It turns out that the next risk front facing business and promising to reshape the role of general counsel (GCs) is a piece of legislation notorious among lawyers for having no teeth and little direct liability for companies.

The Modern Slavery Act came into force in the UK on 26 March 2015, consolidating existing legislation on slavery and forced labour. Yet beyond requiring companies to declare policies on stamping out slavery and human trafficking – and companies are allowed to say they have no policies – the legislation does not impose any direct legal liabilities on corporates.

Despite this, the Act is viewed by many GCs and advisers tracking the area as symptomatic of how human rights have over the last 15 years become mainstream business considerations, increasingly blurring potentially devastating reputational risks with traditional legal liabilities.

If the decades-long march towards tougher regulation, most evident in the crackdown on bribery and corruption, has transformed the role of company legal teams, human rights issues are to some lawyers the next stage of that evolution, pushing GCs into a wider range of matters well beyond traditional legal and regulatory considerations.

The Modern Slavery Act – which is expected to catch around 17,000 businesses – is a reflection of the global expansion of human rights-related legislation targeted at corporations and adopted in the wake of the 2011 endorsement of the UN Guiding Principles (see box, ‘The UNGPs’, below). PepsiCo’s GC and vice president of policy and government affairs, Tony West, says the impact of these developments on large businesses has accelerated the trend for the in-house legal function to subsume more non-legal responsibilities. ‘There’s no question the role of the GC has changed dramatically in the last ten years in a lot of Fortune 500 companies. GCs find themselves counselling not just what is legal but what is right and those are increasingly seen as two different things by wider society.’

Felix Ehrat, group GC of Novartis, agrees: ‘We are moving toward a world in which there is less focus on direct legal accountability and responsibility and more focus on not damaging the reputation of the business.’

As pressure on organisations to demonstrate human rights standards grows, the way in-house lawyers advise their organisations is undergoing a profound change. As Stéphane Brabant, co-head of Herbert Smith Freehills’ (HSF’s) business and human rights group, puts it: ‘The job of the lawyer is not only to advise on the content of the law, but to serve as a strategic adviser that anticipates issues. Human rights are not a law-free zone for businesses. Failing to respect human rights presents real legal risks for companies and the way lawyers, both in-house and external, advise businesses requires a new way of thinking – this is a new legal practice.’

To address this rapidly emerging legal field, we teamed up with HSF for an Insight focused on the latest in-house and academic approaches to human rights in business, drawing on the views of a string of senior specialists in the area, as well as 275 senior in-house counsel responses to our survey.

As pressure on organisations to demonstrate human rights standards grows, the way in-house lawyers advise their organisations is undergoing a profound change. As Stéphane Brabant, co-head of Herbert Smith Freehills’ (HSF’s) business and human rights group, puts it: ‘The job of the lawyer is not only to advise on the content of the law, but to serve as a strategic adviser that anticipates issues. Human rights are not a law-free zone for businesses. Failing to respect human rights presents real legal risks for companies and the way lawyers, both in-house and external, advise businesses requires a new way of thinking – this is a new legal practice.’

To address this rapidly emerging legal field, we teamed up with HSF for an Insight focused on the latest in-house and academic approaches to human rights in business, drawing on the views of a string of senior specialists in the area, as well as 275 senior in-house counsel responses to our survey.

Blurred lines

While non-binding frameworks such as the UNGPs are accelerating the trend toward quasi-legal accountability, they have also led to the introduction of a number of legal statutes, one of the most prominent of which to date has been the aforementioned 2015 UK Act. The Act has no power to compel disclosure (short of putatively obtaining a court order forcing companies to release a statement) and sets no formal requirements as to what a compliance statement should look like. Nonetheless, argues HSF partner Daniel Hudson, this, like many mandatory reporting laws, creates a set of risks well beyond the legislative force of the Act itself.

