The rise and rise of Chinese investment in Latin America

Last year marked the 40th anniversary of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms. The results of these reforms has not only been to grow China’s domestic economy but to transform its influence as an economic actor on the world stage.

In 2016, for the first time in modern history, China became a net overseas investor. That year, while global outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI) fell by 2% China’s investments surged by nearly 35%. The trend shows no sign of stopping. As China becomes an increasingly important source of financing globally the economic, political and legal map is being redrawn. For countries in the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) region, the impact has been striking.

Since 2000, annual trade between China and Latin America has grown from $12bn to over $300bn, making China the second biggest investor in the region while displacing the US as the leading trade partner to countries such as Brazil and Chile. China’s two global policy banks – the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China – have issued more than $150bn in loans issues to LAC countries and state-owned firms over the past 15 years, outstripping the combined loans issued by the World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank and the CAF Development Bank of Latin America.

The steady rise of China’s investments in Latin America may have produced some eye-catching statistics, but for Chinese lawyers working in the region there are even clearer indicators of the shifting geopolitical sands.

‘When I landed at the airport in Lima the first advertisement I saw was in Chinese’, says Charles Wu, a Beijing-based partner at Zhong Lun law firm. ‘There are quite a number of Chinese businesses here now interacting with each other and forming communities. It really feels like something big is happening.’

The density of Chinese businesses operating in Latin America means a trip across the Pacific is rarely a step into the unknown. ‘It was a bit of an eye-opener for me’, says Paul Wee of Norton Rose Fulbright’s Beijing office, recalling his first trip to Caracas. ‘I was advised to stay in the hotel, but my clients had a base there and life revolved around the expat community. I ate Chinese food and spoke Chinese. It was almost as if I hadn’t left Beijing.’

In the last decade, more than 2,000 Chinese companies have commenced operations in Latin America, generating nearly two million jobs for locals. While the community of lawyers servicing this cross-border trade has grown, it is, says Wu, ‘still small enough for those of us who work in the area to feel we know everyone’. But as the number of Chinese businesses operating in Latin America rises, firms are begging to sense the opportunity.

‘China to LatAm is extremely hot and it’s an area we are expecting to grow massively’, says Nicole Pineda, a partner at Harneys’ Cayman office specialising in inward and outward bound Latin American investments with a particular focus on structured finance and infrastructure finance transactions. ‘A lot of firms are setting up China to LatAm desks, and everyone is jumping on the bandwagon. The economic significance of it is probably still rather limited compared to other specialist desks, and until the work monetises with volume a lot of the interest is likely to be exploratory, but it is getting to a point where you could consider China to Latin America trade a real business line for lots of firms.’

From farms to fibre optic cables

Miguel Zaldivar, regional chief executive for Asia Pacific and Middle East at Hogan Lovells, has seen the rise of Chinese money in Latin America first hand. The firm has acted on over $100bn of Latin America-related infrastructure development financings in recent years, with Zaldivar closing a number of these deals, including the largest development financings in the history of Ecuador and Honduras.

‘I worked on a lot of financings for refineries and ports in the early 2000s and they were all run out of New York or London’, he recalls. ‘Around the time of the collapse of Lehman, US and European companies started getting displaced from infrastructure projects. By 2010, Chinese companies had started taking the lead on infrastructure financing. There came a point where I was spending around half of my year in Beijing to work on these matters, so I really had a front-row seat when it came to the shifting of power in terms of development financing.’

In these early years of China’s Latin America investment boom attention was directed primarily to satisfying the country’s growing demand for commodities and raw materials, with soybeans, metals and minerals and hydrocarbons accounting for 70% of its imports. A lot has changed in the last decade, but obtaining raw materials remains a key concern of Chinese investors.

‘With Latin American markets opened by the first wave of investments, private entities have found it to be an attractive destination to invest.’

‘The interest we are seeing is still focused on resources, which makes sense in the context of Chinese companies’ need to secure their supply chains’, says Lin Zhong of EY Chen & Co. ‘For example, China is the biggest manufacturer of lithium batteries and needs a lot of relatively rare metals and chemicals. Going upstream to acquire targets is a vital part of these companies’ continuity plans for the coming decade.’

