It’s been a truism of the business world that protecting your intellectual property (IP) is an important part of success since the first laws on copyright were inked in the early 18th century. IP has not suddenly emerged as a key to a company’s long-term prospects. But, undoubtedly, numerous forces have emerged in recent years that have driven companies to more carefully consider how they protect, enforce and monetise their IP. Whether talking about the world of ‘hard’ IP, ie patents, or the ‘soft’ areas – trade marks, copyright and designs – the IP landscape has never been so dynamic or high impact.

Technology, be it in a smartphone or in the formula for the latest blockbuster drug is moving increasingly rapidly. Media continues to disaggregate across multiple platforms, accessible – legally or illegally – at the touch of a button. And at the same time, new geographical markets are opening up, presenting more business opportunities but also greater challenges in protecting IP rights such as trade marks.

You only have to look at the seemingly endless smartphone patent court battles between Samsung and Apple, played out tactically around the world, to appreciate the lengths to which some companies are prepared to go to protect their most valuable assets. Or consider the highly energised debates around attempts to toughen anti-piracy laws in a number of countries.

To assess the legal, policy and business drivers that are shaping the IP world, Legal Business has teamed up with Bristows to survey the in-house community and gauge its feelings on this fast-moving area of law. We canvassed the opinions of a number of in-house lawyers to get their insight into a range of issues affecting their approach to IP in their businesses, gathering responses from more than 200 senior clients. We also looked more closely at the debates surrounding efforts to strengthen anti-piracy laws across a range of jurisdictions and we identified some of the key cases that are shaping IP law in the UK and Europe.

‘In the past, IP issues may have been dealt with by a guy in the backroom, but now they’re at the forefront of a company’s thinking,’ says Bristows IP litigation partner Myles Jelf. ‘If you’re not on top of those issues, an awful lot of value can be lost very quickly.’

TWO TRIBES – THE BATTLE BETWEEN WEB LIBERTARIANS AND RIGHTS HOLDERS RAGES ON

It is perhaps not surprising for an area of the law which has such a profound impact on creative industries that the global battle around strengthening the laws of copyright and beefing up anti-piracy measures should resemble a never-ending Hollywood saga. Like an international espionage thriller, it is being played out across numerous borders. And like the best blockbuster, it is characterised, in some quarters, by a classic good-versus-evil narrative.

In one corner you have the main producers of content – the film and television studios and music companies – that want to toughen laws around illegal streaming and downloading from sites like The Pirate Bay. They would like more of the burden on who polices large parts of the internet thrown onto the middlemen – the search engines and internet service providers (ISPs). And they would like far tougher penalties for the most serious infringers.

In the other corner you have a disparate group of organisations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Reporters Without Borders, self-styled hacktivists and particularly vocal members of the public, who rail against what they perceive to be an attempt to exert control over the internet and increase censorship. Patent enforcement may rack up the largest legal fees, but it’s on the soft side that the most vocal IP activists lie.

In the US, this fight came to a head most recently over two pieces of legislation. The Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and Preventing Real Online Threats to Economic Creativity and Theft of Intellectual Property Act (thankfully shortened to PROTECT IP or PIPA), brought in the US House of Representatives and Senate respectively, were designed to strengthen anti-piracy laws. They placed greater onus on search engines and internet service providers (ISPs) to block access to foreign sites that carry pirated material. SOPA would also have made it a criminal offence to stream pirated material with a maximum jail term of five years for the most serious infringers.

Both were met with passionate opposition from the likes of human rights groups the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Human Rights Watch and Reporters Without Borders. In January 2012 a group of the internet’s most popular sites, including Wikipedia and Google, demonstrated their opposition to the two bills. Google blacked out the doodle on its homepage to emphasise what was viewed as the two bills’ attempts to increase censorship, while Wikipedia staged a blackout with the English-language version taken offline for 24 hours. Within days of the protests, both SOPA and PIPA had been shelved.

As both failed, attention switched to Europe and opposition around the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), an international treaty designed to harmonise IP enforcement across a number of countries, including Australia, Canada, Japan and the US. The European Union’s decision to sign the treaty in 2012 sparked protests in a number of member states and after the EU’s Parliament voted to reject ACTA, it was, at least in Europe, effectively killed off. It remains ratified by just one country, Japan.

