player in the financial landscape of the future. SUSS’s David Lee highlights the importance of peer-to-peer communication in designing a truly practical CBDC: ‘If there’s anything that authorities in Singapore, China and Europe all agree on, it is that you cannot have corporations dictating to government, as once you have corporations above the government, they will lose their tax revenue and monetary policy. Hence the appetite for CBDCs. Peer-to-peer communication and a peer-to-peer exchange of value is accepted by the government in the design of their CBDCs, as are all the other techniques used in Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies including offline communications and unspent transaction output analysis. That’s the well-designed ones, anyway. For cross-border transactions, what is needed is a multiple Central Bank Digital Currency, or M-CBDC, which harmonises different nations’ systems. ‘But’, Lee goes on, ‘multiple CBDCs work well using a distributed ledger, which potentially comes with all sorts of privacy protections, censorship, resistance and so on. In Europe, there is a resistance to this, which means there cannot be collaboration efficiency between traditional institutions and the new payment companies. In the case of multiple CBDCs, it doesn’t matter whether you are a bank, an insurance company, or a start-up, everyone is welcome to join the CBDC network. That is the main difference – innovation comes and peer-to-peer exchange of information through communication’. This is one area in

which Asia, and Singapore in particular, has shown itself to

be ahead of the curve.

November 2021 saw the announcement of retail CBDC initiative Project Orchid to build the technology infrastructure and technical competencies necessary to issue a digital Singapore dollar should Singapore decide to do so in future. In addition to this, a cross-border payment test, dubbed Project Dunbar, will research the creation of an M-CBDC payments network with South Africa, Singapore, Malaysia, and Australia. Project Bakong of Cambodia, a pseudo-CBDC as it is not a liability on the balance sheet of the central bank, has been successful in corporate inclusion using a blockchain architecture.

Artificial intelligence

The term Artificial Intelligence (AI) still conjures up notions of high science fiction, so much so that it is easy to overlook the truly transformative effects that AI has had on the finance world already, to say nothing of the developments currently in the planning stage and yet to be rolled out. Facial recognition software and chatbots are some technologies that banking customers and other financial service consumers will be familiar with, but behind the scenes the novel use of AI-powered data analytics has revolutionised such areas as risk analysis and the evaluation of insurance claims.

Executive committee member | Singapore Fintech Association

With that said, AI is somewhat of a double-edged sword, and some concerns regarding fraud and privacy risks are causing sleepless nights for compliance teams at large and small financial institutions alike: ‘There’s a constant struggle between criminals using AI for criminal activities or other illegal purposes and real people trying to protect their privacy. The use of AI and machine learning means that it is now possible to generate videos and images that appear to be of real people. That is very interesting – you can generate a human who has never existed. If you’re not sure whether an image or a person is fake, and if it is trivially easy for criminals to create a fake address and photos, then that makes the job of compliance extremely difficult’, says David Lee of SUSS. To fight cutting-edge AI used by criminals, then, what is needed is a robust response from AI-fuelled compliance platforms. Fortunately, many such fintech outfits are dedicated to exactly this purpose, with concepts such as artificial neural networks and deep-learning models being deployed to the Anti-Money Laundering and anti-terrorist financing initiatives. As the pandemic leads to a greater emphasis on digital versus in-person communication, this dynamic has the potential to crystallise into a real and present threat to all financial service users, especially in the metaverse.

But increased use of AI by financial institutions also brings up profound ethical questions around privacy issues. Consider its potential applications in the health insurance world. ‘AI is extremely good at scanning the data to pick up certain patterns that you can use to achieve your goals – pattern recognition for clustering, or classification, or other tracking methods’, says Lee. ‘Given the power of this technology, it would be useful for an insurance company to know everything about you from a health standpoint – life expectancy, medical records, things like that – before they show you pricings or insurance products. It might mean giving up personal data to get the best insurance, or might make it even harder for people with underlying health conditions to get insurance coverage’. As this technology becomes more widespread, it becomes more likely that it could be used for nefarious ends.

