Once a byword for bribery, the Asia region has toughened anti-corruption measures in recent years, but enforcement remains hard to predict. We team up with Simmons & Simmons to assess the client response.

Any multinational worthy of the label has to be in east and south-east Asia. The scale of the market, its manufacturing base, and its growing consumer population make it impossible to ignore.

As a result, no other region in the world attracts more foreign direct investment (FDI). In 2013 it received $346.5bn of FDI (of which $200bn went to China and Hong Kong), compared to $246bn in the EU, $187bn in the US, $182bn to Latin America, and $103bn to Russia and the CIS. Companies have to be there and, in the early days, some would do almost anything to make that happen.

This need to establish a toehold in the region lies at the root of the problem that many companies are now facing up to. In many instances, corruption and bribery played a significant part in their initial success. However, a series of high-profile enforcement actions and multimillion-dollar fines against international companies such as Siemens, Alstom and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) has made the very largest companies recognise that the punishments for not complying with the rules can outstrip any gains made by breaking those

rules in the first place. Compliance, once perceived as a burdensome, box-ticking drag on profits, is now increasingly seen as a means by which to protect those profits.

‘It’s that age-old adage,’ says Tom Fyfe, Simmons & Simmons’ Asia head of dispute resolution. ‘If you skimp on the front end, you can often find yourself paying more.’

This level of risk management is especially important in Asia, not necessarily because it is more corrupt – there are plenty of countries in Africa, the CIS (including Russia) and Latin America that are judged to be higher risk – but because for many international companies, their exposure to the region is a huge and essential part of the business.

To get a true sense of how seriously companies are taking the issue of anti-corruption and bribery, and what measures they are taking to improve their practices in Asia, Legal Business teamed up with Simmons to survey senior executives from a range of international companies operating in the region. We also interviewed senior in-house counsel, as well as professionals at major risk management and professional services firms, all of which are working at the sharp end of the region’s most problematic jurisdictions. Of the 162 respondents to the survey, 53% ranked bribery and corruption as a major risk to the business. Among those working at companies with turnovers of more than $500m (who accounted for 55% of total respondents), this figure rose to 64%.

VAGUE AND AGGRESSIVE – FACING LOCAL REGULATORS

For those multinational companies that doubted the value of strong internal compliance procedures in their Asian operations, the first sit-up-and-take-notice moment came on 15 December 2008. Siemens, the German engineering giant, had just agreed a record settlement with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) following charges that it had violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) ‘by engaging in a systematic practice of paying bribes to foreign government officials to obtain business’. The alleged bribes that Siemens paid weren’t just limited to Asia, but violations in China and Vietnam formed a key part of the charge. The company ended up paying $1.65bn in combined sanctions to the SEC, the Department of Justice (DoJ) and the Office of the Prosecutor General in Munich. The $800m paid to the US authorities retains the dubious honour of being the highest FCPA-related enforcement to date.

The value of the fines wasn’t the only striking figure to emerge from the Siemens case. The aggregate value of the alleged bribes was also eye-watering. The SEC complaint alleged that Siemens paid approximately $1.4bn of bribes to government officials, and approximately $391m in payments to third parties, ‘which were not properly controlled and were used, at least in part, for such illicit purposes as commercial bribery and embezzlement’. The Chinese side of the Siemens story had its own harsh footnote in 2011, when Shi Wanzhong, a director of the state-run telecoms company, China Mobile, was, according to Chinese press reports, given a suspended death sentence for taking a share in over $5m worth of kickbacks for arranging a deal between the two companies. The intermediary who helped facilitate the deal and the bribes, Tian Qu, was reportedly sentenced to 15 years in prison.

The increased likelihood of prosecution from domestic regulators in China and other Asian countries adds an extra, and far less predictable, element of risk. When Xi Jinping became president of the PRC in 2012, he initiated an anti-corruption campaign that sent shockwaves through the Chinese political elite and resulted in the downfall, imprisonment and even execution of numerous high-profile Communist Party officials and senior business executives.

The corruption investigations haven’t just been limited to party apparatchiks and senior executives of Chinese state-owned enterprises. Multinational companies have also felt the full force of China’s crackdown, notably GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), the UK pharmaceutical company, which was forced to pay a record Chinese fine of close to $500m in 2014 after allegations of paying bribes to doctors and hospitals to boost sales of its medical products. The GSK case marked a significant step change from previous enforcement actions against companies like Siemens.

In the case of the Siemens scandal, any Chinese prosecutions followed findings made by the US and German-led investigations, whereas with GSK, China led the way in doling out the punishment.