In a speech at a conference in Berlin in May 2012 Neelie Kroes, vice president of the European Commission and digital agenda commissioner, reflected on the opposition to the proposed legislation: ‘We have recently seen how many thousands of people are willing to protest against rules which they see as constraining the openness and innovation of the internet,’ she said. ‘This is a strong new political voice. And as a force for openness, I welcome it, even if I do not always agree with everything it says on every subject. Now we need to find solutions to make the internet a place of freedom, openness, and innovation fit for all citizens, not just for the techno avant-garde.’

Reshaping copyright law has not proved any easier in the UK. The Digital Economy Act was signed into law shortly before the 2010 general election, giving authorities the power to cut off the internet connections of persistent infringers and forcing ISPs to pursue online users who regularly infringe copyright laws. Its full introduction however has been delayed first by a judicial review, then by a legal challenge by BT and TalkTalk and more recently by debate around how its toughest recommendations should be implemented.

A 2011 paper from the London School of Economics’ Media Policy Project was highly critical of the Act and reflected the challenges facing those who are keen to pass legislation. ‘The Digital Economy Act has given too much consideration to the interests of copyright holders, while ignoring other stakeholders, such as users, ISPs and new players in the creative industry,’ it said.

To those who represent traditional rights holders, however, the online world shouldn’t be given special treatment in the debates over copyright. ‘Anyone who thinks that the internet is the wild west is either a cowboy or a pirate,’ insists Kiaron Whitehead, general counsel of UK music body British Recorded Music Industry (BPI). ‘The same fundamental principle of law exists in the online world equally as much as in the physical world – namely that taking something without consent is wrong.’

Scripting a suitable ending to satisfy the interests of all of the stakeholders in this argument has so far eluded even the most creative minds.

On the rise

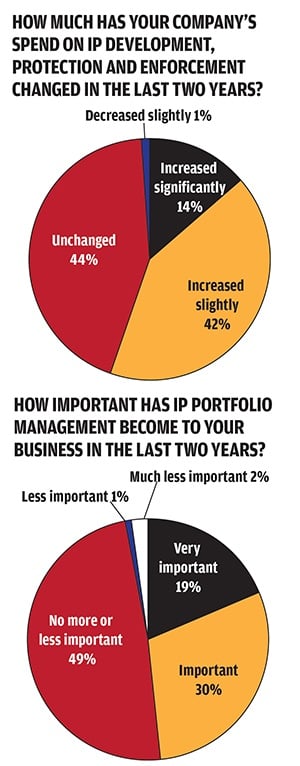

The increasing role played by IP in contributing to a company’s overall financial health was reflected in the answers to a question on how much respondents had seen their company’s spend on IP development, protection and enforcement change in the last two years. Just over half, or 56%, said that they had seen an increase, with 14% replying that spend had increased significantly.

The response undoubtedly reflects IP’s status as a counter-cyclical practice that has remained busy throughout the tough economic climate but also points to a greater awareness of IP rights. As one respondent comments: ‘Increased awareness of IP has led to increased litigation.’

‘Historically there has always been a counter-cyclical element to IP enforcement as people look to new revenue streams or perhaps move into new markets,’ says Jelf. ‘That’s always there but I don’t think it’s just that, this is part of companies refocusing their attention on IP and non-tangible assets.’

The overall theme from the survey’s results of the increased emphasis that companies are placing on IP protection and enforcement doesn’t shock one general counsel (GC). ‘It doesn’t surprise me at all,’ confirms Kiaron Whitehead, GC of BPI (British Recorded Music Industry). ‘The UK has moved from being a manufacturing-led economy to being a service-led economy, with a very talented creative and scientific sector. An increase in IP-focused investment – and the protection of that investment – is a natural consequence. The creative industries employ 1.5 million people in the UK and are worth 3% of UK gross value added. But real growth is only sustainable if active steps are taken by all of us to reduce IP infringement.’