It can also be a powerful tool for law enforcement as well, as Peiying Chua explains. ‘Regulators have been using network analysis techniques to supplement the data collected from financial institutions and intelligence from law enforcement, which has helped them to identify networks of suspicious activity across the entire financial sector. They continue to work on adding transaction information to this data set. They have also launched a national program to deepen AI capabilities in financial services and are currently consulting on introducing a regulatory framework and secure digital platform for financial institutions to share risk information with each other to prevent money laundering and terrorism financing’.

Citizens of Singapore or other developed nations are fortunate. Their government is a well-trusted one by global standards and there is confidence in its institutions, but that is not the case in most of the world. Regardless, Singapore regulators must stay watchful of developments in AI, lest they inadvertently create a situation in which civil liberties and the sanctity of personal data become threatened or hacked.

Fintech in the in-house legal world

If we move away from the theoretical side and return to terra firma to see how in-house lawyers are using financial technology at the coalface, a complex picture becomes apparent. Lisa Mather, via her previous vice president, legal and business affairs position at PayPal (since this interview, Mather has now moved on to be general counsel of Mars Wrigley), was at the forefront of payments technology in Singapore: ‘The first thing to say, which is a general point about the ASEAN region, is that you really cannot underestimate the pace at which new technologies and technological offerings are being adopted. It is now so rapid that making sure you stay up to date with the latest developments is a key challenge, especially as the pandemic undoubtedly accelerated digitisation for businesses and the adoption of new digital offerings.’ From Mather’s perspective, it means that every day – and every client – is different: ‘We may be dealing with organisations which are digitising payments to expand their online or their mobile business, but within that every partner is different. While we have certain agreements with templates and boilerplate clauses there will always be customer preferences and business objectives; we want to make sure that we are always as customer centric and frictionless as possible. As we continue to partner with new customers around the globe, we are involved in a complex and evolving ecosystem that, nevertheless, has many exciting new business opportunities that are yet untapped.’

and compliance | ARA Asset Management

Mark Hwang’s ARA Asset Management (ARA) was recently acquired for US$5.2bn by logistics real estate platform ESR in a move which will create Asia Pacific’s largest real estate and real asset manager and the third largest listed real estate asset manager in the world. He shared that ARA invested in Singapore digital investment platform Minterest in early 2020, which merged with licensed digital asset exchange Digiassets Exchange (SDAX) in September 2021 to create SDAX Financial Group. Hwang explains that combining these two entities to form a digital distribution and trading platform has major benefits: ‘One of the main ideas behind combining Minterest and SDAX is to give the investors liquidity in the investments that they make through Minterest. Previously, there was no secondary market in Minterest products and investors simply had to hold their investments to maturity, in some cases for as long as 18 to 24 months. Now, Minterest has the ability to take the loans, equity and debt instruments it originates, tokenise them and list them on the SDAX Digital Asset Exchange, which creates potential liquidity for investors’. This episode provides an instructive demonstration of how cutting-edge fintech developments can open up entirely new avenues for established companies to expand into. In this case, it can potentially allow a whole new class of investors to work with ARA.

‘When we look back at why ARA invested into Minterest in the first place’, says Hwang, ‘what we’ve achieved so far validates the original thesis that Minterest would help us to create new products and reach new classes of investors. ARA’s traditional investor base comprises pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, insurance firms and other institutional investors. Access to new sources of capital, such as high net worth individuals and affluent retail investors, was significantly enhanced through Minterest, and the addition of the SDAX Digital Assets Exchange enabled secondary trading and liquidity’.

Hwang is bullish about the prospects of fintech advancements to rapidly revolutionise the way even legacy financial institutions operate, but he is under no misapprehensions about ARA being the only player in the sector to appreciate the opportunities offered by technological developments, such as the digitalisation of assets: ‘I don’t know which of our peers are also exploring how fintech can benefit their businesses, but this is not a secret known only to a select few. I recently read commentary that Wall Street will be fully tokenised in five years. While you can quibble about the timeframe of that prediction, the point it illustrates is just how much interest and excitement there is around tokenisation. If you think about it, there’s no reason why any asset class cannot be tokenised’.

