Introduction

In recent years, the governments of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have moved to reduce their reliance on hydrocarbons, designing ambitious strategic plans to develop into innovation-led economies within a 15- to 30-year horizon. One aspect of these policies has been to promote technology-backed and data-driven industries, particularly in the financial services sector.

Early results of this success can be seen in the resilience of The Dubai International Financial Center (DIFC) – the region’s flagship offshore business hub – to the economic slowdown during the pandemic. DIFC saw a 20% increase in the number of firms operating there during 2020, with fintech among the leading growth sectors. In the past financial year, the number of fintech businesses registered with the DIFC more than doubled to over 300 – roughly 10% of all businesses registered at the centre and around a third of all financial businesses.

The success of the region’s fintech sector has been the result of careful strategic planning on the part of GCC governments, many of which are offering financial, regulatory and other incentives to the world’s fintech community. In particular, the GCC is now home to a dense concentration of market-leading fintech accelerators offering financial and regulatory support along with unparalleled networking opportunities and a range of other benefits. These accelerators are already among the most sophisticated and vibrant spaces for fintech innovation on Earth, and all the signs point to even stronger support for the fintech industry from the GCC’s regulatory and governmental authorities in the coming years.

The GCC was a relatively late arrival to the fintech scene. The region’s first significant regulatory framework directed specifically at the sector emerged in January 2017 when the Central Bank of the UAE launched new licensing programmes for digital payment services. A little over four years since that time and the region has become one of the fastest growing markets for fintech innovation in the world.

The Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) anticipates that Middle Eastern-based fintech companies will raise nearly US$3bn in venture capital funding by 2022, just under a third of a projected global market funding of US$10bn. While much remains to be done for the region to become the epicentre of the global fintech industry, a closer look at the regional ecosystem reveals a considerable growth potential.

To investigate the rise of the fintech industry in the Gulf, The Legal 500 has partnered with Dubai-headquartered BSA AHMAD BIN HEZEEM & ASSOCIATES LLP (‘BSA’). Since 2001, BSA has grown to be one of the top Middle Eastern law firms, with nine offices across five countries. Their diverse team of 150 lawyers are from 35 different cultural backgrounds and speak 22 languages. BSA is a market leader in new and evolving sectors, and partners with their clients towards a sustainable and progressive future.

BSA’s fintech practice

Fintech continues to be one of the driving forces of the UAE’s big bet on technology, with an expected US$3bn in investment capital funding generated by about 465 fintech firms by 2022. The last five years has seen a true revolution in the financial services industry which was felt at every level from consumers to businesses to regulators.

BSA’s fintech practice is an exciting part of our law firm offering which has continued to grow exponentially over the last four years focusing on cutting-edge fintech matters. We are particularly sought out for our expertise in the payments space, online wealth management, blockchain technology and start-up fundraising.

partner, and head of the firm’s fintech practice

We provide services across the full spectrum of financial technology and we benefit from the ability to draw upon our extensive wider corporate, insurance, regulatory and financial experience to address the various micro-industries that form the fintech ecosystem. Our clients include financial institutions, venture capitalists and start-ups. We advise them on maximising technological innovation, enhancing and safeguarding their trade secrets and tech, and ensuring compliance with all local and international laws.

We are frequently asked by our clients to provide answers and insights as to the legislative deviations between multiple Middle Eastern jurisdictions. Consequently, we have vast experience in providing expert legal and practical business advice to start-ups and established players, regarding regulatory variations across the region and globally.

At BSA, we are also conscious that working within an ever-changing regulatory ecosystem, both from a regulatory and technological perspective, requires us to be in touch with various stakeholders. We regularly interact with regulators in various capacities: (1) when providing comments on draft legislation when and if we are brought on board in a consultatory capacity, (2) when approaching regulators on behalf of clients to enquire on the applicability and malleability of the current regulatory framework, and (3) when attempting to match new products and services to existing legislation.

While the UAE leads the way when it comes to fintech start-ups, the Middle East region as a whole is following this growth story with Saudi Arabia and Egypt boasting rich and growing industries of their own. This growth is further bolstered by a swath of new regulations in many Middle Eastern countries addressing payment regulations, stored values and digital financial services.

Several factors help position the Middle East as a hotbed for fintech activity. The Middle East presents one of the youngest populations with an estimated 28% of the population aged between 15 and 29. In addition to this, a large portion of society is deemed to be underbanked or outside of the current financial system. Governments are continuing to prioritise the digitisation of services, both public and private, which means that the Middle East is poised for continued growth in the fintech space.

We continue to have a positive outlook for growth, both from an economic and regulatory perspective. Growth opportunities have continued despite the Covid-19 pandemic which has definitely accelerated the adoption of new technologies. Some of our clients have been able to increase their spending runway, find new investors and increase their new product offerings due to the pandemic. The Middle East is home to a significantly large expatriate population which tends to use its spending power in their home countries. The last 18 months has seen this capital remain in the Middle East and fintechs have been able to capitalise on increased domestic spending.

App-led societies

When was the last time you walked into a bank? For anyone over the age of 30 in Europe or the US, the answer is likely to be “some time ago”. For the bulk of the world’s population, the answer is “never”.

The stability of the banking system and the soundness of the infrastructure across Europe and the US has been the source of many advantages, but when it comes to the development of financial technologies it has arguably become a barrier to change.

For Khalid Talukder, managing director at Dubai-based investment management company SH Capital, the GCC’s large migrant population makes it an ideal region for fintech providers looking to expand in the retail market.

‘In terms of demographics, the Gulf region is dominated by people who come from parts of the world that have not historically had strong fixed postal or telephony systems. That means the transition between the traditional ways of doing things and the digitisation of everything is far less pronounced than it would be for a European or American.