‘Increasingly the Chinese regulators want to be perceived as being on the front foot,’ says a Hong Kong-based investigator at a major risk management company. ‘In my experience, the Chinese are increasingly wanting to be seen as a leader and jostling their way, particularly in their own country, to be at the front of these issues.’

The problems that multinationals faced when trying to crack Asia’s major developing economies, such as the issues of language and culture, are also present when it comes to tackling the local laws and regulators. To a large degree, the companies are dealing with an unknown quantity since the situation is evolving so rapidly. Risk is further complicated in China by the politicised nature of enforcement, with companies that have angered the state seen as likely targets. In such situations there is little practical defence.

‘In China, more attention is being given to multinationals and we have recently seen the arrest of a number of foreigners,’ says one senior in-house lawyer. ‘It is a concern that you may be dealing with local enforcement agencies who might cause more immediate problems than the US Government. The other challenge is we have years of studies on the FCPA and how it works and strong relations with the US Government. That may not be the case in local Asian jurisdictions and the local agencies are very widespread – there may be a main national level and then a provincial level – therefore it’s a lot to firm up relationships and figure out what the local regulators are interested in and what they want to do.’

‘The political and regulatory environment has changed drastically in the last 24 months,’ asserts Kent Kedl, the Shanghai-based managing director of Control Risks in greater China and North Asia. ‘The political landscape has changed, political appointees have changed. If companies are going in with an old map, they aren’t going to navigate the problem in China. One of the challenges in the past was that we used to complain about a vague law and vague enforcement of it. The law is still quite vague but the enforcement is quite aggressive, so it’s even more challenging than in the past.’

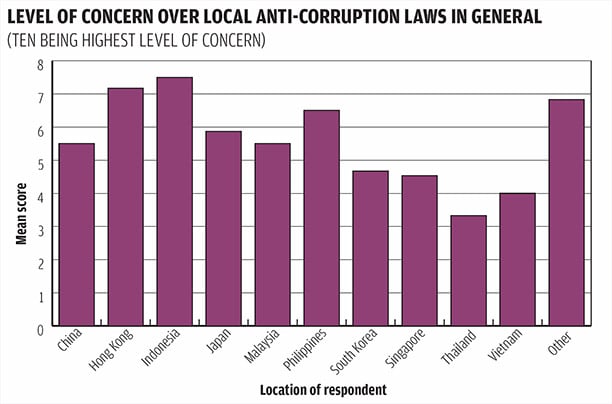

This concern is largely reflected in the survey results. When it came to the various anti-corruption laws that companies face, the local regulations present a bigger concern to those polled than the FCPA or the UK Bribery Act, which has been in force since mid 2011. On a scale of one to ten, where ten represents extreme concern, local anti-corruption laws received a mean score of 5.6, whereas the FCPA and the UK Bribery Act scored 4.57 and 4.15 respectively. One reason is the higher level of guidance and clarity from the latter two, particularly with regard to any grey areas of law. The domestic laws can be more opaque, and the regulators, especially in China, can come in many shapes and sizes. Most companies are likely to deal with the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC), but its powers can often compete and overlap with other bodies such as the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), which handles antitrust cases; the China Food and Drug Administration; the Ministry of Public Security; and the Central Committee for Discipline Inspection, which focuses on corruption within the Communist Party. Even within the SAIC, companies also need to learn how to navigate the different offices, be they on a sub-district, municipal, provincial or national level.

Root cause

‘I came out to China in 2006 when everyone was coming to Asia and particularly China, and no-one really focused on how they got in, they just wanted to be in,’ says Lesli Ligorner, a Shanghai-based partner at Simmons with a strong focus on the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) and local anti-corruption compliance. ‘Companies were being purchased, companies were being set up, employees were being brought in, and there was no real appreciation for local anti-corruption laws, against a backdrop of very little local enforcement. There was no real understanding that your local workforce in China wouldn’t understand a couple of lines about the FCPA. No-one paid attention to those issues and they compounded over time.’

This problem became particularly acute in two of the region’s largest and most targeted economies: China and Indonesia, which are respectively ranked at 100 and 107 out of 175 in Transparency International’s influential Corruption Perceptions Index – with one being excellent (Denmark) and joint 174th (Somalia and North Korea) not so good. Securing market share in these countries often requires interaction with public officials and, in the case of China, heavy reliance on doing business with state-owned enterprises (SOEs). For many companies faced with a seemingly impenetrable cultural, geographical and language barrier, there is also the risky use of intermediaries and third-party agents who have the right connections for opening up Asian markets to new entrants. To build that business, there was often a belief that facilitation payments, kickbacks and bribes came with the territory. For those western chief executives and shareholders monitoring the results from afar, the profits and opportunities helped them turn a blind eye to what was going on at ground level.

