If you needed confirmation of just how challenging the litigation climate is for many of the world’s banks, then JPMorgan Chase’s results for the third quarter provided it, in all their billion-dollar detail. Announcing a $400m loss for Q3 in October, the bank revealed that it had set aside $23bn for litigation costs arising from a series of regulatory investigations, resulting litigation and economic crisis-related suits.

‘We continuously evaluate our legal reserve but in this highly charged and unpredictable environment, with escalating demands and penalties from multiple government agencies, we thought it was prudent to significantly strengthen them,’ commented JPMorgan’s chief executive Jamie Dimon in a statement. By way of comparison, the bank’s litigation fund stood at $3bn in 2010.

Although JPMorgan is one of several international finance houses to face mounting legal costs its travails, in particular, reflect the challenges facing the banking sector. Today’s bank executives and senior in-house counsel face a complex web of investigations fuelling claims arising out of the financial crisis and more recent scandals, new regulatory oversight and tougher laws proposed by the likes of the Financial Services (Banking Reform) Bill in the UK and Dodd-Frank in the US.

To assess how this new environment is affecting the finance community, worked with Stephenson Harwood to canvass in-house lawyers at the major banks. We wanted to assess a range of topics, including how the volume and sources of litigation have varied in the last five years; how banks’ litigation spend has changed; their approach to bringing cases against other banks; their views on arbitration and third-party litigation funding; and their approach to selecting outside lawyers, gathering responses from more than 100 senior banking in-house counsel.

To many, both inside and outside of the banks, the shift in environment has been profound. ‘It’s changed in an unrecognisable way,’ admits one head of litigation at a leading bank. ‘It’s been driven by so many regulatory investigations and you now have so many regulatory agencies competing to issue the biggest, baddest fines.’

‘There’s been a remarkable shift in the way that people view banks in the last five or six years,’ asserts Mark Howard QC, a barrister at Brick Court Chambers. ‘Before the economic crisis, most people started from the point that banks were straightforward and honest but now the whole climate has changed. Banks’ reputations have been tarnished, not only in the eyes of the public and the press, but also in the eyes of judges.’

With cases coming to light over the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (Libor) scandal, and more expected from the brewing investigation into foreign exchange trading, those reputations are going to take some polishing.

GROWING SOME TEETH – REGULATION IN THE POST-LEHMAN WORLD

If the world’s major financial regulators could be faulted for failing to spot and prevent much of the fallout from the banking crisis, it’s fair to say that ever since the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers they have been attempting to redress the balance. The regulatory landscape that financial services firms face has never been more challenging. As Margaret Cole, the former head of enforcement at the Financial Services Authority (FSA) and now general counsel (GC) at PwC, recently told Legal Business, the regulatory framework that impacts the business in-house lawyers work in will get tougher. According to one respondent: ‘History suggests that there are more regulators now that can trace an institution’s past actions, so it’s obviously a more combative environment now than before.’

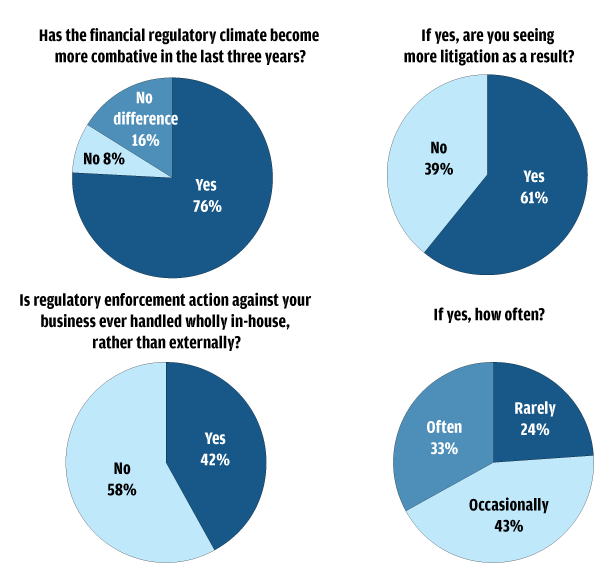

Our survey asked several questions relating to the regulatory environment that banks now operate in and the responses largely highlighted the far tougher approach from watchdogs. Just over three-quarters of respondents said that the regulatory climate had become more combative in the last three years, with 61% saying that they are seeing more litigation as a result.