Mobile technology has become central to many Asian countries, where even in rural areas it is not uncommon to find better mobile phone coverage than Central London. Accessing services via phone apps is the established norm for most of these people, who had to become technology-savvy very quickly. They were early adopters of things like mobile wallets and facial recognition software – in countries that have a low adult literacy rate, biometrics is key.’

Just as important has been the level of fintech uptake among GCC natives. ‘In the Gulf, people could not access services if it were not for apps’, adds Khalid Talukder.

‘Concerns over data usage and storage do not really exist because digital technology and, in its broadest sense, fintech, is all people have ever known. It goes beyond banking and finance – in countries with small populations the quickest way to distribute government services is through technology and apps. It would be no exaggeration to say that the countries of the GCC are now app-led societies.’

For the GCC, an extremely wealthy and developed region that caters to both large migrant and digital-native populations, there are big opportunities to take a market-leading position. As Khalid Talukder concludes, ‘any place where people are more worried about losing their mobile phone than their wallet is a high-potential market for fintech!’

For Bachir Nawar, group chief legal and compliance officer at Dubai-based SHUAA Capital, it is already clear that the Gulf is taking a technological lead in a number of areas.

‘From biometric ID cards to how everything is done through an app, this region is lightyears ahead of some of the European markets. People here know how to develop and use technology, they have developed amazing solutions over the past 20 years and are constantly innovating. The rest of the world

is now slowly catching on’.

Bringing in the banks

A population ready to embrace new approaches to borrowing, saving and sending money gives the Gulf fintech scene a huge advantage, but winning the backing of the region’s banks will be essential if companies are going to compete in the international market.

When fintech started to boom in the early 2000s, many banks around the world instinctively opposed new entrants, questioning their compliance with the anti-money laundering regulations and a range of other regulations. Since then, major financial institutions have shifted their stance to embrace fintech, whether by developing their own solutions, investing in or acquiring start-ups, forming entire departments dedicated to digital transactions, or creating digital platform-led units to research blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI) and transaction monitoring technologies.

As a former banker, SH Capital managing director Khalid Talukder has long been an astute observer of the institutional response to the fintech challenge.

‘Banks are essentially credit institutions. Everything else they do is an ancillary service around this specific activity. The very nature of this business meant that, for many banks, spending time and resources on developing fintech was seen as a risky distraction.’

There are also purely economic reasons behind this hesitance. With many currencies across the Gulf pegged to the US dollar, high-street banks and other established institutions are understandably cautious when it comes to adopting fintech products. Ultimately, if things go wrong, the region’s banking system could put its dollar-clearing facilities in jeopardy.

However, the growing success of the fintech industry in addressing customers’ needs has left the banks with three options: Fight the fintech companies (fintechs); collaborate with them; or develop their own fintech solutions.

‘The key point is that banks want to participate in the fintech revolution’, notes Khalid Talukder. ‘They do not want their lunch to be eaten by the young upstarts. Fortunately for the banks, they have both the capital to acquire promising new entrants and the reputation and credibility to position their own offerings favourably in the market. Afterall, many of these banks have been around for 200 years. It is unsurprising that customers feel they know the industry better than companies created in the past ten years.’

Of course, it is not only the incumbents that had to revise their initial assumptions. ‘Fintech companies started off with the idea that they would make banks a thing of the past’, notes Ammar Afif, chief executive of Dubai-based instant credit and financing company Cashew Payments, which announced its own partnership with privately-owned Mashreq Bank earlier this year. ‘They soon realised that the heavy regulations applied to financial services mean this was easier said than done and have largely changed their tune to one of collaboration with regulated entities like banks.’

This thawing of earlier hostilities, adds Khalid Talukder, is a welcome change of tone.

‘Bank bashing was a bad start for fintech. Yes, banks have flaws, but they also operate at a much larger scale than start-ups, which usually only focus on one or two aspects of the whole industry. Technology offers a lot of opportunities, but scale can also be a great asset, and banks can scale up the volume of financial operations to complete millions of transactions in a split second.

The early marketing angle among fintechs was to denigrate banks, or that banks were not relevant anymore. This was not good start to their story. As in many other instances, a more collaborative approach may have been a lot better for both. And indeed, this kind of antagonistic language has now more or less disappeared, and fintech companies prefer to emphasise their accessibility, convenience or speed.’

Tarek Mogharbel, executive director and senior country counsel at J.P. Morgan UAE, also welcomes this evolution.

‘Established banks are heavily regulated entities. They are subject to various stringent regulatory requirements to prevent money laundering and other illegal processes. While this might make them less agile than corporates, such controls are perfectly justified. The fact that fintech companies understand they should always be taken into consideration when offering new products and services can only improve the industry.’

For Nejoud Al Mulaik, director at Fintech Saudi, this symbiotic relationship looks set to continue, with a number of banks across the Gulf establishing dedicated funds to invest in promising fintech companies. For the banks, the payoff is not simply accessing a more attractive front-end or the latest must-have app. By working with fintech providers the industry is looking to solve one of its biggest headaches: the cost of acquiring clients. The retail space in particular is looking to find ways to onboard new customers without having to incur the expense associated with branches, people, infrastructure, and other organisational costs. In short, many of the region’s banks now see it as a matter of survival to find efficient fintech products.

‘High-street banks and fintech companies now have a good working relationship. From my own experience, animosity between the two is a thing of the past. Banks have established capital funds dedicated to investing in the fintech sector. It is clear that banks and start-ups are partnering on all sorts of projects. Most of them are still at an early stage, but fintech is not exclusive to start-ups anymore. This close partnership has changed the face of the industry; they are working in collaboration to capture the market together.’

Raja Al Mazrouei, executive vice president at the Dubai International Financial Centre FinTech Hive, confirms this state of affairs.