The legislation has been given fresh support in government by the elevation in July of former Home Secretary Theresa May to prime minister. May, who had overseen the law’s passing at the Home Office, announced the creation of a new UK cabinet taskforce on modern slavery on 31 July, also allocating £33m from the aid budget to back initiatives overseas. The Home Office estimates there are 10,000 to 13,000 victims of modern slavery in the UK, against a projected 45 million globally.

Says Hudson: ‘The Modern Slavery Act has almost no prescriptions beyond prohibiting certain conduct and offences, but once you require companies to issue a statement they are inevitably going to want to say they are doing everything in the proper manner. If companies don’t live up to their own statements there is a potential for litigation and enforcement. That means the legal team need to keep a close eye on what is being said.’

The theory is that by publicly stating its operations abide by a set of standards a company can create a duty of care and expectations from external stakeholders and introduce legal exposure to claimants in instances where human rights standards are not met (in the expanding corporate argot of human rights, such exaggerated claims are dubbed ‘bluewashing’).

There have been lawsuits brought against companies for not adhering to their own non-financial disclosure statements, typically resulting from problems encountered in remote parts of the supply chain, though the evidence for widespread litigation risk remains weak.

However, as Nestlé chief legal officer Ricardo Cortés-Monroy argues, human rights statements are creating new legal liabilities to consider: ‘Many companies now have corporate business principles or a code of ethics incorporated in reference to things like the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guidelines. GCs need to ask what we are creating by doing this. While there haven’t been too many cases in court, it is clear that plaintiff attorneys are trying to create liability by using statutory law in a given state and showing inconsistencies with a voluntary commitment to human rights.’

Stéphane Brabant,

Herbert Smith Freehills

Sanctions or financial penalties imposed by the courts are not the only risks businesses face. Liabilities in relation to other stakeholders (financers, shareholders, customers) and the risk of reputational damage is increasingly deemed at least as significant a concern. Brabant describes these as the ‘new judges’, with the potential to impose hard sanctions through soft law instruments, adding: ‘No project will be considered bankable by major lenders if it doesn’t meet basic human rights standards.’

As Hudson puts it: ‘Businesses need to realise that even if there isn’t a piece of law that says: “You must do this!” customers, shareholders, NGOs and lenders will expect them to perform to high standards and there will be drastic consequences if they don’t. The way I approach it with corporate clients is to say don’t worry simply or unduly about criminal/litigation risk. Worry about the reputational risk if you’re caught out. That is often a potentially bigger financial risk anyway.’

Brian Lowry, deputy GC at Monsanto, strikes a similar note: ‘Ultimately there may be no violation found for which you are accountable, but what difference does that make after you’ve been vilified and identified as benefiting from human rights abuses?’

This, says Jonathan Drimmer, vice-president and deputy GC at Barrick Gold Corporation, introduces a series of complicated questions which can be boiled down to a simple formula: ‘A lot of the assumptions about how non-binding standards might introduce new risks have yet to be fully tested in court, but on a fundamental level a company shouldn’t be promising something if it’s not doing it. We live in an era where transparency is expected and, if an organisation is doing something, it should be happy talking about it. It’s about not overpromising or overstating.’

Not overstating, however, is far from a simple issue, legally speaking: ‘The biggest human rights challenge for lawyers,’ says Maarten Scholten, senior vice president and GC at Total, ‘is that once you issue policies you have to make sure the published statements match the on-the-ground reality. That takes an awful lot of fact-checking, legal analysis and drafting. You can no longer sit in an office and read legal texts to do this type of compliance; you or your team have to be in the field.’