However, Chinese investors are increasingly pursuing opportunities in transport, finance, electricity generation and transmission, information and communications technology, and alternative energy services. Xinyue Ma, China Research and Project Leader at the Global Development Policy Center at Boston University, has been collecting data on China’s trade with Latin America for a number of years. In recent years, she says, the focus of these investments has shifted dramatically. ‘The service market has been growing and recent figures show that services account for more than 70% of investments.’

Investment may be on the rise, but says, Charles Wu, of Zhong Lun, it must be put into perspective. ‘[Latin America] is an important market but it is not as important as North America or the EU. Law firms from the PRC are still primarily working on large infrastructure and mining projects, and most of the investor base is large state-owned enterprises or large public companies looking to expand their main business and find mineral resources in Latin America. That’s not to say that there aren’t smaller investments taking place, and we do occasionally work on matters for tech companies, but the frequency is nowhere near as high as in the US and Europe.’

Monica Sun, a partner in Herbert Smith Freehills’ Beijing office, adds: ‘While Latin America is growing in terms of Chinese interest we need to get this in perspective. Southeast Asia, for instance, sees far more interest still; [Latin America] is one market among many and is not by any means the dominant investment destination for Chinese clients.’

It is worth noting that many of the most ambitious Chinese-backed projects never got off the ground. Plans to build a canal through Nicaragua connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, or a railway crossing the Amazon and Andes caught attention but have so far led to nothing.

There are also signs that the rise in Chinese investment may already be slowing. ‘The whole background of outbound investments is decreasing, says Molly Su, a Shanghai-based partner with King & Wood Mallesons who has been working on outbound financing projects for the past 13 years. ‘State-owned enterprises are more cautious, especially in the mining and thermal power sectors, policy banks have been tightening their credit lines, and foreign currency exchange controls in China mean it is becoming increasingly difficult for Chinese companies to remit money out of the country. While some specialised sectors such as hi-tech, medical or pharmaceutical investments may be seeing a rise, overall the numbers have been heading downward, particularly in terms of Latin America. However, project-based investments by large Chinese entities tend not to be one-offs. Once you release the funds and build up the personnel and infrastructure it means you are committed to the market. That means we can expect to see continued activity for the years to come.’

Following the financial crisis of 2008, China undertook a huge stimulus programme aimed at boosting its construction and infrastructure sectors. This found a political ally in the Belt and Road initiative, seeking to put this excess capacity to productive use in foreign markets. However, in recent years there has been a new policy aimed at restricting the outflow of capital.

Off the beaten track: Belt and Road in Latin America

As the number and significance of China’s projects in Latin America continues to grow, the continent is becoming an increasingly important part of the Belt and Road initiative (BRI). Launched in 2013 as a plan to create an economic corridor across Europe and Asia, BRI seeks to strengthen trade and investment between China and over 60 countries, opening up markets that are home to over 60% of the world’s population. So far 131 countries have signed up to the initiative, sharing almost $600bn of new investments between them.

China’s interest in extending the scheme more broadly is obvious. For a country that has already built high-speed railroads connecting many of its major cities, there is increasingly a sense that meeting infrastructure needs at home is not the priority it once was. For the huge number of businesses that were directed to meeting these needs, finding new markets is becoming increasingly important.

Though geographically remote from China, Latin America has been earmarked as the Pacific line of the Road. Countries across the region were formally invited to participate in the initiative during China’s meeting with the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) in Santiago, Chile in January 2018. Shortly after this meeting Panama established diplomatic relations with China and became the first country in the region to sign a cooperation agreement under BRI. Since then, a further six nations in the region have signed up to the initiative, including Chile and Peru, while countries such as Ecuador and Cuba have signed formal cooperation agreements with a view to joining at a later date.

Latin America’s largest economies – Argentina, Brazil and Mexico – have yet to join BRI, though there is some ambiguity over what “joining” even means. Argentina and Brazil, for example, have signed comprehensive bilateral cooperation agreements with China and continue to explore strategically significant Chinese-backed infrastructure projects.