Banks are quickly becoming accustomed to a new regulatory structure in both the UK and overseas, most notably in the US. Given that the successors to the UK’s FSA – the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the Prudential Regulation Authority and the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee – were only formed in April 2013, the market is still coming to terms with how the new regulatory structure will work in practice.

However, the scandal over the manipulation of Libor, a key financial market indicator based on the rate at which banks are prepared to lend to one another, has certainly given the FCA an early opportunity to prove its regulatory mettle. In October, the watchdog announced that it had fined the Dutch financial institution Rabobank £105m for Libor-related misconduct. That fine was the third largest ever issued by the FSA or FCA, and was the fifth penalty levied by UK regulators as part of the ongoing investigation (prior to its abolition the FSA announced fines against Barclays, UBS and The Royal Bank of Scotland).

In a release announcing Rabobank’s fine, Tracey McDermott, the FCA’s director of enforcement and financial crime, commented: ‘Firms should be in no doubt that the spotlight will remain on wholesale conduct and we will hold them to account if they fail to meet our standards.’

The Libor scandal has also showcased the increased co-operation between international regulators, a trend which has been evident for several years. In its investigation into Rabobank, the FCA worked closely with regulators in the Netherlands and Japan as well as the Department of Justice (DoJ) and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) in the US.

One of the features of the new tougher climate in the States has been the emergence of newly empowered regulatory bodies such as the CFTC. For a long time seen as a fairly sleepy overseer with few enforcement powers, the Commission has been reinvigorated, in part thanks to provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act that enhanced its regulatory arsenal. As a result, in the last two years the CFTC has opened a record 800 investigations and in 2012 obtained orders imposing more than $931m in sanctions.

In New York the new Department of Financial Services (DFS), formed in 2011 to improve oversight of the Empire State’s numerous financial institutions, has also hit the headlines for its regulatory zealotry. In August 2012, before federal authorities could reveal their hand, the DFS announced allegations that Standard Chartered had been involved in facilitating hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of deals for Iran, in contravention of US sanctions. The UK-based bank was ultimately fined $340m by the New York watchdog on top of a $100m fine from the Federal Reserve and a $227m penalty from the DoJ.

For regulatory investigations and litigation to arise directly out of the economic crisis, such as over the selling of poor quality mortgage securities, was not surprising. A cause for greater concern in the banking community, however, has been the number of investigations to emerge that are largely unrelated to the crisis, such as Libor and the unfolding scandal around foreign exchange rates.

‘I don’t think there’s a single reason why we’re seeing more activity, there’s simply a lot more scrutiny of the industry than before,’ comments William Sweet, head of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom’s financial institutions regulation and enforcement group. Plus there’s been a notable shift at the head of America’s flagship markets regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Since she took over as head of the SEC, Mary Jo White has indicated that she is prepared to get tougher on the financial industry than some of her predecessors. As a former Debevoise & Plimpton litigation partner and before that as US Attorney for the Southern District of New York, she might have been expected to bring a litigator’s zeal to enforcement when she picked up the reins at the SEC in April 2013. Where she has proved particularly aggressive is in questioning whether banks should routinely be allowed to neither admit nor deny wrongdoing in settling with the Wall Street regulator.

In a speech she gave in September, White suggested that in many cases a no-admit-no-deny approach was still best, but she added: ‘Sometimes more may be required for a resolution to be, and to be viewed as, a sufficient punishment and strong deterrent message.’

That change of tack is clearly resonating with the litigation Bar in the US. ‘Mary Jo White has definitely sent a message that she’s going to be more aggressive. But it will take more time for the implications of that to shake out – whether it will mean more enforcement actions, more stringent settlement demands and penalties, more trials, or different enforcement priorities,’ insists Stephen Ascher, co-chair of Jenner & Block’s securities litigation and enforcement practice. More time under a regulatory cloud like this is something that most banks would undoubtedly prefer to avoid.

On the rise

Not surprisingly, given the obvious change in climate, our survey showed an increase in contentious cases involving banks. Of the respondents, 59% said that they were involved in more litigation from 2008 to 2012 than in the previous five years. ‘The sharp increase in lawsuits as a result of the 2008 crisis makes it very apparent that litigation is almost inevitable,’ said one banking GC in response to the survey.