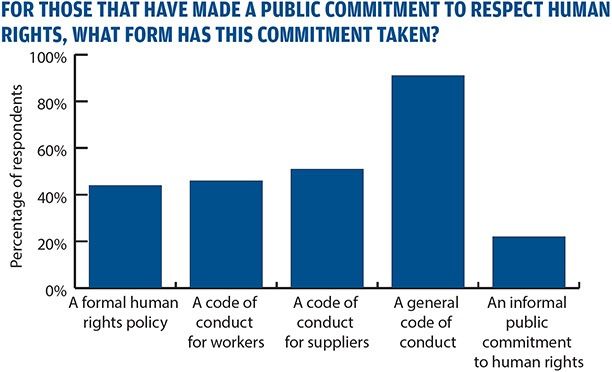

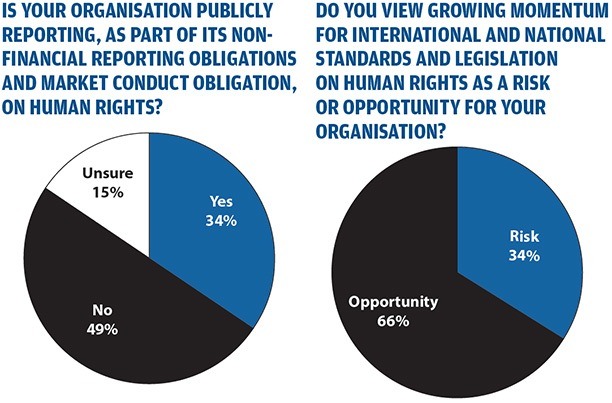

Anyone doubting the rapid spread of such issues for GCs only has to glance at some headline findings of our survey, drawn from the responses of 275 senior in-house counsel across a range of industry sectors. Nearly half of respondents’ organisations (46%) have made public commitments to respecting human rights. Where such human rights commitments have been made they most commonly refer to either national laws or the UN guiding principles.

Given the avalanche of publicity that greeted the Bribery Act, it is striking how little attention has been paid to an issue that is already demonstrably reshaping business practice.

Fifty-one percent of in-house counsel report changes to their supply chain management to support human rights, while 46% have already encountered human rights clauses in commercial contracts. Legal teams are currently the most commonly assigned to take overall responsibility for human rights issues, cited by 29%, against 27% for compliance and 19% for corporate social responsibility (CSR) teams.

In the field

The increased focus on ethical issues within the supply chain has been one of the major developments in business and human rights over the past few years. This has been particularly important for in-house counsel. ‘Supply chains are now the fundamental point of intersection between the GC and the business,’ says Cortes-Monroy. ‘On the day-to-day level supply chain management is how these wider issues translate into legal work.’

Justine Nolan, associate professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of New South Wales and deputy director of the Australian Human Rights Centre, argues that the growing attention paid to supply chains is a sign that business and human rights is maturing as a field: ‘It’s very easy for companies to have a superficial conversation about principles, but when you get into how you manage the supply chain on a daily basis, that’s a much more nuanced debate.’

Daniel Hudson, Herbert Smith Freehills

‘The biggest human rights challenge for lawyers is you have to make sure the published statements match the on-the-ground reality.’Maarten Scholten, Total

However, tracking supply chains is, as many GCs will tell you, no easy task. Cortés-Monroy notes: ‘If we go to the main supplier in the country they will sign our code and comply, but as you go down the various layers of the supply chain it gets more and more complicated. How do you monitor a boat in the high seas? How do you monitor a farmer subcontracted by the main supplier? It can be done but it takes a lot of effort and increased cost.’

According to Kilian Moote, project director for KnowTheChain, a Humanity United-affiliated project that helps businesses analyse supply chain risks, a further problem stems from the lack of standardised terminology. ‘Companies choose how they define human rights due diligence, which means you can have two companies in the same sector working on virtually identical supply chains: one defines forced labour as a due diligence risk, the other doesn’t. And because penalties don’t exist, no one is rewarded for defining human rights due diligence risks more expansively – quite the opposite.’

This is not just a problem for NGOs and advocacy groups who wish to see tougher accountability standards. As Google’s chief compliance officer Andy Hinton points out, the lack of clarity over human rights terminology can make a company’s ethical statements difficult to formulate. ‘Human rights is not a self-defining phrase and many of the issues are not clear cut, so when you get into it on a legal level you notice there are more than subtle differences in terms of how people view things. The dynamics that drive supply chains are complex. Outside of precise but narrow formulations of duty like the Modern Slavery Act, the issues are far from simple and will change depending on what country you’re in or what workers’ expectations are.’