‘Most of the investment and financing that is taking place would still be happening without the BRI’, comments Xinyue Ma of Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center. ‘While BRI is adding a certain political significance in some of the cases, the impact is more symbolic than de facto.’

But this symbolic impact could translate into real opportunities, argues Antonio Riva Palacio Lavin, counsel at Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle. ‘At least in theory, BRI will mean that participating nations receive targeted funding for new projects. It also makes it much easier for the officers of Chinese entities to justify new projects. If the government is encouraging companies to seek out new markets that China hasn’t traditionally served it makes it more likely that sales teams will use that to justify a push into those markets.’

‘Part of the significance [of BRI] is that it is politically easier for Chinese companies to engage with a country that has received the backing of the state’, agrees David Blumental, a Hong Kong-based partner at Latham & Watkins. ‘That broad influence will continue to play its part, but if you look at it deal by deal it’s a different story. The bulk of these investments are taking place because they make solid economic sense for both parties. Politics really plays a subordinate role to economics here. The impact of this on businesses in Latin America should not be discounted either. It has definitely caught the interest of companies that want to enter the Chinese markets or to secure Chinese funding for their projects.’

Countries that have signed a Memorandum of understanding

Bolivia , Chile, Costa Rica, Panama, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela

Countries that have signed a document of cooperation or diplomatic relations

Cuba, Dominican Republic , Ecuador, El Salvador

A wave of purchases of overseas assets, particularly in the hospitality and entertainment sectors, led the Chinese leadership to put a brake on outbound investment. In part, this has been fuelled by a policy of keeping US dollar reserves stocked, though attempts to steer China’s economy toward domestic consumption have also played a big part. While this new policy has tightened the spending of SOEs and policy banks, it has not restricted private entities to the same extent. With Latin American markets opened by the first wave of investments, private entities have found it to be an attractive destination to invest.

Since 2000, state-owned companies accounted for 70% of all Chinese investments in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, the picture is changing rapidly. Foreign direct investment (FDI) from Chinese private entities looking to tap Latin America has risen from almost zero to over $100bn a year since 2005, with large sums targeted toward the acquisition of companies in the service sector.

The rise of private money tends to get overlooked, but it is the most important part of the story for China-LatAm relations. Partly this is because banks, law firms and other professional advisers have focused on SOEs as a source of revenue. ‘It’s not that they’re low-hanging fruit, but they are an attractive client’, says Antonio Riva Palacio Lavin, counsel at Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle. ‘When a firm is engaged by an SOE it has found a large, stable investor that will bring a lot of money to the region. But across the Latin America and Caribbean region there is a huge amount of private investment. Obviously, it depends how you define private, because in China there often isn’t such a clear line between state-owned and private business when you get to a certain size, but you have large banks in the Mexican market, you have airlines establishing direct flights from China to the region. There is a lot of investment going on. One of the very first things I did with a Chinese private company was to help them set up a joint venture in North West Mexico to import products from the US, finish them in Mexico and ship them to China. The trade links are much more numerous and complex than the SOEs and resources discourse that gets played out.’

‘The headline public deals that get you exposure when they close are great for publicity’, adds Nicole Pineda of Harneys, ‘but in the long term it’s the volume transactions we’re more interested in. The growth in private investments is a sign that Chinese interest in Latin America is healthy and stable for the long term.’

This rise of private money may also help to explain why the amount of investment appears to be falling. ‘There are fewer of the capital-intensive, state-backed megaprojects that formerly dominated the investment landscape, but there are in fact more investments taking place today, and these investments are coming from a wider variety of sources’, says Ma. ‘Alongside that, M&A is becoming the major type of investment as opposed to greenfield investment. More than 60% of the money that Latin America receives from China is in the form of M&A investments.’

Investments have not only diversified away from the traditional focus on raw materials. While just four countries – Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador and Argentina – have received over 90% of the loans Chinese entities have issued to Latin America in the last 15 years, those advising Chinese clients are seeing a broader geographical interest.

‘The appetite for Latin America is still high, but it is less concentrated in certain countries’, says Hogan Lovells’ Zaldivar. ‘Interest used to be focused on Venezuela and Brazil. Now we are seeing China is reaching out to other countries in the region and investing in places like the Dominican Republic and El Salvador. That is a really interesting change.’