‘Foreign companies that have been here a long time haven’t necessarily done a lot of deep digging about how they got to market,’ says Kent Kedl, the Shanghai-based managing director of Control Risks in greater China and north Asia. ‘If they signed up to a relationship ten years ago, they didn’t do the due diligence and they didn’t have to at the time. They were told if there was a dodgy transaction involved, you stick a distributor in between.’ That scenario has changed dramatically.

‘In addition to the FCPA, the UK Bribery Act has made it clear that you can’t do something indirectly that you can’t do directly either,’ says Ligorner. ‘Interestingly now, China has started to focus on who is working with the intermediaries, and punishing the intermediaries and also punishing the companies that engaged those intermediaries to do their dirty work. That is new.’

While there is a growing threat from domestic laws in jurisdictions such as China, as illustrated by the recent prosecution of GSK in 2014, for most companies the biggest concern there is the vagueness of some of the laws and the capricious nature of some of the domestic agencies (see box, ‘Vague and aggressive – facing local regulators’). Largely, it is the extra-territorial laws such as the FCPA that most companies will use as a guideline. This includes Chinese companies.

‘In reality in some developing countries, even though they have very detailed anti-bribery regulations, probably the enforcement is not as strict compared to the US and UK,’ says Leslie Zhang, a division director in the project management division of the legal department of China National Offshore Oil Corporation. ‘The importance of UK, US and EU legislation will always be placed ahead because of the likelihood of enforcement.’

A relatively new entrant in this regard is the UK Bribery Act, which came into force on 1 July 2011. Like the FCPA, it can apply to a company with a relatively minor link to the UK. The legislation is fresh and relatively untested, and the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) achieved its first successful conviction under the Bribery Act in December 2014, in a case concerning bribes linked to a £23m green biofuel fraud carried out between senior executives in the company Sustainable AgroEnergy and an external agent. Nevertheless, international companies are taking the law very seriously.

‘When I have meetings with GCs here in Tokyo, they are very much aware of the risks that are connected to doing business in these new areas of the world,’ says Anthony Hague, a disputes lawyer and managing associate in Simmons’ Tokyo office. ‘Because of that, we’re seeing more of the trading companies in Japan rely quite heavily on standalone compliance desks. One comment that was made to me by a GC here in relation to the UK Bribery Act is that nobody wants to be the first company to be caught.’

Subtle differences in the competing laws do, however, lead to some confusion as to which should be applied to internal compliance procedures. In the case of the FCPA, the bribery provisions apply to foreign public officials, whereas the UK Bribery Act is stricter and also punishes the bribery of private individuals and companies. The FCPA is also more lenient when it comes to facilitation payments, such as payments that aren’t strictly speaking bribes but will help speed up bureaucratic processes, including visa applications. Such ‘grease’ payments are strictly forbidden under the Bribery Act. On the flipside, the FCPA guidance suggests much more onerous limitations on client hospitality and entertainment.

‘The guidance under the UK Bribery Act seems to permit much more lavish activity than the FCPA,’ says Ligorner. ‘Box seats at the London Olympics were probably quite expensive, and would probably be far too expensive for it to be just a nominal gift under the FCPA, whereas that had to be permitted for the Olympics, or the boxes wouldn’t be filled.’

Since most international companies are affected by both laws (as well as the relevant domestic ones), the safest approach is to follow the most onerous rules in every instance.

‘It’s important to always have regard to the highest bar, which most often is set by the UK Bribery Act,’ says Mark Jenkinson, Asia-Pacific head of legal at the Norwegian company, Petroleum Geo-Services (PGS). ‘If you are an international company like PGS with operations in the UK and US then this means your entire global operations fall within the jurisdiction of the SFO and Department of Justice (DoJ) due to the extra-territorial reach of the Bribery Act and FCPA.’

The extra-territorial nature of the FCPA, which outlaws the bribery of foreign officials for commercial gain, has been extended to foreign companies with the most tenuous of links to the US. Perhaps the most notable case in this respect was the $218m fine that the Japanese company, JGC Corporation, had to pay to the DoJ in 2011 for its part in the TSKJ joint venture, which paid bribes to Nigerian government officials to win and retain the contract for the Bonny Island LNG project. JGC wasn’t a US company or an issuer, but it fell under FCPA jurisdiction because it aided and abetted its joint venture partners, including Kellogg Brown & Root, a US company, in the payment of bribes.