On the soft IP side, the increase in spend may also reflect companies’ efforts to position themselves as global brands, focused not just on more mature markets but also emerging ones. Registering and enforcing trade marks therefore becomes about more than just a handful of jurisdictions in Europe and North America. ‘Now, as much as possible, brands want to be seen as global, which requires a wider trade mark search and means that they do their due diligence earlier to help prevent an expensive case later,’ says Paul Jordan, a Bristows partner specialising in brand protection.

FIGHT FOR YOUR RIGHTS – KEY RECENT IP CASES

NEWSPAPER LICENSING AGENCY V PUBLIC RELATIONS CONSULTANTS ASSOCIATION

This case is ongoing after the UK’s Supreme Court referred it to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). It revolves around the copy of an internet page that is automatically stored in a computer’s cache as part of the technological process of viewing that page and whether it is an infringement of copyright. In its judgment, the Supreme Court pointed out that the case raises an ‘important question about the application of copyright law to the technical processes involved in viewing copyright material on the internet’.

The case was brought by the Newspaper Licensing Agency (NLA), an organisation set up by a group of national newspapers to enable companies to reproduce content with permission, against the Public Relations Consultants Association (PRCA). The case focused on the services provided to the PRCA by Meltwater, a company that monitors news coverage and compiles links to stories relevant to certain key words that its customers, such as PR agencies, have chosen. The customers are then e-mailed a report, including a list of the stories with the headlines – which they can click on to see the story in full – and the opening few words. They can also access the report through the company’s website. The NLA brought the case for copyright infringement and it has boiled down to whether Meltwater’s customers need a copyright licence from the NLA.

As the Supreme Court’s Lord Sumption stated in the judgment issued in April: ‘Making mere viewing, rather than downloading or printing, the material an infringement could make infringers of millions of ordinary internet users across the EU.’

Lawyers for the NLA: Berwin Leighton Paisner – Robert Howe QC (Blackstone Chambers), Edmund Cullen QC (Maitland Chambers)

Lawyers for the PRCA: Baker & McKenzie – Henry Carr QC (11 South Square), Andrew Lykiardopoulos (8 New Square)

INTERFLORA V MARKS & SPENCER

This five-year, ongoing court battle focused on Marks & Spencer (M&S)’s purchase of a number of keywords on Google’s AdWords service. A person searching online for ‘Interflora’ and other variants would see an advert for M&S’s flower service above the natural search results. Interflora brought a case claiming that this was an infringement of its trade mark.

The case was referred to the CJEU to determine whether M&S could purchase the keywords even if it did not refer to Interflora in its online ads. In its ruling, the European court asserted that the ad has to enable ‘a reasonably well-informed and observant internet user to easily discern whether the advertisement belonged to the trade mark owner or the advertiser’.

In the UK High Court, Mr Justice Arnold ruled that it was not possible for the informed browser to determine from M&S’s adverts whether the flower service originated from Interflora or another unconnected business.

Given that this case came to focus on the internet savvy of a well-informed user, it might be expected to be challenged as people become even more familiar with Google search protocol. So while the judgment will continue to resonate in the rapidly expanding online ad market, as Bristows partner Paul Jordan points out: ‘Trade mark owners shouldn’t get too excited by the decision.’

Lawyers for Interflora: Pinsent Masons – Michael Silverleaf QC (11 South Square)

Lawyers for M&S: Osborne Clarke – Geoffrey Hobbs QC (One Essex Court)

As companies have committed more resources to IP development, protection and enforcement, it is not surprising that a significant proportion of respondents to the survey also said that the management of their company’s IP portfolio has become more important over the last two years. Just under half replied that it had become more important, with 19% of that total saying that it was a lot more important. ‘Developments in the law mean that more IP is being protected, such as databases, and businesses are beginning to try and protect property they had not before,’ comments one respondent.

‘There’s definitely more resource, attention and effort internally but that does not necessarily lead to an increase in headcount of a company’s IP team,’ says Laura Anderson, a non-contentious IP partner at Bristows. Instead clients are making better use of existing staff and senior in-housers are getting savvier. ‘There’s a greater understanding in the minds of a lot of GCs that they need to pay more attention to IP,’ she adds.