The battle for Latin American trade

In a region that has been long seen as the United States’ backyard, China’s growing influence has led to inevitable political reactions. In 2018, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned Latin American nations to be wary of “predatory” lending by Chinese investors trapping countries in low-value chain raw material sales at the expense of building their manufacturing and services capabilities. Yet for many businesses in Latin America, the arrival of Chinese money could not have come at a better time.

The Trump administration has called for cuts in foreign aid to Latin American countries, a move that will likely push affected countries closer to China. The US has also withdrawn from the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade agreement which was set to boost its ties with Chile, Peru and Mexico, while calling for the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the US, Canada and Mexico.

‘Anecdotally, this is definitely a huge thing’, says Riva Palacio. ‘Even without looking at the hard numbers, anyone who works in this space can see that in a number of Latin American countries entrepreneurs and businesses are exploring markets beyond the US, and China is becoming increasingly attractive to them.’

Latin America is also becoming increasingly attractive to Chinese investors who face political pressure in more established markets. For example, Mexico is now working with Huawei to build out its telecoms infrastructure, while Australia and a number of European countries have faced pressure to find alternative suppliers.

‘The challenge for Chinese businesses is that markets like the US and EU are now attracting investment from other sources’, says David Blumental, a Hong Kong-based partner at Latham & Watkins. ‘At the same time, China has found it harder to acquire the things it really needs, particularly in the form of new technologies from the US. As a result of that double bind, Chinese companies are finding that the opportunity to expand into new markets across Africa and Latin America is increasingly attractive. They can sell products and acquire resources without facing the same political restrictions and competition from rival investors.’

However, says Miguel Zaldivar, it is a mistake to see China’s interest in Latin America as politically motivated. ‘I don’t see politics. What I see is Chinese companies that need to run their factories, export their goods and buy market share. If you look at the economic terms of the financings it is clear they are not subsidised. These are actually heavily negotiated transactions. And if you see the engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) agreements they are exactly like any other EPC contract. To call it politics is a distortion of the reality. Chinese investors have simply seen that there are great opportunities in Latin America, they have realised that they can compete in that market now and they are very, very aggressive and they are moving in.’

Paul Wee has worked on many of the largest outbound deals to come from China, including several in Latin America. The assumption that Chinese loans to Latin America are offered on favourable terms with political strings attached is, he says, fanciful.

‘The general assumption that financings from China Inc. come on favourable terms and with less stringent checks is a gross oversimplification that needs to be put into context. The cost of any loan will depend on the quality and source of the financing. As a renminbi financing often has a lower cost compared to a US financing, Chinese banks are likely to be a cheaper source of financing. A lot of assumptions get thrown around about Chinese loans being subsidised. Generally, they are not subsidised. From the Chinese banks’ perspective, the loans are offered at market rates. It’s just that the Chinese banks have a lower cost of funding in renminbi.’

The other prevailing assumption surrounds policy conditions. ‘Whenever you’re talking about a government borrower or a government-linked company the assumption is that China doesn’t impose any policy considerations. The facts are more or less right, but the interpretation placed on them – typically, that a policy-light approach is China’s attempt to exert influence or win new friends – is wrong. From China’s perspective it is perfectly natural to operate a non-interference policy. Even government borrowers do not have policy considerations imposed on them.’

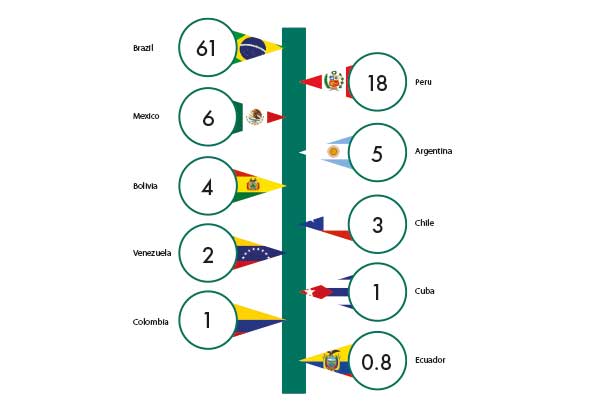

Chinese investment to Latin America by country (US$bn), 2003-2016

(Source: Bureau van Dijk, fDi Markets)