‘Over the past few years, we have seen an increase in collaboration and co-creation between established banks and fintechs. In fact, the FinTech Hive accelerator programme operates based on the concept of collaboration. We scout for solutions our bank partners are seeking based on the priorities they would like to address. We find that they are very proactive in their participation every year and are excited to meet the start-ups to really make something happen. I would say banks are addressing this because not only has our list of partners increased over time, but we hear directly from the C-suite individuals of the importance of bridging the gap to better serve the market and operate more efficiently, especially as we face increasing socio-economic pressures.’

All of which means the region’s fintech market is likely to change over the coming years. As Khalid Talukder suggests, ‘it is possible that the creation of fintech start-ups will slow down in the next five years and that most investment will focus on strengthening existing businesses.

Simultaneously, banks will digitise as much as they can to lower their costs. Interest rates are not going to stay this low forever, and it will be interesting to see how the relationship between banks and fintech companies evolves when they eventually start to rise.’

Regulation

When technology takes off, the law often struggles to keep pace.

The growth of fintech across the Gulf has seen regulatory bodies playing catch-up in many areas. While the challenge of regulating emerging technologies is by no means unique to the Gulf, local dynamics have made it especially difficult to address, as one senior industry figure says confidentially:

‘Regulators across the region will often admit privately that they are a bit behind when it comes to new technology, but in this part of the world there is a very strong aversion to public loss of face. People in authority don’t like to be seen getting things wrong, whereas in other parts of the world there is more of a willingness to make mistakes and learn from them.

It is an operating environment that makes it difficult to get straightforward feedback, and things can potentially remain unclear as a result. Add to this a reluctance among expatriates to challenge authority or local norms and you can find a situation where widely-recognised problems are rarely given attention.’

However, GCC governments are aware of the importance of the fintech industry for the region’s economy, and they are committed, along with regulators, to build regulatory frameworks, and in fact a viable environment, for the market’s actors. As a result, each country has made remarkable advances in that respect.

The commitment of Middle Eastern states to pushing fintech innovation is perhaps best demonstrated by the extraordinary lengths the region’s regulators have gone in circumventing and testing their own financial rules. This is most evident in the proliferation of regulatory sandboxes – experimental spaces where both incumbents and challengers can test their products and services on the fringes of, or outside, the existing regulatory frameworks.

The region’s first regulatory sandbox was introduced by Abu Dhabi Global Market in November 2016. A year later the Dubai Financial Services Authority and the Central Bank of Bahrain followed suit with their own initiatives. Since then, the region has seen regulatory sandbox initiatives come from the Saudi Central Bank, the Central Bank of Kuwait, the Qatar Central Bank and, in the coming months, the Central Bank of Oman. Outside the GCC, sandbox initiatives have also been launched by the Central Bank of Jordan, the Central Bank of Tunisia and the Central Bank of Egypt.

The GCC-based regulators have also acknowledged the rise in investments in cryptocurrencies and cryptoassets. At present, such assets are permissible in free trade zones but restricted under mainland regulations, although rules have been put in place to supervise trading, including the UAE’s Securities and Commodities Authority’s regulation (2020) concerning cryptoasset activities.

Bachir Nawar has been monitoring the situation closely:

‘We continue to discuss this subject with the regulators, hoping that they will define the appropriate framework for investment in cryptoassets. Our hope is to eventually see an alignment between mainland laws and those of the free zones and the rest of the world, albeit learning and taking into account the key risks observed in different jurisdictions.

Cryptoassets are not something that can be stopped, and many investors are interested in them. We appreciate that they can represent a risk and that they can be complex, but for the region’s financial markets to remain credible, they need to be considered like any other form of security. This is still a work in progress, but everybody is being reasonable and showing goodwill. The complexity will no doubt remain in setting up the governance around the ‘crypto’ surge and the mitigation of money laundering.’

Fauzia Kehar, Middle East and North Africa divisional counsel at Citigroup, thinks the uncertain nature of the crypto space makes it unlikely that regulators will make a big move anytime soon:

‘The crypto space is another animal altogether – a lot of which is still unregulated and not widely understood by the public. As a result, many financial institutions are still sceptical about being first movers on this front. Frankly, I think that the industry is still deciphering how these translate into practical usage and deciding how they will be implemented.’

In the wake of their resounding success in the field, GCC countries have taken a holistic approach to fintech development in general. In addition to promulgating fintech-specific regulation, they are creating a favourable framework to ensure the sustainability of their achievements. This involves the regulation of separate but related areas, like data protection. In most cases, their data privacy and protection legislations are largely based on 1995 EU Data Protection Directive, but some jurisdictions have recently announced new GDPR-like laws that take the recent large-scale digitisation of their banking and finance industries into consideration; a new federal data protection law is anticipated to be issued by the end of 2021 in the UAE, and a Personal Data Protection Law is expected to take effect in March 2022 in Saudi Arabia, for instance.

Those we spoke to welcome these advances, but some suggest that in a following phase, reforming and simplifying existing regulatory complexity might be necessary. Take the UAE: each Emirate works independently from the others from a regulatory perspective, which restricts the ability of fintech providers who want to seamlessly cover the entire market. Even operating within a single Emirate can be a challenge: it is not uncommon for Dubai-based entities to follow guidance from the Dubai International Finance Centre (DIFC) and the Dubai Financial Services Authority (DFSA) while also paying attention to the Emirates Securities and Commodities Authority (SCA) and the Abu Dhabi Global Market Centre (ADGM).

At the regional level, countries are also competing to be recognised at the foremost hub, hoping to engage investors and develop their own companies.

‘Competition within a market is always positive, it pushes companies to improve,’ comments Nejoud Al Mulaik, ‘but having to navigate between multiple jurisdictions is always a challenge. The GCC is made of sovereign states, each of which retains all legislative power, of course, but they should be wary of imposing too many hurdles to the international expansion of successful companies. Saudi, which is the largest regional economy, has unified financial regulations across the country. Every day we see how important an asset unity and cohesion is, and we always bear this in mind.’ As such, regulatory simplification and harmonisation came out as the top item on the wish list of entrepreneurs and investors. Whether this takes the form of a Gulf equivalent to the European Single Euro Payment Area (SEPA) – a collaborative arrangement overseeing all regulation, simplifying banking transactions and harmonising financial services or passporting rules – or something more modest, a new approach to regulation is now on the policy agenda. There is a growing awareness of this need across the region’s governments. Several GCC states are reportedly in discussions over potential common regulatory standards, and developments are being closely monitored by the main market players.