‘The demand to commercialise and enforce BT’s IP has been a constant over the last few years,’ says Rebecca Scott, GC of BT Wholesale. ‘However, we have seen an increase in the number of assertions by other companies and sectors, resulting in an increase in the need to defend. Due to the pressures to reduce cost in the business, we have not increased IP resources in-house. Instead we have adopted innovative ways of working both internally and with outside law firms to deal with the extra workload.’

Furthermore, with a better use of technology and developing systems, in-house counsel can keep tabs on their IP assets more easily. ‘GCs increasingly want a better feel on what their trade mark portfolio looks like and with the systems that now exist you can see filings for marks around the world at a keystroke,’ Jordan points out.

This climate has also led to companies reacting to more threats. Of our survey respondents, 36% said that over the last two years they had needed to protect their IP rights either frequently or much more frequently.

Another related factor in companies increasing IP spend is the growing pressure to monetise their IP assets. Forty per cent of those who responded said that it had become more important to their business to make money out of its IP in the last two years. Entering into a licensing agreement (selected by 63%) was by far the most popular method that respondents had used to commercialise their IP, followed by acquisition (26%), while 19% have used litigation as a technique for extracting commercial value from IP assets.

‘Companies don’t want to dispose of assets, so entering into a collaboration under a licence agreement provides a good way of monetising an asset,’ reflects Anderson. She points to the life sciences sector as one where developers no longer want to hand over their ideas to a large pharmaceutical company but want a continued role in product development.

This trend towards greater commercialisation has also become more apparent as some companies have shifted their business model to place greater emphasis on taking advantage of their IP rights. For instance, having sold its Devices & Services business to Microsoft for $7bn in September, including a ten-year patent licensing agreement, Nokia said that it would now focus, in part, on its Advanced Technologies business to build its patent portfolio and expand its licensing program.

For the last six years the Finnish tech giant has also been actively divesting parts of its patents portfolio as it has looked to monetise its IP. ‘We have been generating more IP than our own licensing capability has been able to monetise and so since 2007 we have entered into a number of agreements with companies that are better positioned to license and market certain technologies,’ says Paul Melin, vice president and chief IP officer at Nokia. ‘A liquid market for IP is a good thing for the technology sector.’

The increased use of licensing is not restricted to patents though, with companies looking to license their brands across multiple media channels and technological platforms. ‘You now have to get very precise in your drafting so that, say, you may specify that certain content or branding can be used in a smartphone app but then you enter into another agreement for a different format,’ Jordan says.

KEY CASES (CONTINUED)

ZTE V HUAWEI

With the ongoing disputes between Apple and Samsung over various patents in their smartphone technology, there are few sectors where the IP stakes are as high as in telecoms.

In this instance, Huawei brought a patent infringement case in Düsseldorf against ZTE over 4G phone technology. In April, the court referred a number of key questions to the CJEU over whether Germany’s approach to granting relief for infringed standard essential patents is correct. ZTE was willing to negotiate with Huawei over the use of the patented technology on fair reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms. The German approach, which is generally seen as pro-patentee, dictates that a defendant must act as if they were a licensee which, crucially, means not challenging the validity of a patent, if the licensee (in this case Huawei) is to be bound by a FRAND licensing obligation. ‘As most defendants will not [give up their right to challenge a patent’s validity] the constraint on the court to giving relief to a successful patentee in Germany is pretty limited,’ points out Bristows IP partner Myles Jelf.

Given that the European Commission, in a number of recent cases, including Samsung’s litigation against Apple, has taken the position that even asking for an injunction on a standard essential patent is an abuse of a dominant position, Germany’s stance is seen as out of kilter with many other jurisdictions.

‘What the CJEU comes back with may – if sufficiently clear – determine whether or not standard based telecoms patents are either very valuable or practically worthless,’ comments Jelf. ‘Given the size of the telecoms sector, the decision is, therefore, literally worth billions of euros.’