The popular wisdom overlooks the large number of exceptions that exist. ‘Even though Chinese institutions generally wish to avoid interfering in the domestic politics of borrowers, there are an equal number of Chinese financings out there that do not conform to that logic. If you’re talking about the covenants, security packages, requirements for guarantees or whatever needs to be put in place to ensure a loan gets repaid then, believe me, Chinese banks would not give an inch. They are very stringent when it comes to the security package and guarantees.’

While loans issued by Chinese development banks typically have higher interest rates than those issued by international development banks, they do not come with the same environmental, social and governance (ESG) restrictions, meaning they can be put to use more cheaply. However, the game is not without risk to either side.

China has begun to demand Venezuela repay some $20bn in debts and last year ended a “grace period” for debt relief. Ecuador, one of the smallest countries in Latin America, has been the third biggest recipient of loans. Deals struck under President Rafael Correa have seen nearly $20bn flow into the country. In return, 90% of Ecuador’s crude oil will be sent to China for the next five years. These examples sound a note of caution about the potential for political strings to come attached to these loans. Latin American countries have run up a trade deficit with China of more than $60bn, and with the political and economic indicators taking a plunge in a number of countries, their ability to repay these debts will tested to the extreme.

‘One interesting thing I am seeing is the breach of investment contracts by host-country governments’, says Lin Zhong. ‘These nations are in financial crisis and it has led to a breach of their commitments. Some countries in the region also impose a very high tax rate, which is de facto expropriation of our [Chinese] clients and has led to law suits there. We try to protect them through bilateral arrangements between the Chinese government and local counterparts, and also through certain dispute resolution mechanisms such as the investment dispute resolution centre at the World Bank, but the practice is becoming more prevalent.’

There are signs that Latin American countries may become more wary of Chinese money, but the trend for the coming year will be one of continued China to Latin America trade, says Xinyue Ma. ‘The last 12 months have seen greater trade flows between China and Latin America and this is consistent with the antagonisms of the Trump administration. Certainly, there is a greater opportunity for China and Latin America to trade and work together. Considering the macroeconomics of many Latin American economies is not very stable it is going to be a very important but not very stable area going forwards from the Chinese perspective.’

However, there are two sides to this relationship, and for China’s trade with Latin America to continue both sides will need to show willing, concludes Zaldivar. ‘There is a lot of political change in Latin America right now. They recognise the importance of China to their countries. But they are still in the learning stage. There’s a lot of talk but there has to be more action between the parties for the trade flows to continue. The Chinese position is quite stable, but it is a learning process by new governments in Latin America.’

The (new) rules of engagement

In 1964, the year Alibaba founder Jack Ma was born, China’s annual GDP was around $60bn, meaning the then most populous nation on earth’s economy was roughly the same size as Italy’s. That same year President Goulart of Brazil was overthrown in a coup d’état. It would have seemed unlikely to anyone born in this period that the two countries would become leading trade partners.

On both sides of the Pacific, entrepreneurs and business leaders who grew up expecting to sell their product to the US market are now having to play by a new set of rules that are yet to be fully defined. It will be left to the lawyers to work out exactly what they should look like.

‘One of the most significant developments I have seen in international trade is that a large number of companies are now having to find ways of establishing rules for how they can interact with each other’, says Antonio Riva Palacio Lavin, counsel at Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle.

‘Cattle growers in Mexico are selling meat in China, Chinese honey harvesters selling their product in Mexico. In a way, that is far more interesting in terms of the legal consequences than seeing a large SOE going into Latin America to build hydroelectric plant. Those larger projects are almost too big to fail. The numbers involved are so large that everyone has an interest in it going ahead. When the numbers are smaller there is less incentives for the banks, regulators and business leaders to make a project succeed. That’s when you start to find yourself challenged as a lawyer.’