‘Yes, we’ve seen an increase in litigation in the financial sector,’ confirms William Luker, head of litigation at The Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS). ‘In the US, in particular, regulatory authorities and investors have shown increased appetite to pursue litigation against banks. What we haven’t necessarily seen is an uptick in banks suing one another.’

With many predicting a ‘tsunami’ of litigation after the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers, that number might have been expected to be higher. But as some point out, it’s dangerous to become too focused on statistics. ‘You have to be careful not to rely too much on numbers alone,’ warns Credit Suisse’s global head of litigation, Pierre Gentin. ‘The real story is the significance for the industry of the litigations filed after the financial crisis.’

While much of the recent focus has been on the myriad claims facing JPMorgan and in particular its November $13bn settlement with the Department of Justice (DoJ) in the US over sales of mortgage securities, it is by no means the only bank to face paying out billions.

According to data firm SNL Financial, in March the six largest US banks, including JPMorgan and Bank of America, had racked up $63bn in settlements related to the financial crisis and scandals such as Libor since 2010. With JPMorgan’s mounting costs, that total could easily pass $100bn.

Our survey showed a mixed picture when respondents were asked about the current level of claims compared with the five-year period of 2008 to 2012. A little less than a third (31%) said that they were now seeing more litigation, while 35% said they were seeing less and 34% responded that it had remained the same. The varied picture from these responses reflects the wide range of cases that different types of banks are facing.

‘The mixed results for this question perhaps reveal the experiences of different institutions,’ comments Edward Davis, a litigation partner at Stephenson Harwood. ‘Generally you would have thought that many banks are seeing less litigation now as the economy and the markets improve, but on the other hand, certain institutions will no doubt be seeing more. For example, the UK clearers who are facing payment protection insurance (PPI) and interest rate swap mis-selling claims or the larger banks facing claims arising from international regulatory investigations.’

As Gentin points out, there were cases that arose immediately following the economic crisis concerning issues like the collapse of Lehman and then, after that, there was a sense that the financial community was over the worst of the claims. What has happened since is that, as the economic climate has remained depressed, those that were waiting to see if asset values would rise are now bringing claims before the statute of limitations runs out. ‘The number of cases grew after the financial crisis but of more relevance is that these are not insignificant cases,’ Gentin says. ‘The intensity of litigation and regulatory activity that banks are currently facing is historic in nature.’

In terms of where claims are stemming from, our survey asked respondents if they were seeing more from mis-selling; more claims being brought by hedge funds; more from defective legal documentation; and more claims consequent on regulatory investigations. Most had seen more claims for mis-selling (46%) and cases stemming from regulatory investigations (49%).

As has been seen in the regulatory investigations into Libor and the controversy over PPI and interest rate swaps, there has been a steady stream of suits arising from both areas (see box, ‘Recent key banking cases from the crisis’, opposite). Claims arising from defective legal documentation were singled out by 27%, some way behind the two most common sources of claims, but it is a figure which Stephenson Harwood’s Davis points out as slightly surprising.

‘There was a line of thought at the start of the crisis that there might be more claims against law firms as transactions and their documents come under scrutiny,’ he says. ‘While there may not be more claims against law firms as such, there is plainly a feeling among many banks that poor documentation is responsible for more disputes.’

Where there hasn’t been an increase in activity is in bank-on-bank litigation. Just over 60% of respondents said that they always tried to avoid litigation with other banks and made greater efforts to settle these types of disputes. Apart from a couple of headline disputes in the last five years, such as and , there have been notably few cases. ‘There was a lot of talk about bank-on-bank litigation and a number of high-profile disputes but these results suggest that banks have always tried to avoid those type of cases and that hasn’t changed since the crisis,’ says Davis.

One respondent to the survey sums up the prevailing attitude: ‘We are not afraid to litigate against other banks whenever needed but it all depends on the issues involved and the circumstances and the cost implications. We always try to find an amicable way of dealing with the situation first but it does not mean that we avoid litigation.’

When respondents were asked where they expect more litigation to come from over the next three to five years, the spectre of greater regulatory oversight once again loomed large. On a scale of one to five, with five being strong agreement, respondents scored whether they anticipated more litigation from four specific areas. Claims consequent on regulatory investigations received the highest average score at just over 3.5. None of the other three areas – claims arising from formal insolvencies of zombie companies, limitations expiring from 2007/08 credit crunch issues and refinanced loans coming to maturity – scored above 2.8.