However, says Bachir Nawar, all positives of the Gulf regulatory situation are often overlooked.

‘Every entrepreneur in the world will tell you that regulators are, by definition, an obstacle, but in the Gulf a productive relationship has developed between the two sides. Entrepreneurs no longer accept that the answer to an application can be a simple “no” – particularly if they believe there is benefit to the region in making a change – and regulators have created an environment that allows us to collaborate with and challenge them so that business can be improved safely and within the boundaries they have set.

Regulators understand that if you want to be pioneers, you must be flexible. Somehow, as an industry, we have mastered the delicate art of challenging the regulators when their rules become hurdles. At the same time, we support them as much as we can by providing all the necessary information for them to understand the market.

Over the years, companies have forged excellent trust with the regulators. They know that innovation is in our genes, that our purpose is to create disruptive changes, but that we will never try to bypass their rules. All the processes have now been made faster and a lot more fluid in the whole of the Middle East, and we will continue to work with the regulators on improving them.’

Nejoud Al Mulaik makes similar observations. ‘The regulatory process takes time, but it is part of the overall efforts to support the transformation of the sector. In Saudi, the regulatory framework and licensing system have continuously and efficiently been improved, thereby protecting consumers, but also creating opportunities for start-ups and opening windows to test innovative solutions.’

Citigroup’s Fauzia Kehar has also been impressed by regional regulators’ commitment to improving the business environment.

‘There is a lot of work being done in the UAE tech space in general. New regulations are being issued on things such as payment systems, money services providers, and digital licenses.

Despite the regulatory process still developing, the government, companies and sometimes consumers themselves are being very supportive. In fact, the different regulatory bodies have made great progress

in the last few years.’

Point de Vue: A lawyer’s perspective on legal and regulatory developments in the UAE and Middle East

With his expertise and experience of over ten years at BSA, Nadim Bardawil puts the recent legal developments in the UAE and the Middle East for the regulation of the fintech sector into perspective and explains the regulatory changes expected to be introduced later this year.

Fulfilling the digitisation vision of many countries in the Middle East, the fintech industry has experienced unparalleled growth over the last five years. As Middle Eastern society slowly but surely moves away from an exclusive focus on bricks-and-mortar businesses, fintech entities are capitalising by offering online and on-the-go solutions.

Banks and financial providers are doing far more of their business online, whether through apps on smartphones, or via secure portals that are accessible by users from anywhere in the world. This approach has given customers and consumers a far greater degree of freedom, making it easier to access their banking and money (no more visits to the bank manager, now you can Zoom him/her any time), and greater expectations of the accessibility of a wider range of services.

In the UAE, the rise of fintech has been phenomenal. Fitting in with the ethos of a young and vibrant population, digital finance has been embraced as part of everyday life. It’s quick, it’s easy, and it makes the consumer feel that they’re in charge of their money in a far more intimate and personalised way. The concept of an “e-wallet” appeals to a generation who have come to rely on their smart devices for everyday life, from picking up emails on the go, to accessing the internet while making the daily commute. It fits in with the rapidly developing economies of the UAE, and the region’s more prominent position on the world stage as well as a staggering young population.

Changing regulatory frameworks are impacting business growth

In tandem with the above, regulators in the region have passed several forward-thinking legislations to address the growing gamut of products and services offered by fintech providers.

In the UAE, the Central Bank issued an updated stored value framework repealing the previous legislation passed in 2017. The Central Bank also has plans to issue a stand-alone payment service provider legislation which is expected to be introduced within the coming months. In the DIFC, the provision of a money services framework by the DFSA has allowed for a new set of business ventures to launch in the

financial centre.

In Saudi Arabia, the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (‘SAMA’) issued the Payment Service Provider Regulations in January 2020 which was followed by SAMA announcing its Open Banking Policy in 2021. These initiatives are in line with SAMA promoting the country as a hub for fintech and encouraging the use of emerging and nascent technologies in the country. Following suit, Egypt passed new legislation in September 2020 allowing the Central Bank to issue licenses to fintech entities. This legislation has further encouraged the use of new technologies in Egypt, including the ability to provide licenses for the issuance of cryptocurrencies.

The impact of these changing regulations has yet to be fully felt with consumers, but we can already clearly see the impact with non-financial services entities such as e-commerce platforms, ride-hailing platforms and others integrating fintech services in their verticals. It is thanks to these regulations that the provision of financial services using technology has become more accessible.

Rather than creating barriers that prevent independent financial providers to enter the market, a more flexible attitude to digital financial services has opened the sector up to the next generation of money providers. Effectively, ‘old school’ banks now sit alongside fintech start-ups in the same sector. The obvious winner is the consumer, who now has a greater choice.

An international reach

While several world-class accelerators continue to encourage start-up and venture building in the Middle East, we are also seeing international players enter the market either by way of applying for licenses or by way of acquiring existing local players. The UAE in particular has been able to benefit from having the DIFC and the ADGM as financial centres which are founded on English law and boasting comprehensive applicable regulations.

The transition to fintech represents a cultural shift in the Middle East, but there are still issues to contend with. Take-up among older people for online financial apps, services and provision are still some way behind those in the younger, and especially the 18-34, age group. But fintechs are recognising that all of their customers matter and are adapting their products to suit multi-generational groups.

While clearly there is work to be done to grow the ecosystem further, this has not stopped a continued flow of global investment flooding the region. Today, an estimated one in four investment deals in the Middle East have been made in the fintech sector. Venture capital firms and institutional investors are increasingly looking to establish permanent set-ups in the region while regional sovereign-backed funds are putting more capital in play for regional ventures as they see the growth potential.