The growing demand for China to Latin America cross-border work was one of the reasons Curtis established a presence in Beijing. With offices in Mexico City and Buenos Aires, the firm found itself needing to service both a growing number of Mexican and Argentinian clients wishing to do business in China, and a steadily increasing flow of Chinese clients operating in Mexico and Argentina. Riva Palacio, a Mexican national, spent five years acting as the firm’s chief representative in Beijing, helping to build its cross-border advisory practice. He says that while Chinese clients expect their firms to have an on-the-ground presence in international markets, they do not necessarily appreciate the complexities of operating in such a radically a different legal environment.

‘The biggest cultural barriers we have seen is that Chinese clients tend to place countries and their laws into very broad categories’, he comments. ‘From this perspective, the law is either US law, European law, or something less robust that will give them much more leverage or negotiating power. To generalise massively, there can be an assumption that from a legal perspective engagements with Latin America will be much more akin to Africa than Europe or the US, which is not accurate. Part of the process we have been through with our Chinese clients is to sit down with them and explain the features of each particular system of law, which aspects of that law would help them to enter a market, and what the limits of such law is for achieving their objectives. It is important to always make it clear that there is no homogeneous body of law and that national differences matter.’

Lost in Translation

In large part these challenges stem from a lack of familiarity between Chinese and Latin American parties. Trade may be picking up, but Latin America is very far from being China’s backyard.

There are still few direct flights from China to the continent, and Chinese businesses looking to Latin America will find that relative costs are higher and networks less well-established.

Latin America’s legal and business environments also remain somewhat mysterious to Chinese buyers.

‘Adapting to the Latin American market culturally is one of the bigger barriers to Chinese investment, and this is especially the case when it comes to appreciating differences in labour relations and legal and regulatory frameworks’, comments Xinyue Ma, China Research and Project Leader at the Global Development Policy Center at Boston University. ‘Historically, Chinese businesses have moved slowly in Latin America, learning how to operate in the market through trial and error. Recent history has shown that Chinese companies take a long time to adapt to the local regulatory and market environment.’

In particular, she says, dealing with environmental and social safeguards have traditionally been problematic for Chinese outbound investments, especially in Latin America where countries are more likely to have strong regulatory mechanisms in place, even if the execution and enforcement of those mechanisms is sometimes patchy. ‘Unlike multinational banks, Chinese development banks do not have such a rigorous mechanism or internal safeguards. They are not compelled to avoid certain types of investment or abide by certain environmental and social standards and processes.’

Jennifer Zhang, a partner with DeHeng Law Office in Beijing, says these issues date back to the early days of China’s enhanced engagement with the developing world. ‘What we learned in the 1990s is that Chinese banks are not familiar with a range of standards that are considered the norm elsewhere, whether that’s environmental standards, labour protection standards or any other form of non-financial commitment that comes with a typical development financing. It is not that the development banks or other financing institutions set out to deliberately violate these standards, it is simply that they were used to the Chinese way of financing and ran into problems. From that early experience development banks learned rapidly how to structure things in a way that meets the required standards relevant to the country in which they are investing, but some problems remain. Things like community protections remain relatively unfamiliar to Chinese lenders because they are rarely encountered at home.’

‘The rapidity with which Chinese businesses have matured in their approach to Latin America can be seen across the board.’

Even Chinese businesses that are well established in Latin America can find it difficult, adds Lin Zhong of EY Chen & Co. ‘Complying with local regulations in terms of visas, immigration and local labour law can be a challenge for Chinese parties and often requires additional legal support, especially if there is some kind of labour outsourcing arrangement.’

Analysis issued by The Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China (MOFCOM) in 2015 based on a detailed study of 254 companies involved in outbound investments showed that failure to manage labour relations was the biggest hindrance to Chinese investments in the Latin America, followed by issues arising from failure to understand political and regulatory structures.

Examples of Chinese-backed projects being derailed due to concerns over their broader social impacts are numerous. The Rosita hydroelectric project in Bolivia, agreed in 2016 with backing from China Three Gorges Corporation, has been placed on hold due to insufficient prior consultation with indigenous communities likely to be affected by the project, while two Chinese-financed dam projects in Santa Cruz, Argentina were suspended by the Argentine Supreme Court in 2016 pending environmental impact assessments on the proposed sites.