Lawyers for ZTE: Hogan Lovells

Lawyers for Huawei: Bird & Bird

VIRGIN V ZODIAC

The details of this case were fairly straightforward but the Supreme Court’s ruling is of potentially huge significance for patent litigation in the UK. In 2007 Virgin brought a successful case against Zodiac (then know as Contour Aerospace) in the English High Court claiming that the latter had infringed Virgin’s patent for a reclining aeroplane seat that turns into a flat bed. However, the European Patent Office (EPO) amended the patent in question meaning that, effectively, the patent that Zodiac was judged to have infringed never existed. Despite the EPO’s effective revocation of the patent, the Court of Appeal ruled that Zodiac still had to pay damages to Virgin, a ruling which was then overturned by the Supreme Court in July.

‘The Supreme Court has fairly pointedly told the Court of Appeal to look again at its guidelines on stays,’ comments Jelf. ‘When the Court of Appeal next does so, if its review of the factors relevant to deciding stay applications leads to a permissive regime, then the amount of patent litigation in the UK will drop dramatically – especially as other jurisdictions, notably Germany, do not typically stay national infringement actions pending the resolution of an EPO opposition.’

Lawyers for Zodiac: Wragge & Co – Henry Carr QC, Iain Purvis QC, Brian Nicholson (all 11 South Square)

Lawyers for Virgin: DLA Piper – Jonathan Crow QC (4 Stone Buildings), Richard Meade QC (8 New Square), Henry Ward (8 New Square)

RIHANNA V ARCADIA GROUP

Although this case may have resulted in a win for the music icon Rihanna, it was not one that could be toasted by the celebrity world as whole. Rihanna brought the case after Topshop (whose parent company is the Arcadia Group) brought out a t-shirt with a photo of her on it. The high street retailer had the permission of the photographer to use the shot but not the pop star’s.

The court ruled in Rihanna’s favour but made clear that there is, ‘no such thing as a free-standing general right by a famous person (or anyone else) to control the reproduction of their image’.

‘The court was quite easily convinced that a substantial portion of Topshop’s customers would have mistakenly thought that the Topshop garment was authorised by Rihanna,’ comments Bristows partner Paul Jordan. ‘As a result, her goodwill was damaged, both by a loss of sales to her merchandising business, and a loss of control over her reputation.’

Lawyers for Rihanna: Reed Smith – Martin Howe QC (8 New Square), Andrew Norris (Hogarth Chambers)

Lawyers for Arcadia Group: Mishcon de Reya – Geoffrey Hobbs QC (One Essex Court), Hugo Cuddigan (11 South Square)

New markets

While the opportunities in emerging markets are well known, so are the risks associated with IP enforcement. When asked to pick from a list of IP issues that have the greatest impact on their business, a third of those surveyed noted IP standards/counterfeiting in China as a problem. As one respondent comments on the most significant developments in IP law and practice over the last two years: ‘Third parties registering names despite no evidence of use and then holding you to ransom to transfer rights, particularly in Asia.’

To Bristows’ Jordan, this reflects a lack of forward planning on the part of some companies. ‘A lot of rights holders have perhaps waited a bit too long to engage with China,’ he asserts.

Just because a brand has a significant presence in the UK and Europe that doesn’t mean it extends to the Far East. ‘A big reputation here doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll satisfy the reputational requirements in China,’ he adds.

Despite the risks, the rapid development of local firms in China means that the IP climate is improving. ‘Chinese law firms are becoming increasingly sophisticated and are taking on more of a role to facilitate enforcement,’ Anderson says. In some sectors, the development of China’s IP regime actually wins plaudits. As Paul Fehlner, the head of IP at Novartis Pharma, says, China has developed a decent patent regime in a relatively short space of time and, in the pharma sector at least, does not present the same risks as India.

Ruth Daniels, GC of outsourcing company CPA Global, says managing IP rights in China is still a major concern to all CPA’s clients, even those based in Asia. ‘At the same time, the IP market in China is rapidly evolving with strong support from the government, both in terms of encouraging growth in IP filings as well as introducing ongoing improvements to the IP system, including a planned dramatic increase in the number of patent examiners,’ she adds. ‘Chinese companies – such as telecoms leaders ZTE Corporation and Huawei Technologies – now rank among the world’s biggest patent filers, and many are increasingly involved in litigation, both at home and abroad, to protect their own IP rights. As Chinese corporations continue to expand into overseas markets, they too have an increasing demand for IP management services in order to help them protect, maintain and exploit their IP assets on an international scale.’