The unprecedented levels of regulatory scrutiny and sanction imposed on the banks (see box, ‘Growing some teeth’) has been manifest by the number of high-profile hires from the regulatory arena made by some of the biggest banking institutions. For example, Lloyds Banking Group made a significant splash when it hired the former general counsel (GC) of the Financial Services Authority (FSA), Andrew Whittaker, as its current GC in June 2012. Other high-profile hires include Stuart Levey, a former DoJ associate deputy attorney general who joined HSBC as chief legal officer in January 2012 in the wake of wholesale investigations in the US and UK over the bank’s money-laundering compliance procedures. These investigations saw the bank fined $1.9bn – then the largest ever bank payout to date – over its inadequate anti-money laundering system a year ago. Barclays also replaced outgoing GC Mark Harding this summer with Bob Hoyt, GC and chief regulatory affairs officer at PNC Financial Services and the GC at the US Department of the Treasury from 2006 to 2009, as well as a former special assistant and associate counsel at the White House.

Speaking to recently, Whittaker emphasised how crucial a constructive relationship with the regulators is to the banks, saying that although the regulatory landscape is tougher, the response shouldn’t be to push back – banks and regulators should have shared objectives so that when there’s a new regulatory initiative, the banks will work with the regulators. Meanwhile, former head of enforcement at the FSA and now GC at PwC Margaret Cole points out that regulators collectively are making a point of sending a message to financial institutions through their enforcement activity – therefore it is essential that in-house teams have individuals that are adept at understanding financial watchdogs.

RECENT KEY BANKING CASES FROM THE CRISIS

Deutsche Bank v Sebastian Holdings

This case was one of the largest ever to be heard in London’s High Court, brought by Deutsche Bank over $240m in losses incurred at the height of the financial crisis by Sebastian Holdings, the investment fund run by Norwegian businessman Alexander Vik. Sebastian then launched a counter-claim against the bank for $8bn in damages.

The case centred on a series of complex currency trades that unravelled dramatically after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, forcing Deutsche to make large margin calls to cover Sebastian’s positions. Those calls, Vik claimed, caused him to close down a number of profitable positions, hence his claim against the bank.

After a four-month trial in the High Court, Mr Justice Cooke found in favour of Deutsche, ordering Sebastian to pay $240m. At the time of going to press costs had not been awarded although, with the two sides fielding four and five counsel and the case stretching over several months, it could be one of the costliest claims to arise from the crisis.

For Deutsche Bank: Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer; David Foxton QC of Essex Court Chambers; and Sonia Tolaney QC of 3 Verulam Buildings

For Sebastian Holdings: Travers Smith; and David Railton QC of Fountain Court

Graiseley Properties v Barclays Bank; Deutsche Bank v Unitech

Although these were brought as two separate cases, they took on combined significance when a Court of Appeal judge ruled in October that parties could attach accusations of Libor rigging to their cases against the banks.

Both were originally brought as claims concerning the mis-selling of interest rate swaps which turned sour in the financial crisis. Graiseley Properties, part of the Guardian Homes Group nursing homes business, launched a claim against Barclays in April 2012 over its purchase of certain swap and collar derivative products, which were used to refinance two loans that the bank had issued.

After news of the Libor scandal broke in the summer of 2012, Graiseley added an allegation to its claim that Barclays had misrepresented the Libor rates. Among a group of banks accused of manipulating Libor, a key benchmark determined by the rate at which banks are prepared to lend to one another, Barclays was fined $450m by US and UK regulators.

In the Unitech case, Deutsche Bank sued the Indian property company over the repayment of a loan and a further $11m owed for a related interest rate swap. Unitech then counter-sued, claiming that both the loan and swap were linked to Libor rates. As in the Graiseley case, Unitech sought to amend its claim to add allegations of Libor manipulation, a move that was rejected in February 2013 by Mr Justice Cooke. However, in light of the Graiseley ruling, the Libor decisions in both cases went to the Court of Appeal where Lord Justice Longmore ruled that both claims could proceed.

The Graiseley case is scheduled for April 2014 and looks set to become a key test case for Libor-related claims.