What’s next?

We are witnessing the next generation in financial provision, with money services from insurance and banking through to telecoms, to payment services and wealth management all available via apps or online portals. This has made finance more accessible for everyday users, especially those users who may have had limited or no accessibility in the past.

We continue to see regulators actively working to provide an updated legislative framework to keep up with the times. As an example, the DFSA has announced that it will be launching a consultation paper addressing the regulation of security tokens and other cryptoassets by the end of 2021. It is encouraging to see regulators take a proactive approach and consult with stakeholders to put new regulations into place early on so that the financial services sector can continue to provide a diverse and dynamic range of options that fit in with the forward-thinking ethos of the region.

Innovative ideas will always come along, and the regulatory bodies will have to adapt and change to a new era of doing business.

We expect that the coming year will see not just a surge of new licences issued by regulatory bodies, but the continued growth of the digital financial marketplace in a well-regulated and transparent way that inspires trust and greater take-up among both businesses and individual consumers.

Growing the ecosystem

The impact of nationalisation policies on the Gulf labour market has long been a hot topic among multinationals and start-ups operating across the GCC.

‘When the initiative was first introduced, it was initially difficult to meet these expectations’, comments Bachir Nawar of SHUAA Capital. ‘Many companies had very specific HR needs and were not used to the idea. Emirati business leaders and entrepreneurs also pointed out that they struggled to motivate the younger generation when it came to work. However, we all understood what the government was trying to achieve with this measure, and we all worked hard to make it a success.’

In recent years, says Bachir Nawar, the fruits of this policy have become increasingly evident.

‘SHUAA Capital has managed to attract and nurture the national talents we need. These people have been part of our success.

Today, private companies are no longer looking at this issue as a problem. In fact, because the selection of UAE nationals became so rigorous, it sparked Emiratis to get better degrees and improve their expertise. They have now exceeded all expectations. The whole business scene is changing and in the next few years we will see far more Emiratis leading in most senior corporate and technical positions.’

Ammar Afif, of Cashew Payments, agrees that many of the high-skilled jobs currently occupied by expatriates will soon be filled a younger generation of domestic talent.

‘I see a lot of young people that go abroad to study, get internships, and see what is being done in other countries. They are keen technology users themselves and they want to make a difference. This all leads to them being very involved in the technology industry in the next few years. In fact, they are settling into key roles as we speak.’

At the same time, this new generation is proving to be more open to foreign influence within the region. As Bachir Nawar comments, there are already signs of this shift within the region’s free zones.

‘One good thing about this region is that people here do not want to be left behind. Governments across the Gulf have encouraged investors to focus on fintech, giving a wake-up call to the region’s strategic approach. We are heading in the right direction, and there will soon be better synergy between people who can ask the right questions and highlight the areas where things can be improved, and the people who know how things work and have the relevant networks and connections. Conditions are ripe and there are many incentives for investors to come here.’

Funding and the fintech ecosystem

In the US or European model of tech start-ups, founders typically look to venture capitalists for early-stage funding. However, the dynamic of the ecosystem is slightly different in the Gulf, in the sense that it is more targeted.

‘From my experience in the region,’ says Bachir Nawar, ‘I would say that it is more than money that dictates what kind of industry, and the discipline that needs to be followed. The growth of the fintech sector is more strategic than anywhere else; investing in the industry here has become a normal aspect of wealth management.’

Vishal Koovejee, associate general counsel at SHUAA Capital, concurs and he adds that the UAE tech-ecosystem is not only different from the Western one, but it is unique in the whole of the Middle East.

The investor-entrepreneur relationship is different here than it is in Silicon Valley or even in other neighbouring countries: the fact that investing in tech is often a way to diversify their portfolio, investors want more control over the development of the start-up that they put their money into. As a result, the SAFE (simple agreement for future equity) agreements tend to be a lot more prescriptive for the companies, as when they still are at the funding stage, they do not have much leverage to negotiate properly. This aspect of business adds yet another layer of complexity for the layman.’

Ammar Afif agrees that the difference between the Western and the Middle Eastern investment strategies lies in the amount of risk taken at the early stages of start-up funding. ‘Whilst the US is years ahead in terms of investment, there is only so much money available at the beginning of a project. Most venture capitalists in the US, Europe and Australia realise that the initial bet on a company should largely be based on who the team is comprised of and what the ideas are. If it looks serious enough, then they will put some money into it, and see where it goes, but I think that they expect a certain rate of failure. I do not know what the exact numbers are, but for ten investments they make, five will probably end up failing completely, and from the other five, maybe two or three will bring a little bit of return. Only one or two, at most, will become home runs or make the return for the initial investment. This has been the concept in the West for many years now. In the Gulf, however, until recently there has been an approach with venture capitalists looking for solid projects’, says Ammar Afif. ‘The criteria for defining if a project may be a success is different, they consider deals won and revenue generated. Here, one of the best options for start-ups to get initial funding is actually looking to individual investors.’

These very specific business conditions explain why, for a long time, the Middle Eastern fintech scene was characterised by regional, if not nation-specific challenges and opportunities. However, as fintech entrepreneurs have improved their products and established their brands, they are beginning to adopt a more international approach to their development. ‘When asked about the internationalisation of the Middle Eastern tech market, I like to take Anghami, for which SHUAA recently raised funds, as an example’, explains Bachir Nawar. ‘Anghami is a direct competitor to Spotify, so not a fintech company per se, but earlier this year, it became the first Arab technology company to be listed on the Nasdaq. It was created in Beirut, then moved to Abu Dhabi, where it is now headquartered, and was supported by the Abu Dhabi Investment Office (ADIO). Another example would be Alef Education, an Abu Dhabi-based edtech (education technology) company. As to the fintech industry specifically, I am not pretending that we are as advanced as the US or any other European country, like Denmark, that has an institutionalised system that supports the fintech industry, but Middle Eastern companies are undoubtedly propelling themselves beyond the Arab world and are set to compete on the international scene.’