Other key issues that survey respondents highlighted include proposed EU trade mark reforms, with 21% saying they would have an impact; keyword/comparative advertising litigation (19%); Europe’s plans to establish a Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent (19%); and class actions and third-party funding in IP litigation (18%).

IN-HOUSE PERSPECTIVES – PAUL FEHLNER, HEAD OF IP FOR NOVARTIS PHARMA

One of the biggest challenges now facing the sector, according to Paul Fehlner, head of intellectual property for Novartis’s pharmaceutical division, is the uncertainty over patent litigation created by the increased application of competition laws in the sector by authorities in the US and EU. ‘Over time, the uncertainty will be cleared up either through litigation or through political and economic changes,’ Fehlner points out. In the meantime companies, such as the members of big pharma, need to weather it as best they can.

Fehlner, who joined Novartis five years ago from Baker Botts, heads an IP team of 135 in the company’s pharmaceutical division, half of whom are lawyers. With such a prominent in-house role at one of the world’s largest drug-makers he is, not surprisingly, closely attuned to the shifting dynamics in worldwide patent enforcement.

Of the emerging markets no other jurisdiction poses more legal challenges to the pharmaceutical industry than India. In April 2013 Novartis suffered a particularly significant defeat in the Indian Supreme Court over its patent for the drug Glivec, used in the treatment of leukaemia. The court ruled that the drug shouldn’t be given a patent because it was too similar to an earlier Novartis drug. ‘It’s very frustrating,’ Fehlner admits of the court’s decision. ‘India’s IP system is evolving but it’s clearly biased to certain outcomes.’

India, has a thriving generic drug industry to promote and, as Fehlner emphasises, you can’t make a knee-jerk reaction to adverse decisions in such an important market. ‘We have to take the long-term view and point out that countries that don’t promote innovation will fall behind because in the end innovators won’t go there,’ Fehlner says. He points out that the picture is by no means as bleak in other rapidly growing markets. ‘China is looking to transform itself into an innovation economy and the IP system they have put in place is truly remarkable given the short time they’ve done it in. Is it there yet? No, but China is on the right track.’

When it comes to European attempts to establish a Unified Patent and one over-arching patent court, the UPC, Fehlner admits he’s intrigued by the prospect but says he sees some possible risks such as in the imposition of EU-wide injunctions. For instance, a case brought in one smaller jurisdiction that may be more patentee friendly or vice versa, could have profound implications for the whole continent. However, there is one country observers can look to get some sense of how the UPC may work in practice. ‘People wonder how it might work and I point out that we already have a jurisdiction with a system like it – it’s the United States.’

Trade mark reforms are due to come into force in 2014 and are aimed at streamlining registration procedures and introducing tougher anti-counterfeiting measures. The reforms have largely been welcomed by the IP community but greater uncertainty surrounds the EU’s attempts to harmonise its patent regime. In September a group of companies, including Apple, Google and Microsoft, wrote to the European Commission to voice their concerns over the proposals for the Unified Patent Court (UPC). The letter highlighted two areas for concern. The first was the potential problem of bifurcation – where a company could seek and win a ruling that one of its patents has been infringed before there has been a ruling on whether the patent is actually valid. The second issue is the application of pan-European injunctions which could ‘enable unprincipled litigants to hold up manufacturers by making unreasonable royalty demands for even a single trivial patent on a complex product’.

The introduction of a unified court remains several years away but the joint letter reflects the concern by some of the world’s largest technology companies that a new system could be open to abuse and not benefit those it was originally intended to help. ‘The proposed system is supposed to help small and medium-sized businesses but it’s not clear that the new structure will necessarily be cheaper or more workable,’ Jelf remarks. ‘Much will depend upon how the new courts apply the rules.’

In the letter to the Commission, the companies express their concern that a new system may be particularly vulnerable to attacks from patent assertion entities (PAEs) or patent ‘trolls’, which own and aggressively enforce patent rights against alleged infringers but do not manufacture the products or supply the services to which those patents relate. Although they have emerged as a significant threat to businesses in the US – they reportedly cost US businesses $29bn in 2011 – they are yet to establish themselves as a significant presence in Europe.