For Graiseley: Cooke, Young & Keidan; and Stephen Auld QC of One Essex Court

For Barclays: Clifford Chance; Robin Dicker QC and Jeremy Goldring QC of South Square

For Deutsche Bank on the lenders’ action: Allen & Overy; and Richard Handyside QC of Fountain Court

For Deutsche Bank on the swaps action: Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer; Mark Hapgood QC of Brick Court; and Timothy Howe QC of Fountain Court

For Unitech: Stephenson Harwood; and John Brisby QC of 4 Stone Buildings

On the outside

Increased regulatory oversight may be part of the new dynamic for banks, but they do not appear to be seeing a change in the volume of claims from overseas jurisdictions. Just under three-quarters (72%) of respondents to our survey said there were no specific foreign jurisdictions where they were seeing more litigation. Of those that did report an increase, the US was most regularly cited (67%), followed by Europe (44%) and then Asia (22%).

To Stephenson Harwood litigation partner Sue Millar, the number who highlighted Asia was significant. ‘Now that the world economy is increasingly moving east, you have to ask whether that’s where more and more claims are now going to come from.’

Clients also point to the rise of claims and the tougher regulatory climate overseas. ‘Historically other parts of the world like EMEA and Asia have been significant in our global litigation docket but less so than the US,’ comments Gentin. ‘In recent years, there’s been an increase in litigation and regulation in Europe and Asia with more scrutiny of the industry.’

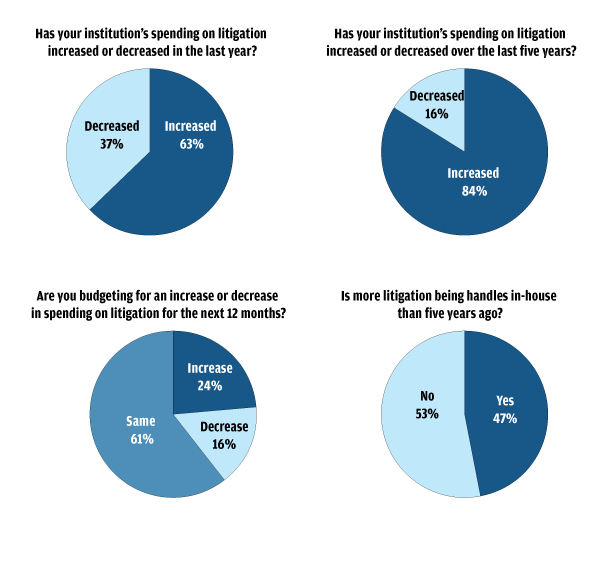

As the volume of litigation that the survey respondents have seen has increased over the last five years and the breadth and depth of regulatory action has increased markedly, it’s not surprising that litigation spending overall has been on the increase. When asked whether their institution’s spending on litigation had increased since 2008, 84% said it had gone up. In addition, just under two-thirds (63%) responded that spend had increased in the last year.

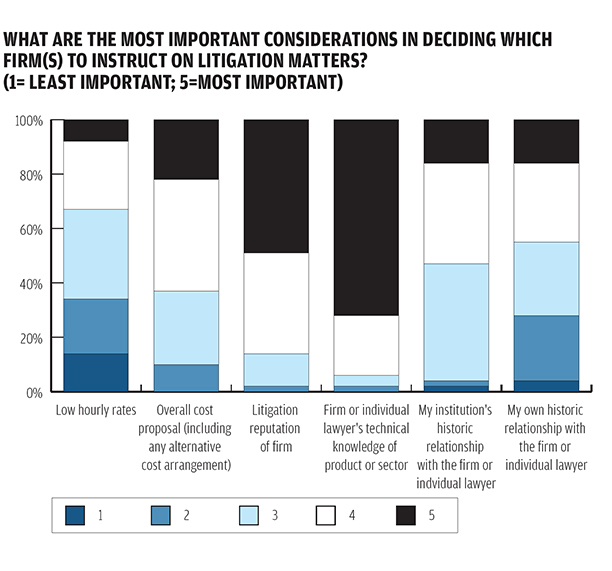

Although there has been much focus across the market on driving a better deal with external advisers, the response to our survey indicated that litigation remains less price sensitive than many other practice areas. The litigation reputation of a law firm and a firm’s or individual lawyer’s technical knowledge of a product or sector were pinpointed as by far the most important areas to consider when appointing an external adviser.

On a scale of one to five, low hourly rates emerged as the least important criteria, scoring an average of 2.94 compared with a firm’s reputation at 4.33 and a firm or lawyer’s technical knowledge at 4.65. ‘It’s interesting to see that historic relationships are important and that hourly rates and the overall costs proposal are not seen to be as important,’ Davis comments.