CLIENT EXPERIENCES: HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGONS

Companies still dithering over whether a robust compliance infrastructure is worth the investment might want to consider the contrasting fortunes of Morgan Stanley and the cosmetics company Avon Products. In Avon’s case, in December 2014 the company agreed to pay a $135m settlement following violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). According to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Avon had failed ‘to put controls in place to detect and prevent payments and gifts to Chinese government officials from employees and consultants at a subsidiary’.

Morgan Stanley, however, faced no penalties, even though a former managing director of its Chinese real estate investment business, Garth Peterson, pleaded guilty to charges that he had acquired millions of dollars worth of real estate investments for himself and a Chinese official in exchange for business. In 2012, Peterson was jailed for nine months in the US, whereas Morgan Stanley avoided any charges. Since the SEC and Department of Justice were satisfied that Morgan Stanley’s internal procedures were robust, the bank avoided the sort of costly FCPA enforcement actions that has plagued companies like Siemens, Alstom, and now Avon.

‘This mitigates against lone-wolf syndrome – and was a victory for common sense. Up until that case there was the sense that no matter how much training you gave, if an employee decided to go off and be corrupt the organisation was still liable,’ says Mark Jenkinson, Asia-Pacific head of legal at Petroleum Geo-Services (PGS).

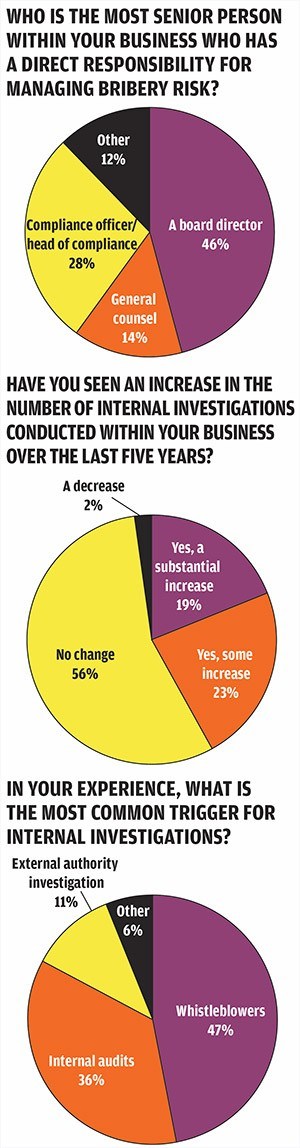

According to our survey, most companies understand this, but many still have room to improve. Only a fifth of our respondents spent more than $150,000 on anti-bribery compliance over the past three years, while only 43% reported seeing an increase in internal investigations over the past five years.

‘There has been a lot of traction on anti-corruption as lots of multinational corporations and banks have been fined,’ says Arijit Chakraborty, general counsel (GC) for Zurich Insurance in Singapore. ‘The pressure to maintain an effective anti-bribery infrastructure is big; many financial institutions now have financial crime departments with large teams.’

To make sure errors do not occur, the GCs interviewed agreed that the measures have to be exhaustive; every transaction and gift has to be transparent, signed off and logged on a register; facilitation payments should be forbidden; and management must lead by example.

‘An organisation’s anti-corruption procedures must have top-down buy-in from senior management and must be unequivocally communicated to all personnel,’ says Jenkinson. ‘An example in our industry might be where a vessel is in port waiting to get out. It is not unusual for the harbour master to prevent the vessel’s departure in the expectation of receipt of a small cash gift or box of cigarettes in return for a timely release. There used to be the sense that the captains of the vessels would have been in fear of their jobs if they didn’t make this payment. That’s really changed in recent years due to this top-down policy. This is advertised on our intranet, saying we will support you in your decision to not make such payments.’

Training day

Once a company starts exhibiting this level of intolerance of corruption from the top, the belief is that those at lower levels will have the confidence to act more ethically. Again, illustrating that the company has a strong training programme is essential, even if some rogue individuals may ultimately choose to ignore it.

‘Training is obviously very important,’ says Vanita Jegathesan, corporate counsel for Chevron in Singapore. ‘But training is only ever as good as the trainer and the topic. One of the things we found very helpful was giving employees very specific hypothetical examples. Different countries have varying risk tolerances. When you explain issues via very specific cases or examples it makes it more compelling.’

‘We have a comprehensive anti-bribery and anti-corruption framework in place,’ says Chakraborty. ‘This framework is rolled out throughout the company and we undertake frequent training with all existing employees and new joiners. Awareness of all of the issues is built into the framework and the policies. Approvals are needed for all incentives, sponsorship or any initiative where we are paying money to a third party.’