With cost recovery a feature of litigation in Europe but not in the US, the patent trolls’ business model faces a significant challenge in the EU as they face the prospect of covering the other side’s costs in a failed patent case. Perhaps not surprisingly then, a little over three-quarters of survey respondents said that they were ambivalent about patent trolls, with 10% saying they present new opportunities and 14% replying that they cause a significant waste of time and money.

‘Overall we feel fairly good about the prospects for IP as a business area,’ concludes Melin. ‘Our concerns relate to confusion caused by debates around hot topic areas such as standard essential patents and patent trolls. We see risks that regulators and lawmakers could take steps to steer the IP framework in directions that would not be helpful to innovation and continued investment in IP.’

IN-HOUSE PERSPECTIVES – GEOFF BRIGHAM, WIKIMEDIA GENERAL COUNSEL

Since Brigham joined from eBay in 2011, his legal team has grown from two people to half a dozen today. ‘We do pretty much everything, including privacy, trade marks, copyright, contracts, governance and litigation,’ he says. As well as the in-house team, Brigham likes to highlight the contribution of the Wikimedia community, who write the content and keep a close eye on material that might infringe copyright. That vigilance, he points out, means that Wikipedia gets surprisingly few takedown notices. ‘We’re the fifth most popular site in the world so you might expect us to be getting thousands of notices every day but in fact we get fewer than 15 [Digital Millennium Copyright Act] take down notices a year,’ he states. ‘This illustrates the power of our community in ensuring against infringement on our sites.’

Wikimedia, therefore, does not regularly come into conflict with other content producers and rights owners but, nonetheless, it has helped to spearhead the amorphous mass of opposition to attempts to strengthen anti-piracy legislation, most notably in the US with SOPA and PIPA. The two bills were both shelved days after Wikipedia demonstrated its opposition through a blackout, with the English language site taken offline for 24 hours.

Part of the problem with the legislation, Brigham says, was the lack of visibility around the whole process. ‘It was big media trying to ramrod a piece of legislation through Congress with no transparency and based on backroom negotiations,’ he claims. That lack of clarity has not been solely an American affliction, according to Brigham, with other attempts to strengthen anti-piracy laws also happening behind closed doors. ‘SOPA is not transparent, ACTA is not transparent, the Digital Economy Act is not transparent,’ he asserts.

Asked if he could see another blackout taking place, Brigham points out that the decision is one for the Wikipedia community to take but he adds: ‘Frankly I would do whatever the community says. If lessons have not been learned from SOPA then I’m willing to teach them again. Could I imagine a time when we’d propose that we needed to consider another blackout? Yes.’

The threat has at least abated for now but Brigham clearly remains opposed to sweeping legislation that lacks precision. ‘Copyright protection was always intended to be balanced and nuanced,’ he reflects. Ensuring that that balance is maintained is one of the key tasks for his six-person team. And, of course, for Wikimedia’s thousands of rights holders.

In private

Our survey also canvassed in-house teams on data protection. With proposed new regulations in the EU expected next year aimed at harmonising and toughening laws across member states, as well as the recent revelations in the US around far more extensive surveillance by the US government than previously thought, privacy is firmly in the spotlight.

The EU’s proposed Data Protection Regulation will be adopted before European elections in May 2014. The President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso, stated its adoption was of ‘utmost importance’ in his State of the Union address in September.

The majority of respondents to the survey indicated that they were adopting a watching brief before taking any steps to comply with proposed changes in the EU. Thirty seven per cent said they were partially taking steps and monitoring developments while another 37% replied they were yet to take any measures and were waiting to see the outcome. ‘It’s a highly sensitive topic so it’s prudent to wait and see how it settles down before making any changes,’ says Jelf.

‘I am keeping the proposed regulation under close review as it passes through the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs of the European Parliament,’ says Robin Saphra, group GC at Colt. ‘In particular, I am keeping the provisions on data portability in mind as Colt sees opportunities for harmonisation and the removal of barriers and the development of a truly virtual yet fully compliant offering without geographic constraints. Alongside this, however, I have a concern around the level of the proposed standard. While I acknowledge the importance of clear rules around the protection of personal data, excessive regulation can place a heavy burden on business and reduce Europe’s competitiveness in a global market. Colt is concerned to ensure that the proposed harmonising regulation is as light touch as is consistent with good practice.’