Even if a company finds entities within its supply chain are not complying with its own code of conduct, knowing how to respond can be difficult. Lowry comments: ‘If we find a supplier is not meeting the standards we will commit to continuous improvement in an effort to raise all ships and only seek to disassociate as a last resort. Disassociating from a supplier is something we have to take seriously to defend our policy, but we are very conscious that we can’t impose our policy on a company – that’s not how it works.’

Indeed, the complexities of business and human rights often mean the legally obvious solution is not the ethically correct one, as Total’s legal counsel for compliance and social responsibility, Julie Vallat, notes. ‘The simplest legal solution would be to dispense with the supplier, but from an ethical point of view it isn’t good to have these subcontractors in a worse situation than before. That means you are advising on a course that is not the legally optimal solution.’

While these practical and ethical challenges will persist, GCs can take comfort from the fact that much of the reporting and monitoring requirements that fall on them can be handled by existing processes. As Moira Oliver, head of policy and chief counsel for human and digital rights at BT puts it: ‘The language of human rights can be a barrier. But GCs will find there are already mechanisms in place that cover human rights obligations within their organisations. You do need to keep in mind that you are looking at risk from the stakeholders’ point of view and it’s not the traditional approach of looking at risks to the company, but similar processes can be used to address many challenges.’

And, as HSF’s Brabant points out, the practicality of influencing a supply chain (its ‘leverage’, in the terms of the UNGPs), is only part of the picture. ‘One cannot conduct on-the-ground checks for all projects, but companies are not asked to demonstrate there are no negative impacts. They have to demonstrate they have taken reasonable steps to avoid or mitigate negative impacts. Legally speaking, the way to do this is to have the right processes. That is why lawyers are the right people to monitor supply chains.’

The long arm of the soft law

In July 2015, just after scandal-plagued Sepp Blatter resigned as FIFA president, the sports body announced it would be compulsory for commercial partners and members of its supply chain to comply with the UNGPs. Given the global reach of football, this offers a prominent example of how human rights issues are likely to be introduced to a wider legal audience. This, says John Sherman, GC and senior adviser to think tank The Shift Project and senior fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School, is evidence that the entry of human rights into contracts has the potential to challenge mainstream legal assumptions more quickly than changes in legislation.

The UNGPs – From marginal to mainstream

As far back as the early modern period of history, when the East India Company controversially wielded huge power, corporates have been involved in prominent human rights abuses. However, attempts to shape business behaviour in line with universal norms took on a new significance in the 1970s as the United Nations and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development tried to develop codes to direct companies operating in multiple jurisdictions.

Since that time, pressure for business to respect human rights has come in many forms: changing societal expectations on corporate behaviour, a growing trend toward transparency, and increasingly sophisticated tactics of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) seeking to hold companies to account. However, in promoting the issue to businesses themselves the watershed came in 2011 with the United Nations Human Rights Council’s endorsement of the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), a document consolidating earlier thinking about universal standards and adding the official imprimatur of the UN.

Drafted under the guidance of the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Business and Human Rights (and Harvard professor) John Ruggie, the UNGPs are a series of 31 principles based around three ‘pillars’ calling on states and businesses to protect, respect and remedy human rights abuses.

The UNGPs emphasise the primary duty of states to protect ‘internationally recognised human rights’, set out in a handful of international treaties with near-universal ratification. While not legally binding, the UNGPs set an expectation that businesses will respect the human rights protected in these treaties.

Soft law instruments like the UNGPs have set in train a global shift from voluntary to mandatory standards, leading to an increasing number of governments implementing the principles as part of their national action plans and progressively introducing new legislation in this area. Further, the movement toward establishing a global treaty based on the UNGPs is currently underway, with the first session of the intergovernmental working group on business and human rights taking place last year.