But it is not only the Chinese side that needs to be educated. ‘While the number of lawyers relative to the population is high In most Latin American countries, there are elements of local legal practice that have comes as a surprise’, says Charles Wu of Zhong Lun.

‘To take one example, the notarisation process is very burdensome for signing public deeds in many Latin American countries. To complete the process you must appoint a time to go to the notary office with an approved notary officer; signing in the presence of a witness is not taken as sufficient proof that the document was approved by the signatory. Company officials are often told that there is legal requirement to be physically present in the country to transact business while at the same time being refused visas. Such formalities do not make business easy. It is also the case that, even on some major projects where the counterparty is a Latin American government, key documents will only be made available in Spanish.

Further, it can be difficult to persuade the local party, particularly if they are government or state-owned entities, to agree to international standard arbitration. They will insist on either the arbitration chamber in their home country or, for private parties, they will perhaps consent to having a hearing in Miami but no further afield. Hong Kong, London, Singapore – they won’t accept any of those.’

But as Zhang points out: ‘Latin American lawyers need to understand that Chinese investors have their own system for outbound investment. If you are looking for Chinese capital it seems only reasonable to accept that it will come with characteristics that are familiar to Chinese lenders.’

It is also clear that Chinese entities are becoming much more adept at executing cross-border investments. Miguel Flaksman is executive managing director at Brazil-based Banco BOCOM, which since 2015 has been majority owned by China’s Bank of Communications. He says a new generation is showing that the old adages no longer apply.

‘Business people and entrepreneurs coming from China are adapting to local market conditions at a much faster rate. At the same time, they are really making an effort to learn how to do business in those markets. They have experience of a range of jurisdictions and know that not everything works the same way. You can definitely see that the younger breed of investors is far more exposed to a variety of standards. The do not experience the cultural misunderstandings that had traditionally led to problems.’

Latham & Watkins’ David Blumental has been doing outbound work for Chinese clients since 1998 and agrees that the level of sophistication among Chinese clients has increased significantly. ‘Not only are Chinese business teams much more familiar with international approaches to doing deals, but their expectations of external counsel are now significantly higher. It is now common to be engaged by a Chinese company with a large in-house team containing a lot of very well-qualified lawyers who are familiar with international legal structures.’

In-house teams at Chinese companies are also becoming more demanding, notes Molly Su, a finance partner with King & Wood Mallesons. ‘Chinese clients are more sophisticated and are asking for more from their counsel. They have their finance team with international education background, they know about the international documentation. The ability for an SOE to negotiate is getting much better than before, and the expectations they place on external counsel are much higher than before. Leading firms in China have to be up there with the best practices globally.’

There has also been a pressure to cut costs, adds Lily Zhang of Harneys. ‘Recently I attended a dinner with a famous Chinese investment group that has a lot of active outbound investment deals. Their legal team told me that they are more and more concerned about the cost of engaging outside counsel in the context of outbound investment deals, and that in-house counsel will now do a lot of the work to remove these costs.’

The rapidity with which Chinese businesses have matured in their approach to Latin America can be seen across the board, from the role of in-house counsel to the quality of the underlying documentation used in financings. DeHeng’s Jennifer Zhang regularly advises Chinese commercial banks and financial institutions, including China Development Bank and Exim bank, in their lending to Latin America. There has been a trend, she says, of running financings under international standards and with a higher degree of security demanded.

‘From the outside these transactions can look very simple but the loans typically rely on a parent guarantee. If the parent company becomes insolvent the Chinese bank has no recourse to recover assets. If the borrower is an SOE then it is relatively simple to secure parent guarantees, but if it is a private company then it is not so simple, particularly when the company wishes to invest in Latin America.’

Molly Su has seen similar developments in the approach taken by major policy banks. ‘Ten years ago policy banks provided finance based solely on guarantees from the SOE that was preparing to undertake the project. The bank tried to wrap up the transaction very quickly on a simple structure and was certainly not willing to fly to Latin America to do outside due diligence. Now they are becoming much more internationalized in their approach. They may require local assets as security or use English-law governed documents to underwrite the loan.’