Kwong Weng Wan, group chief corporate officer and group general counsel of real estate developer-fund manager Mapletree Investments, is clear that their projects now have to be capable of handling the digital revolution which everyone is aware is currently in progress. ‘When we look at new target buildings, we do a lot of due diligence into whether they are future proof in terms of service – are there sufficient server rooms and so on, because that would allow us to market the building more effectively’. As well as this, Wan spoke highly of the level of financial technology adoption by the general population. ‘The adoption rate for the use of electronic payments is very advanced. When you look at the variety of ride-hailing services, and how rare it is to buy from the supermarket or in a restaurant without using relatively new financial technology this becomes clear. PayNow is a highly simplified and practical payment method – you just need to know the mobile phone number or unique entity number of whoever you’re paying or scan a QR Code which does away with having to know the bank account details of whoever you’re paying. It’s used by virtually everyone in Singapore’.

The long and short of it

We have made the case over the course of this report that the Singapore fintech scene has a great deal of strengths which not only set it apart from its regional rivals, but provide it with a level of resilience that was amply demonstrated by the impressive bounceback in investment it achieved following the Covid-19 pandemic in the first half of 2021.

Singapore’s fundamental strengths as a place to do business are often noted, and include its high human development index, a generally wealthy and well-educated population, ‘East-meets-West’ business culture along with high English proficiency, and its non-partisan business innovation-friendly politics. Specifically in relation to the fintech market, Singapore has had several factors which have contributed to its success. The first of these to mention would be the MAS, which has shown itself to be highly effective in growing and maintaining Singapore’s fintech ecosystem. Part regulator, part central bank, it allows for a truly harmonious application of the government’s long-term strategy for building financial technology in Singapore, in line with its Smart Nation plans. Contributors roundly praised the MAS for its efforts and foresight, especially in getting established financial institutions on board with helping fintech companies through sandboxes and other initiatives, and for taking the best ideas from other successful fintech jurisdictions around the world and applying them to Singapore. Throughout this, industry bodies, like the Singapore Fintech Association, have helped to marshal the troops and build a strong network throughout the entire fintech ecosystem. Having a roadmap managed from the top that takes into account the advice of those at the grassroots has allowed Singaporean fintech to thrive, and a strong foundation for future development has also been laid.

So, the prognosis for Singaporean fintech is rosy. But that is not to say that there are no weaknesses to be mindful of, or even threats to take into account. At the macro level, while Singapore’s population is tailor-made to thrive in an advanced economy, it simply is not as large as most of its other main fintech competitors on the world stage, and must rely on other nations to supply much of the talent. This means that it is at the mercy of wider geopolitical events to a greater extent than some of its rivals. While its non-partisan political environment and good diplomatic relations with most nations mean its exposure is as minimal as possible, regional conflicts or crises could lead to this talent pool drying up abruptly.

While Singapore has made a highly promising head-start, new challengers are desperate to take some of the fintech market share away from it. The Gulf states, while in the opening stages of their fintech journey, have huge potential to disrupt the sector, given their vast wealth and appetite for grand projects. The Middle East is already one to watch in the fintech space, and predictions are that over 800 fintech companies will find a home there by 2022, but it is just one example of up-and-coming regions that may look to undercut Singapore in order to steal market share.

The best course to mitigate some of these threats is to maximise the positive aspects of Singapore as a jurisdiction. The laissez-faire but sensible regulatory regime and policies that Singapore is famous for must be preserved and perhaps even expanded on in the future. The most common request from those we spoke to in the report was that regulations be relaxed further to allow new businesses opportunities. This could certainly be a consideration, but it is a double-edged sword. Fly too close to the sun with relaxing regulation and it could lead to untoward business practices or economic issues – the worst possible outcome for a nation that trades on its good governance. Stick to the core competences of what makes Singapore so respected worldwide as a place of business, and the fintech space should be set to continue its progress towards being the number one global financial technology centre.