Lawyers play a key role in this evolution. In May 2016, the International Bar Association (IBA) adopted a Practical Guide to aid in-house and external lawyers to advise corporates on human rights matters. Various national bars have also either formally endorsed the UNGPs (as the American Bar Association did in 2012) or undertaken consultations on their implications. IBA president David Rivkin comments: ‘Corporate counsel made it very clear at the IBA in Vienna [in 2015] that they regard compliance with human rights standards as of the same importance as compliance with hard law, not least because it is often inextricably linked with complications that may have hard law consequences. Many in-house counsel will tell you that failing to acknowledge human rights can be as harmful, or more harmful, than a violation of hard law in terms of damage to reputation or its direct economic impact.’

Sherman, one of John Ruggie’s advisers during the drafting of the UNGPs, argues that this new lex mercatoria (law of merchants) is the most likely way in which human rights will cross into mainstream legal thinking.

Hudson has a similar take. ‘We have seen before with the global spread of anti-bribery and corruption laws that a particular national set of standards can quite quickly become extended to other jurisdictions because companies have created liability by signing a contract. Obligations get contractualised to the extent that asking, “are we legally obliged by the legislation that applies to us?” becomes redundant.’

Ricardo Cortés-Monroy, Nestlé

As noted already, nearly half of those surveyed had encountered human rights clauses in contracts, either in contracts issued by their own organisations or by counterparties. However, while the reference to human rights laws in contracts is spreading, GCs caution that the real impact will take several years to arrive. Lowry comments: ‘At Monsanto, anything with field labour involved will typically be covered by a human rights clause and we have recently moved to including human rights clauses with rights to audit into commercial contracts. But this is still a journey on the commercial side. It’s difficult enough to insist on something when you are the buyer. It’s even more difficult when it is a sales-side commercial relationship. We will get there, however.’

BT’s Oliver says the use of human rights clauses in certain contracts is becoming more common: ‘In a traditional contract or M&A deal it’s not one of the clauses that would feature on your standard checklist, but if you’re buying a company it’s important to understand that there may be reputational issues that wouldn’t normally filter through in your due diligence. Any well-informed counsel is making sure this gets looked at by business.’

And, for many companies, the significance of human rights clauses goes far beyond the legal enforceability of the contract. As PepsiCo’s West points out: ‘When you have relationships with hundreds of suppliers, you want to work with them and improve working conditions, but the purpose of human rights clauses goes much further than that. It’s about taking a stance as a company and showing there will be business consequences for not meeting our ethical expectations.’

In ten years’ time

The developments of the past few years suggest several routes through which human rights considerations will play an increasingly prominent role in shaping businesses’ conduct. While much of human rights law blurs the lines between black-letter law and anticipating future risks, several problems remain to be addressed. As Drimmer points out: ‘When you are trying to map a rapidly evolving field, the challenge is understanding how the patchwork of existing legislative activity meshes up with the new and developing expectations.’

However, says Ehrat, a leap into the dark may be unavoidable. ‘If you want to and have to go beyond black-letter law then you are to a certain extent going into uncharted territory. But it may be that we cannot avoid this ambiguity anymore. A proactive GC is well advised to form a view on what the law might be in a few years and engage with other stakeholders to ensure this is factored into the way the business operates.’ Or, as Brabant says: ‘A good lawyer should be paranoid and not only imagine what the law is but what it could become in the long term. Be very careful today and respect soft law principles now that could become hard law in ten years’ time.’

While it may take some time for in-house counsel to adjust to these new expectations, Cortés-Monroy is convinced it is something few will be able to avoid in the long term. ‘The issue of business and human rights is here to stay and will become increasingly important for larger organisations. I would love to see more of my GC peers engage more actively because there is a momentum and we need to make it clear to all that this is not a public affairs issue, it is a business issue and legal teams have a big role to play in defining [the] future.’

As wrenching as this shift in mindset is for lawyers, our research suggests it is a challenge the GC community in the main want to address. Asked how they view the global momentum in human rights standards, 34% saw it as a risk. The proportion that saw it as an opportunity? Sixty-six percent.