A further development, says Paul Wee of Norton Rose Fulbright, is that Chinese banks are participating in syndicates and co-financings rather than accepting all the risk a project in Latin America entails.

‘More and more I am seeing Chinese banks not wanting to go it alone when it comes to financing big, sizable projects. There is a concerted effort to make it a co-financing, not just with other Chinese banks but with international banks and financial institutions.’

An increase in trade is inevitably followed by an increase in disputes. Lawyers active in the cross-border space are seeing a big growth in arbitrations at the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC), including significant cases concerning countervailing duties and anti-dumping. ‘There are far more disputes involving Chinese and Latin American parties than gets reported, simply because of the nature of the process’, says Xinyue Ma.

It is a trend we can expect to see continue as international trade becomes weaponised, forcing both Chinese and Latin American parties look for new markets. Riva Palacio highlights one of the more interesting unintended consequence of this political tension.

‘As the US ceases to be the single easiest and most attractive market for Chinese manufacturers they are shifting their products elsewhere. Chinese products that did not previously flood European or Latin American markets are now starting to do so, and that is causing frictions in Europe, Japan, Korea and a number of Latin American jurisdictions. These jurisdictions, and specifically Latin American jurisdictions, are starting to ramp up their countervailing duty investigations, their anti-dumping investigations against Chinese products. That comes with an increase in work not just with defending these companies against these investigations but in helping them plan for those investigations and for a new reality where they will be facing this kind of scrutiny that they didn’t necessarily have to face before. It is the start of a new world and the legal outcomes are still unknown’.

Getting the right advice

Anecdotally, Chinese interest in the continent continues to grow. Of the more than 50 China-based lawyers specialising in Latin America consulted for this report, over half said they had seen a growing demand from Chinese clients wishing to invest in Latin America over the past 12 months.

Whether there will be enough lawyers to satisfy this demand remains a moot point.

‘Doing business in Latin America can be very niche and very complicated’, says Susan Guo, a partner at AllBright Law Offices in Beijing. ‘It requires a lot of hard work to assemble teams with expertise on the ground and it is difficult to get people who tick all of the cultural, linguistic and subject matter boxes in a single market. When suddenly a matter crosses several borders it becomes exponentially more difficult. If you layer on a Latin America-based component to the deal then you really are looking at a very small sub-set of people who are qualified to handle it.’

Miguel Zaldivar, regional chief executive for Asia Pacific and Middle East at Hogan Lovells, has a similar take. ‘Sophisticated Chinese buyers of services are looking for those that understand their culture, can deliver the product in English, and can negotiate in Spanish. It is a highly, highly specialised end of the market and there are very few true players. The simple reality is that when most firms work on a matter in Latin America they advise the Chinese client then refer the work to a local firm in the relevant jurisdiction. It is often not even possible to have the deal written under local law because when it comes to financing the banks will require documentation that is not dissimilar to what you see in more mature markets. You have to have the right guarantees, reps and warranties, and if you look at the deals that are actually placed you will see that all the documentation is governed by English law or New York law.’

There may be a small number of lawyers and firms that are truly able to handle such work, but client demand means many will advertise their ability to do so.

‘Clients do care about where a firm has offices and they do prefer to see firms with a presence in the markets they are looking to access’, says David Blumenthal of Latham & Watkins. ‘That doesn’t always make sense – if you have an office in Sao Paolo it is completely irrelevant if you are doing a deal in any country other than Brazil – but the fact is clients care and that will drive more firms to formalise their China to LatAm offering.’

Monica Sun, a partner with Herbert Smith Freehills’ Beijing office, agrees. ‘My observation is that Chinese clients generally prefer to work with firm that have an office the jurisdiction they wish to operate in, and a firm is certainly seen as much more competent to handle matters in a market if it has also a physical presence there. This becomes a driver for Chinese firms to open offices overseas, which is one of the reasons why we are seeing Chinese firms go abroad now. Clients need to know that having a small office in a jurisdiction doesn’t necessarily make you more able to resource a matter in that jurisdiction. I believe that partnering with the best local firms to drive a matter is the best way to proceed.’

Our survey of China/LatAm specialist counsel shows…