For Raja Al Mazrouei, GCC start-ups are destined to remain partially focused on Gulf-specific challenges and opportunities, but they are in a very favourable position to expand in the future.

‘On the one hand, our start-ups offer focused solutions – especially when it comes to Islamic fintech and regtech (regulatory technology), two areas that are specific to this region and depend on our laws, regulations, and culture. On the other hand, they also offer other fintech solutions that cut across these characteristics and are solving wider challenges across various markets and geographies. This rollout to different markets is a testament to the adaptability of the solutions but also an indicator of some common denominator challenges that the financial industry faces.’

This movement, according to Vishal Koovejee, might only be in its infancy but he anticipates further development for the regional fintech start-ups in the years to come. ‘Our companies are very successful; they are raising the interest of overseas investors, which can open doors really quickly. This is particularly noticeable in the sector of AI, where Arab start-ups are ready to compete on the international stage, and should do so in the next couple of years.’

Ammar Afif concurs and provides some perspective on this. ‘Fintech is one of the sectors that has really boomed lately. Most products have rapidly become popular with consumers, very popular with merchants internationally, and particularly in the Gulf market. The Middle East, in general, is a great market: there are talented people, internationally-recognised experts, it is becoming a very interesting place to set up a company and launch products. The UAE is formidable hub, but there are other huge markets outside of it. I cannot name them all, but Egypt is another one, with an enormous population. Nowadays, most fintech companies, including Cashew Payments, are introducing their products in the region and then adapting it for specific markets such as Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, etc.’

In this respect, much like Khalid Talukder and Ammar Afif, Bachir Nawar and Vishal Koovejee forecast a coming together of banks and fintech companies in the short term, with the objective of developing faster and further. ‘At the moment, only a few Arab companies are truly global. In the next four to five years, however, the banking and the financial sector is the first to jump on the bandwagon of our companies’ international development. To some extent, banks have been preparing for this. Many have either spun off some of their subsidiaries into specific fintech-driven industries – be it an investment management, or be it private wealth, for instance. The digital transformation in this part of the word is primarily driven by capital, therefore banks will play and pioneer every growth to come.’

These investments are also facilitated by the legal and regulatory environment promoted by the local governments.

The Emirates are home to the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) and the DIFC respectively, two of the several UAE international financial centres and free trade zones that are particularly relevant to the fintech sector.

These two free zones operate with their own specific systems. There, start-ups have two options as to how they want to develop. They can get a partial license that allows them to continue as a normal company providing they can self-fund.

The only condition is that they are placed in a sandbox for a year and are mentored and guided until they can fly with their own wings.

Alternatively they can get a fully-fledged license and be backed by investors immediately. There are other bodies in the UAE that have technology and fintech as part of their remits, specifically – the Abu Dhabi Developmental Holding Company (ADQ) would be a good example – and their mission is to support entities and start-ups in this sector only.

According to them, this development will be encouraged by specific legal changes that are adopted in several countries in the region – especially in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. ‘Governments are aware of the many opportunities that exist, and they are being proactive. They are working on very practical measures, like lowering, subsidising or delaying the payment of licensing fees for small start-ups. They are also in the process of simplifying the general bureaucratic requirements to facilitate the setting-up of a company, for instance. But they are capable of thinking on a bigger scale. Particularly, they are making it possible for anyone – providing they comply with the law – to own a license in their jurisdiction, but work remotely from any other location. In times like a pandemic, such a measure can literally save the industry. They are also relaxing the visa approval process for fintech and technology professionals. The governments are putting themselves in the best conditions possible to attract the talent their countries need. Fintech professionals are already taking advantage of these changes for the better.’

In addition, while incentivising local companies to hire nationals, ‘the authorities have relaxed the requirement for foreigners to have shareholding in most companies and even full ownership. Of course, strategic and sensitive industries such as oil and gas remain protected and managed by nationals, but overall, these measures will attract investments. Some will go directly to fintech start-ups, others will indirectly benefit the sector. In any case, the UAE and most Gulf countries in general are known for being asset management and banking hubs. The region is such an important investment, private banking and retail banking platform, that if it attracts investments, fintech will grow one way or another. The grounds for it have been paved and I think it is a fertile soil for the growth of the industry.’

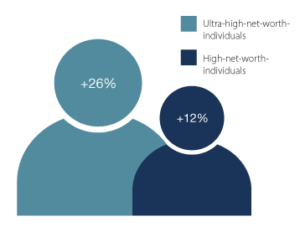

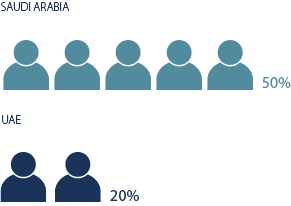

The governments’ strategies to draw investors seem conclusive. ‘Studies show’, says Bachir Nawar, ‘that by 2025, the number of high-net-worth and ultra-high-net-worth individuals, will increase by an average of 12% and 26% respectively across the Middle East, with 50% of these ultra-high-net-worth individuals residing in Saudi Arabia, and 20% in the UAE.’