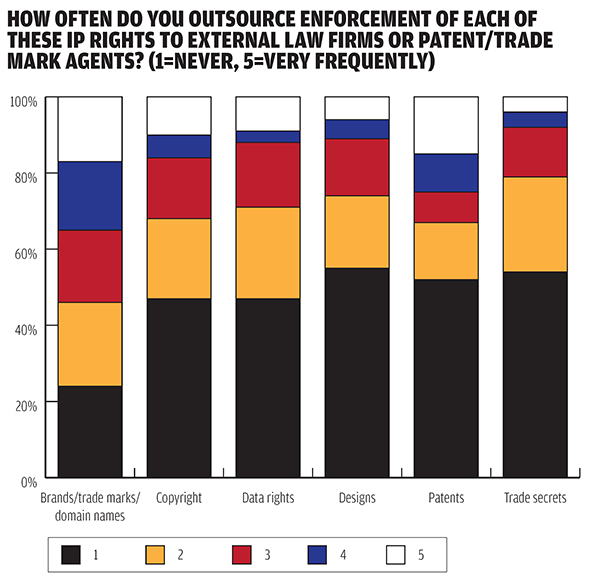

With the proposed harmonisation of data laws, trade mark regulations and a possible unified patent system across the EU, as well as ongoing attempts to strengthen anti-piracy regulations, IP policy is in the process of being transformed. With the rapid pace of technological change this transformation, in large part, makes sense. But it’s clear that IP will remain in a state of flux for years to come, assuring its position as one of the most active practice areas in most law firms. The survey results reflect this: 35% of respondents either frequently or very frequently outsource their soft IP issues externally, while 25% frequently or very frequently outsource their patent enforcement externally.

So, with businesses’ IP becoming more valuable, one familiar client gripe may remain as true as it has ever been. As one respondent comments: ‘The increasing cost of outside counsel means it is outrageously expensive to litigate, even when you believe you are in the right.’

IN-HOUSE PERSPECTIVES – KIARON WHITEHEAD, GENERAL COUNSEL, BPI

So far this year, he reveals, BPI has asked Google to remove 30 million links that infringe copyright from search results. ‘If a search engine knows that a website has been declared infringing (or has received millions of notifications regarding that illegal site), then it’s unfair to music fans searching for say “Coldplay mp3” to be served up with illegal links to Coldplay music before they see a link to a legal online service like Spotify, iTunes or Amazon. But that’s exactly what happens at the moment and the House of Commons’ Culture, Media and Sport Committee in its September 2013 report have called for action,’ Whitehead comments.

However, since he joined the BPI in 2008 from London boutique Forbes Anderson Free, Whitehead says he has seen a marked change in the attitude of the government and internet service providers (ISPs) in the fight against copyright infringement. That shift has, in part, helped bring down the level of online music piracy. In March this year, Ofcom announced that the number of songs illegally downloaded had fallen by a third year-on-year to 199 million. In another highlight, last year the High Court ruled that five leading UK ISPs should block access to The Pirate Bay, the controversial file-sharing website, a decision Whitehead describes as ‘a real turning point’.

The 2010 passage of the Digital Economy Act (DEA), which was designed to strengthen the UK’s copyright law, could also be seen as another obvious turning point but the subsequent failure to fully implement the Act’s provisions has been more than a little frustrating for the BPI. ‘It’s frustrating in the extreme that the DEA has not yet been implemented, despite it coming into force in 2010,’ says Whitehead. ‘It was challenged by judicial review up to the Court of Appeal, but the court held that the DEA is a proportionate and appropriate piece of legislation to help deal with online copyright infringement. We need it implemented.’

To Whitehead, who heads an in-house legal team of six, it’s all the more frustrating because the benefits of a rigorous IP regime to him are particularly clear. ‘You can’t have sustained, multi-faceted investment in IP in the UK without the security of a strong legislative IP infrastructure to underpin that investment.’