Of course, financial institutions are not oblivious to the cost of a case – a law firm’s overall costs proposal, including any alternative costs arrangement, was considered important, scoring 3.75 on average – and as early pioneers of panels, banks have been leaders in extracting greater value from the law firm/client relationship. But as the balance of power in that relationship has continued to shift in the last five years the focus has been about more than just a firm’s fees.

‘We’re now more demanding – all clients are – and firms recognise that,’ Luker points out. ‘We’ve grown with our panel firms and the best relationships are those where the line between internal and external lawyers breaks down.’

For Gentin, the more hostile litigation and regulatory climate has not meant that he has had to expand his in-house litigation team (he heads a group of around 45 litigators spread across the bank’s New York, London, Zurich and Hong Kong offices). Instead, he emphasises getting the balance right between two important factors.

‘We have to be very much focused on both internal and external costs,’ he remarks. ‘But we also have to ensure that we don’t compromise externally or internally on quality. It’s a nuanced exercise in terms of being attentive to who you need both internally and externally.’

Last year Gentin led an extensive review of Credit Suisse’s external litigation advisers in the US – the jurisdiction where it still sees the majority of its contentious cases – so that the bulk of the bank’s cases are handled by a smaller group of firms, a move which he says will mean that the bank’s litigation spend is less this year than it was in 2012. Although he declines to name which firms make up that smaller group, the bank has in recent years instructed the likes of Davis Polk & Wardwell, Cravath, Swaine & Moore, Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy and Cooley on litigation matters.

‘In 2013, we negotiated highly structured deals – with a small group of carefully-selected counsel – that were designed to cover most of our current and anticipated expense in 2013,’ Gentin reveals. ‘The structures include features that are more complex than is typical including give-backs, caps, tiers of discounts and tranches of free work. The point is that counsel have had to manage to targets just as we do internally. And the result has been that we’re on track for lower 2013 external litigation expenses in the US than we had in 2012.’

As well as banks like Credit Suisse taking steps to change how they use outside counsel, law firms have been eager to offer a wide variety of arrangements to satisfy banking clients. According to our survey, reduced hourly rates remains firms’ favoured approach, with 80% of respondents saying they had been offered a lower rate in the last 12 months and 70% saying they had requested one.

The next most common offer from firms was capped fees (78%) followed by blended hourly rates (59%), bulk discounts (57%), budgets for each stage of the litigation (52%) and caps for each stage of the litigation (50%). ‘There’s been a lot of talk about the death of hourly rates but there seems to be a reluctance to grapple with other ways of funding litigation and capping costs exposure,’ says Millar of the results. ‘My experience is that we’ve tended to offer conditional fee arrangements (CFAs) and with certain banks that works, there’s not really a downside to it.’

‘We have seen little take-up of alternative arrangements by banking clients – even when we have been proactive in offering these in relation to disputes on which we are instructed,’ adds Davis. ‘There is clearly demand generally for law firms to come up with alternative and more sophisticated proposals for dealing with litigation, other than just a reduction in the hourly rate, and that is perhaps not yet something that the banks have been insisting on.’

RECENT KEY BANKING CASES (CONTINUED)

Harbinger Capital Partners v Andrew Caldwell (the independent valuer of Northern Rock)

In the UK, the problems at Northern Rock were the first sign of a crisis in Britain’s banking system. When the bank was nationalised in early 2008, Northern Rock shareholders lost significant sums. The hedge fund Harbinger Capital challenged the decision of the bank’s independent valuer, Andrew Caldwell, not to award compensation to the bank’s shareholders, after he assessed the value of their shares.

In May 2013 the Court of Appeal ruled that Caldwell was right in his decision, rejecting the claimant’s assertion that its shareholding could be worth as much as £400m. Harbinger lost a first case in 2011 but opted to appeal the ruling that its shares were worthless.

It was not the first case to question the nationalisation of Northern Rock. In 2009 the hedge funds SRM Global and RAB Special Situations brought a claim against the Government but had their case thrown out.