This influx is expected to generate even more opportunities. ‘These affluent investors are significantly underserved’, continues Bachir Nawar. ‘And because their number is growing so fast, it is virtually impossible to build all the traditional banking and finance infrastructure for them. Digitising the whole financial industry has almost become inevitable. Many people have heard of fintech, but colossal changes will happen soon. The business will change to a level where the technology will command the investment management industry, rather than just supporting it. SHUAA Capital is preparing for this, and I am sure all our competitors are as well. In June this year, we announced the appointment of a head of digital transformation, because we, as a company, must lead the trend – we are working on a digital wealth platform that is still off the record – and are prepared to handle the disruptions to come.’

ultra-high-net-worth-individuals by 2025

According to Bachir Nawar and Vishal Koovejee, many of these digital transformations have been accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, but were, in any event, ineluctable. ‘The whole finance industry is heading towards mass digitisation. In a matter of two to three years, the sector will probably be largely manless. The pandemic, regardless of how troublesome it was, was a real test, and everything went well; people have taken full advantage of digital products and relied on fintech for all sorts of operations. The very nature of the industry will change to the point that it will be able to offer incredibly innovative self-serving and self-fulfilling digitised or robotised services at a scale that was not conceivable until recently. However, manlessness does not mean that we will not need people any longer.’

Ammar Afif agrees that digitisation will progress rapidly and exponentially. ‘The push to digitisation is happening, and it is happening in new ways and in different areas. It affects banking and fintech, but not only this; it is everywhere: in healthcare, in transportation, and even in the food industry. Digitisation is happening everywhere in the world, but the GCC members and the rest of Middle East are ahead of things in terms of research and in terms of its implementation. Having an edge is very important, because digitisation draws investments, and other countries are trying to catch up, sometimes successfully. Pakistan, for example, has recently developed its fintech industry which has attracted a couple of hundred million-dollar investments in the past six to nine months. It is wonderful, because this creates a healthy rivalry which can only result in the development of better products. And that is a good thing, because technology can make a big difference in people’s lives: they can invest or manage their assets more efficiently, have better mortgage options or if they have a company, there are very good KYC (know your customer) services, for instance. Investors see that there is a demand for more fintech, and that people learn how to use new products very quickly: digital banks and crypto have boomed, lately. In the years to come, there will be a lot of competition, because fintech is a hot market, and will continue to be so for a long time.’

For Raja Al Mazrouei, ‘the industry makes an effort to provide solutions that are always in line with the public, which explains why investments in the region’s fintech sector are on an upward trajectory. Fintech start-ups from the FinTech Hive raised close to US$300m in funding, and these funding rounds continue to be led by institutional investors, venture capitals, and angels across a variety of fundraising phases.’

Fintech Saudi’s Nejoud Al Mulaik reinforces this analysis. ‘In 2020 and 2021, the Covid-19 pandemic slowed down the global economy. I understand that it harmed several verticals within the financial technology industry in Europe and North America. However, because Saudi Arabia, and in fact the Gulf in general, is still an expanding market, we have seen a spike in the number of deals, and investments kept coming in. Venture capitalists showed interest and we have attracted foreign direct investment from around the world, and there is evidence that the region will remain attractive long after the pandemic has subsided.’

In Saudi Arabia, the diversification and digitalisation of the financial sector are part of the government-led Vision 2030 programme, which aims at making the Kingdom a ‘vibrant society, a thriving economy and an ambitious nation’. The programme includes the re-thinking of the whole financial sector and its improvement through the use of financial technologies built around the market’s needs and opportunities, sparking Nejoud Al Mulaik to acknowledge that ‘the growth the fintech sector has experienced is a combination of significant investments and deliberate policies.’

Regardless of how much investment flows in the industry, however, Ammar Afif confirms that most fintech start-ups nowadays want to have a positive impact on society. ‘A lot of people see Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) as extending credit only. It is true that we exist to provide more credit to consumers, but one of our foundation principles is that we would like to do so in a responsible manner. We do not want this credit to be used for the consumption of material goods only. Our main focus is not on how we can help consumers to get the next iPhone or a better laptop or more expensive fashion accessories; we want to take financing to a further level. We want people to use our services to help them pay for their education, for instance. Rather than paying school fees up front, they would be able to split them over instalments. We want to help people travel and enrich themselves culturally. This entails spreading their ticket costs over payments. Healthcare is another sector we are looking at. Our goal is to work with banks and other lending entities to cover all the vital sectors that people might not have access to because of cost. Many things are still untapped. We are exploring them, but we want things to be done in a responsible way. Fortunately, all signs suggest that in the next few years, this will be possible.’

GCC Accelerators

Bahrain

Bahrain

Bahrain FinTech Bay (BFB) is among the leading fintech hubs in the region. Established in 2018, it aims to accelerate the development of local early-stage fintech companies while also helping international fintechs establish a presence in Bahrain.

BFB has so far incubated over 50 fintechs and has supported a number of accelerator programmes. Its successes include Rain, the first cryptocurrency platform in the MENA region and CoinMENA, a Sharia-compliant cryptocurrency exchange licenced and regulated by the Central Bank of Bahrain.

It has also partnered with the Tamkeen labour fund to develop the National FinTech Talent Programme offering promising candidates a six-month internship along with mentorship from BFB member organisations.

In early 2021, BFB signed a cooperation agreement with Israeli fintech association FinTech Aviv that will see both institutions work to strengthen and develop the regional ecosystem.

Kuwait

Home to a well-established banking and finance sector – the Kuwait Investment Authority being the world’s oldest sovereign wealth fund – Kuwait created a regulatory sandbox framework and a dedicated fintech unit in November 2018 via the country’s central bank (CBK).

In 2019, the Kuwaiti government announced the creation of a US$200m fund for technology and fintech investments, prompting the development of the industry, particularly as regards wealthtech (wealth management technology) and insurtech (insurance technology).

Oman

As part of its Vision 2040 strategy, the Sultanate of Oman has committed to supporting digital transformation across its industries. Support for fintech has come from the Oman Startup Hub (OSH), a platform for start-ups, investors, advisors, and entrepreneurs to connect, collaborate and learn about the innovation ecosystem in Oman. In 2019, Muscat Bank, the country’s largest financial institution, announced a US$100m fintech investment programme, while the Oman Technology Fund (OTF) is also likely to extend its backing to the fintech sector.

When the Central Bank of Oman (CBO) launched the Fintech Regulatory Sandbox (FRS) in December 2021, the Sultanate made a great step forward in the implementation of the financial component of its National Programme for Enhancing Economic Diversification.