When it comes to dealing with third parties, such as intermediaries or joint venture partners, it is essential that the company can also prove that it carried out the due diligence, including regular audits if required.

‘The due diligence is the first step to control the bribery risk,’ says Leslie Zhang, a division director in the project management division of the legal department of China National Offshore Oil Corporation. ‘The legal department will conduct necessary identity due diligence on the agent. If the checks come back okay and the senior management think an agent will bring good business opportunities with manageable risks, then maybe we will enter into formal negotiations with consultants. In the agreement we ask the consultant to give their covenants that will cover two issues – that any payment the company makes under consultancy agreement will not be used for any illegal purposes and that it will not be used for any bribery actions. Our company must also have the right to audit all the expenses and how any payment made by the company is used. We ask for indemnity if these covenants are not adhered to.’

Unsurprisingly, this sort of heavy due diligence can result in conflict with commercial teams in the business who will want to get the deal done. In the larger companies with well-established and well-trained compliance teams this isn’t a problem, particularly if they have board-level backing. In the case of our survey respondents, 46% of the respondents have board directors with direct responsibility for managing bribery risk. For smaller companies, this process should often be outsourced to external advisers, who can take a more objective view.

‘If I was internal I might just give in, because I could be worn down day after day by the general manager,’ says Lesli Ligorner, a China partner at Simmons & Simmons. ‘It’s easy for me as an external counsel to say I just need a little more. There are plenty of people in China out of whom I’ve tried to tease information and they don’t like that, they don’t like me, so it’s not always the easiest job. That is the most difficult thing for very small companies. They just want to get the sale done, and someone is asking too many questions, because there is something wrong about the transaction.’

The tightening net

The tightening net

The pressure faced by in-house counsel and compliance officers is compounded by the fact that in many cases they aren’t just dealing with one country, but several, and each one will present its own challenges both in terms of the level of risk and the type of training required.

According to our survey results, Indonesia poses the greatest concern in terms of risk, followed by China as well as other emerging economies such as Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and the Philippines (see table). Indonesia proved to be a major stumbling block for the French multinational power and transport infrastructure company, Alstom, which was fined $772m by the DoJ in December 2014 for breaches of the FCPA, including paying over $75m in bribes to public officials in Indonesia, as well as Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the Bahamas.

This growing trend is likely to continue. And, as the cases and prosecutions grow in scale and profile, the public’s understanding of such matters will also increase. This awareness is increasing the likelihood of whistleblowers who, according to 43% of respondents in our survey, are the single largest trigger of internal company investigations. The growing threat of whistleblowers is unsurprising since whistleblower awards from enforcement agencies such as the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) can range from between 10% and 30% of the total penalty that a company has to pay. In September 2014, the SEC announced that it awarded a record payment of $30m to one overseas whistleblower, emphasising the international reach of its anti-corruption drive.

‘With more international co-operation between authorities there is a greater passage of intelligence and a greater ability to obtain evidence formally between jurisdictions,’ says Nick Benwell, the London-based head of Simmons’ crime, fraud and investigations group. ‘The rise in the level of enforcement, and the introduction of new laws, has led to a much greater awareness in the business world of corruption issues. In turn, this seems to be driving more whistleblower activity. That itself also feeds into a greater focus within organisations on corruption.’

This increased co-operation between authorities, the greater assertiveness from domestic regulators, combined with the extra-territorial powers of the FCPA and UK Bribery Act, has dramatically changed the risk environment in the last five years. Ultimately, the only way a company can protect itself is by increasing its defences. And the best form of defence is to comply.

SIMMONS & SIMMONS: OUR THOUGHTS

The survey reinforces what we are seeing regularly in corruption investigations and compliance work in Asia.

Globalised enforcement:

Where once the FCPA was the driving force for compliance programmes, companies are now having to factor in local laws and local enforcement. “A once-size-fits-all global compliance programme is becoming less and less feasible as more jurisdictions toughen up their anti-corruption laws and impose new requirements. Many respondents feel better informed about the impact of the FCPA or the Bribery Act than they do about local anti-corruption laws in Asian jurisdictions.” – Tom Fyfe.

Whistleblowing:

Whistleblowers are cited here as the most common cause of investigations; a global trend. “While the SEC bounty programme has attracted headlines (and adverts in China from US lawyers), other developments are equally important. Protection for whistleblowers has increased in many jurisdictions, as has awareness among employees and the number of channels through which disclosures can be made.” – K Lesli Ligorner.

The tightening net

The tightening net