For Harbinger: Brown Rudnick; Mark Phillips QC of South Square; and Monica Carss-Frisk QC of Blackstone Chambers

For Andrew Caldwell: Mayer Brown; and Mark Howard QC of Brick Court

John Green and Paul Rowley v RBS

This was one of the first cases brought over the alleged mis-selling of interest rate swaps. Property developers Green and Rowley funded their real estate business, in part, with financing from The Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS). In 2005 they entered into a £1.5m base rate swap agreement where if the base rate exceeded 4.83%, the bank paid the pair the difference between the base rate (4.75% at the time of the swap) and 4.83%, but if it fell below 4.83% they would have to make payments to the bank. The deal proved beneficial as rates remained high but was hit by the economic crisis and the collapse of interest rates in 2008. When Green and Rowley enquired about ending the swap early in 2009, they were told it could cost almost £140,000.

In their claim, the businessmen alleged that RBS had given negligent advice and that if it hadn’t been for the bank’s breach of duty they would never have entered into the swap.

Proceedings began in May 2011 before reaching the Court of Appeal in October 2013 with the claims for negligent mis-statement and breach of duty to give suitable advice dismissed. Crucially Green and Rowley had no notes or other documents detailing a 2005 meeting with the bank to put the swap in place, while RBS had its own account of the meeting.

In the original judgment, Judge Waksman QC emphasised that it was a highly fact-sensitive case and therefore it has been viewed as precedent setting for the slew of other interest rate swap mis-selling claims to arise since the crisis.

For Green and Rowley: Clarke Willmott; David Berkley QC of St Johns Buildings

For RBS: Dentons; Andrew Mitchell QC of Fountain Court

Zaki v Credit Suisse

This 2011 case was one of many to arise over the alleged mis-selling of complex financial products before the financial crisis, which quickly turned sour after the collapse of Lehman. The claim was brought by the widow of Mohamed Magdy Zeid, an Egyptian businessman who, between 2003 and September 2008, bought 39 structured products from Credit Suisse’s UK operations. The claim focused specifically on ten notes, all of which were leveraged, that Zeid purchased between early 2007 and June 2008. In October 2008 Credit Suisse issued a margin call and when Zeid did not transfer the required additional collateral, the bank liquidated the notes causing Zeid to suffer a loss of almost $70m.

After Zeid died in 2010, the claim against Credit Suisse was brought by his widow, Soheir Ahmed Zaki. It boiled down to whether Credit Suisse had made a personal recommendation to buy the notes and, if that were the case, whether the bank had taken reasonable steps to ensure that its advice was suitable for Zeid. After the first case ruled in favour of the bank the claim made its way to the Court of Appeal, which upheld the earlier decision.

For Zaki: Howard Kennedy; Robert Anderson QC of Blackstone

For Credit Suisse: Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer; Adrian Beltrami QC of 3 Verulam Buildings

Finding an alternative

Banks obviously don’t lack options when looking to lower their litigation bills but the results from our survey would suggest that they are not embracing some of the newer, more innovative funding techniques. Third-party-litigation funding, a financing mechanism that has only begun to get significant traction in the last five years, remains largely unpopular with major financial institutions.

Just 13% of those who responded to our survey said that they had entered into a third-party litigation funding and/or an after-the-event (ATE) arrangement in the last five years. Asked if they would consider such an arrangement in the future, 54% replied never, with 29% saying they would only consider it in extreme or rare circumstances.

Firms are clearly aware that banks are reluctant to consider third-party funding or ATE – in our survey only 15% had been offered third-party funding, while 11% had been offered ATE. Given that third-party funding is typically used on the claimant side and banks often find themselves as the defendant in a case, the uptake might be expected to be low.

On the flip side, banks are finding themselves increasingly dragged into more appearances in court because of litigation funding as would-be claimants can rely on the deeper pockets of hedge funds and other alternative investors to take the banks all the way in a dispute (see ‘How to win cases and influence people’). A recent example is Harbour Litigation Funding bankrolling a claim against Barclays, alleging the bank misused confidential information in its 2010 takeover of Tricorona. The £164m claim has been brought by UK trading and investments firm CF Partners, which alleges that Barclays used confidential information it supplied to the bank when requesting funding for its own bid for Tricorona.

But third-party funding also poses wider challenges to banks. ‘It’s not something we would ordinarily use,’ says RBS’s Luker. ‘We want to retain full control over any litigation that we’re involved in. There are collateral reputational issues that are very important to us.’