Committed to offer unique fintech opportunities, CBO pledged Islamic-compliant solutions at the heart of its ecosystem.

Qatar

The most recent arrival on the GCC fintech scene has been Qatar FinTech Hub (QFTH). Founded by Qatar Development Bank, QFTH aims to support the growth of the fintech industry in Qatar. It offers a 12-week Incubator programme for entrepreneurs and early-stage fintechs and an Accelerator programme for more mature fintechs looking to expand globally.

Wave 1 of QFTH’s Incubator and Accelerator programs launched in 2020 with a focus on payments solutions, while Wave 2 launched in summer 2021 with 11 early-stage start-ups and 11 mature fintechs participating. A third wave, focusing on embedded finance and techfin (established technology companies offering financial products), will begin later this year.

While the QFTH aims to promote the fintech sector in Qatar, its support is very much open to international applicants. The first wave saw 12 internationally-headquartered fintechs join seven Qatari start-ups, while in the second wave 19 international fintechs were joined by just three Qatar-based applicants.

The QFTH’s regulator-backed programs offer access to Qatar Development Bank’s QR365m (US$100m) venture capital fund, mentorship from QFTH’s international network, and regulatory support including registration with the Qatar Financial Centre. This regulatory support will soon include access to Qatar Central Bank’s regulatory sandbox, a planned initiative that will allow fintechs a safe and controlled space to test their solutions under relaxed regulatory requirements.

Saudi Arabia

Fintech Saudi was established in April 2018 as a joint initiative between the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) and the Capital Market Authority (CMA) to support start-ups through talent development in partnership with universities and infrastructure building. In parallel, SAMA and CMA launched several initiatives, including the Fintech Lab, to act as sandboxes and platforms for entrepreneurs to suggest regulations.

‘Fintech Saudi’s main remit is to assist start-ups in every possible way’, says Nejoud Al Mulaik. ‘We work on accelerating programmes to encourage the creation of new companies, and we keep providing support long after they can fly with their own wings. For instance, we think that the most likely scenario for the future is an increase in the number of mergers between fintech companies and start-up acquisitions by banks, and we are ready to provide counselling on this.’

Other accelerators have since been launched, like Misk 500, which is extending its influence in the Arab world, and Blossom, which focuses on female entrepreneurship in the Kingdom, for instance.

Expected to reach over US$30bn in transaction value by 2023, the Saudi fintech market has grown much faster than originally planned by SAMA and has generated interest in the UK’s financial services sector, a global reference point in the area, resulting in bilateral talks on potential cooperation opportunities.

UAE

In 2017 the Dubai International Financial Center (DIFC) cemented its position by launching FinTech Hive, the first and largest fintech accelerator in the Middle East, Africa and Southeast Asia region. Now among the ten largest fintech hubs globally, FinTech Hive offers early and growth-stage companies the chance to work with leading financial institutions and technology companies and compete for funding, including

the DIFC’s own US$100m dedicated fintech fund.

Not to be outdone, Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) has also made significant moves to foster a strong fintech ecosystem through its RegLab sandbox, a specially-tailored regulatory framework that allows innovative businesses to test their offerings outside the regulatory requirements that would otherwise apply to financial services firms. It has also partnered with Plug and Play, the world’s largest early-stage investor, accelerator, and corporate innovation platform and the Abu Dhabi Investment Office to launch a fintech accelerator programme. Finally, ADGM is a key partner of Hub71, an initiative of His Highness Sheikh Khalid bin Zayed Al Nahyan, which launched in 2019 with AED1bn (around US$270m) in funding. Over 100 start-ups have so far been supported by Hub71.

Focus on

Focus on: Cashew Payments

A Buy Now Pay Later company. Buy Now Pay Later is growing in the Middle East and emerging markets.

‘Buy Now Pay Later’, says Ammar Afif, ‘gives consumers and businesses another payment option when cash, a debit or a credit card would be used. It is an alternative whereby one can pay over instalments from an existing debit card, credit card or bank account. It generally comes with no cost for the payer and enhances customer experience.’

Focus on: FinTech Hive

‘The FinTech Hive is the first and largest financial technology accelerator in the MENA region’, explains Raja Al Mazrouei. ‘It supports the development and growth of fintechs, insurtechs, regtechs, and Islamic fintechs. We enable start-ups in providing them a platform to showcase their products and solutions in front of the region’s most prominent financial institutions. The FinTech Hive is the hub for fintech talent development, incubation and acceleration programs, funding and investment, and business collaboration and co-creation opportunities for the key players in the MENA region.’

Focus on: Fintech Saudi

Launched in April 2018 by the Saudi Central Bank to animate and organise the Kingdom’s fintech industry.

‘Saudi Arabia is very advanced in terms of digital infrastructure and our market is particularly competitive,’ comments Nejoud Al Mulaik. ‘We are keen to work in collaboration with other GCC members to improve the overall fintech industry.’

Focus on: SH Capital

As a prime broker, SH Capital ‘aggregates the world’s largest asset management investment funds, before allowing them to be distributed to target mid-market and SME corporates that were historically looking for high yield products other than their own sort of banking account interest rates,’ explains Khalid Talukder.

Focus on: SHUAA Capital psc (DFM: SHUAA)

A leading asset management and investment banking platform, with c. US$14bn in assets under management.

Listed on the Dubai Financial Market.

The asset management segment, one of the region’s largest, manages real estate funds and projects, investment portfolios and funds in the regional equities, fixed income and credit markets. It also provides investment solutions to clients, with a focus on alternative investment strategies.

The investment banking segment provides corporate finance advisory, transaction services, private placement, public offerings of equity and debt securities, while also creating market liquidity on OTC fixed income products.

The firm is regulated as a financial investment company by the Securities and Commodities Authority.

With the kind contributions of:

Bahrain

Bahrain