The question is whether this attitude will soften as third-party funding and ATE become more widespread. ‘Banks’ attitude to third-party funding potentially could change, I don’t see why it wouldn’t,’ suggests Millar. ‘It’s surprising that things like buying ATE to cap exposure hasn’t attracted more interest as a cost management tool.’

While financial institutions have been slow to catch on to new methods for funding litigation, our survey reveals that they also remain less than convinced on the merits of arbitration. A little over a third (35%) said that they were considering using arbitration more often than five years ago. The same percentage responded that their institution tends to avoid arbitration, with price/value (56%) and perceived lack of speed (44%) the leading reasons for avoiding it.

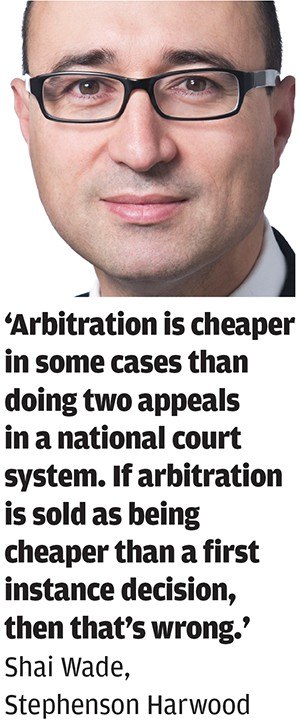

‘Arbitration is cheaper in some cases than doing two appeals in a national court system,’ comments Stephenson Harwood arbitration partner Shai Wade. ‘If arbitration is sold as being cheaper than a first instance decision, then that’s wrong.’

‘The results suggest that there are still concerns about things like quality of arbitrators and price and there are perhaps other issues like non-enforceability in many jurisdictions of hybrid or one-way clauses, which banks have used quite widely,’ comments Davis on banks’ reluctance to arbitrate.

Although the results from our survey suggest that litigation remains the favoured form of dispute resolution for banks – or perhaps the least worst option – arbitration’s appeal may grow as financial institutions grow their business in emerging markets where the local court system may not be the preferred venue to settle disputes. In addition, the creation of the Panel of Recognised International Market Experts in Finance (or PRIME Finance), a specialist arbitration centre for the settlement of complex financial disputes established in 2012 by Lord Woolf and former Allen & Overy partner Jeffrey Golden, reflects a growing acceptance that traditional litigation doesn’t always offer the best method of settling banking disputes.

And even if arbitration isn’t the best option, banks are prepared to consider some form of alternative dispute resolution. ‘We’ve always been supporters of ADR,’ insists Luker. ‘It’s hard to argue against it if there’s a means of satisfactorily settling a dispute without the cost and time of going to court.’

Gentin also underlines the benefits of using mediation. ‘It’s a flexible way for in-house counsel to discuss potential resolution in a neutral format,’ he says. ‘We have found mediation a good tool to send signals in cases, gain information and explore settlement.’

Although the survey points to an increase in litigation and a clear rise in litigation spending, the last five years have not seen banks shift their attitudes on ADR or more sophisticated forms of billing. The irony is, of course, that banks remain arguably the most sophisticated users of legal services as they have pioneered the use of panels and led the way on leveraging their buying power with external advisers.

As Stephenson Harwood’s Millar emphasises, banks may have their budgeted legal spend but what they value over everything is certainty and, ‘there may be no signs that greater flexibility will reduce costs and bring more certainty.’

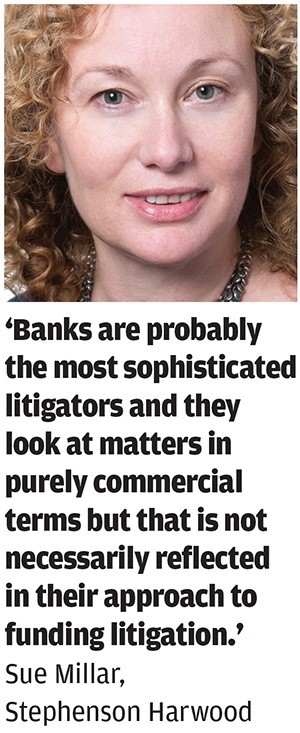

‘Banks are probably the most sophisticated litigators and they look at matters in purely commercial terms but that is not necessarily reflected in their approach to funding litigation,’ she adds.

With banks’ litigation coffers continuing to swell as regulatory investigations and claims mount, the need to view disputes in purely commercial terms has never been more pressing.